How Nonfiction Writing and Documentary Filmmaking Curate the Truth

Chachi D. Hauser on Constructed Realities in Literature and Film

All of my writing life I’ve written nonfiction. I don’t know if this is simply due to the coincidence that the first writing course I was accepted into in college was beginners CNF. In that class, however, as I learned more about the genre—once I broke out of my initial understanding of nonfiction as meaning memoir and saw how it could be at once poetic, lyrical, personal, analytical, and philosophical—I came to love it.

For me, nonfiction is a genre that is excitingly malleable, open to experimentation. I soon came to revere writers like Maggie Nelson, Gloria Anzaldúa, T. Fleischmann, and more recently Lars Horn, who work to further challenge the boundaries of the genre’s definition. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that all of these writers, like me, also hope to challenge definitions of gender; I often think of nonfiction as a nonbinary genre.

For the past seven years I’ve also worked in documentary film, first as a researcher and later as a producer. In my nonfiction writing, I’ve taken much inspiration from the process of documentary editing. An editor’s first step on a new documentary is to watch all of the hours of footage, which can often extend into the hundreds. During this initial viewing, the editor will usually take notes and eliminate parts that are definitively not in the film—for example, when the cameraperson is moving the camera around, setting up the frame—in order to get the footage down to a more workable state.

Usually, after this “first pass,” the editor will watch the footage again (and again), cutting it down further, eventually shifting to focus on individual scenes with their own contained narratives. No matter their workflow, the editor is always looking to find the connections that stand out in the footage. Through all of these viewings, they are looking to identify and reinforce the film’s dominant themes, continuously changing the order of scenes in a game of Tetris to uncover links between the footage previously unnoticed by the director during the actual filming.

In writing my first book, I thought of everything I’d lived as those many hours of footage—I culled through these experiences, looking for thematic connections between them, without paying much attention to the linear relation of events. In her craft book Meander, Spiral, Explode, Jane Alison writes about how, as we read printed words, we “hear” them internally, registering the sound of the word. But first, before we hear the word, we see it—we create an image in our mind associated with what we’ve read. Reading and writing are highly visual activities and, like film editors, writers control what readers see.

Writers, too, take advantage of the cinematic “Kuleshov effect,” creating meaning through the juxtaposition of images or sequences. For example, in my book, I hoped to create a comparison between two locations that are very significant to me, New Orleans, where I’ve lived most of my adult life, and Disney World, where I spent many memorable moments of my childhood, having grown up in the Disney family. By writing repeatedly about how both New Orleans and Disney World were both built on top of swamps, I wished to visualize how, for the sake of monetary gain, some humans have preferred a constructed fantasy over the wild beauty of nature—through further “editing,” I also wished to connect this mentality to my own romantic relationships and how we culturally view love.

Reading and writing are highly visual activities and, like film editors, writers control what readers see.

As I toyed with various juxtapositions of scenes from my life, I began struggling with its genre. While nonfiction is a genre that claims to present the “truth,” I know from writing my book—which I’ve had trouble defining, as it might be called a series of linked essays or a memoir, though sometimes I wish I could’ve called it a poem—how much a writer can cut/edit/shape their story until they themselves are a character. At times I’ve questioned the importance of having to categorize writing by a name at all. Why can’t we, as other cultures seem more willing to do (take Annie Ernaux’s oeuvre, for example), simply call something “a book” and leave it at that? But ultimately, I know the answer to this has to do with that horrible word: marketability.

Like documentary film, I think of creative nonfiction as being different from journalism; but, of course, the choice of how much one can stretch their artistic license is up to the individual. I have witnessed the more questionable lengths that directors and editors go to in order to locate the truth while also manipulating it—for example, through the use of “frankenbiting,” cutting together the disparate words of a speaker in an interview so that their sentences are more “streamlined.” (This technique was apparently used for the famous final sequence of The Jinx, when Robert Durst seems to admit to murder whilst speaking to himself aloud on a hot mic.)

Though I usually relish this blurriness, at times this categorization of nonfiction scares me, as if I have any authority over the truth. This fear came to a head when my book was published this past spring. When you’ve never experienced something before, how are you supposed to anticipate it? Like pining for my first kiss or the seemingly interminable countdown to losing my virginity, the longing to publish my first book was perhaps misplaced—a longing for a totally unknowable sensation, relying only on the accounts of others to believe I should long for it in the first place. When it finally happened, I didn’t feel particularly prideful, validated, happy, or whatever else one might expect; instead, I felt a much messier set of emotions I’m still working to make sense of.

Friends, family members, and ex-lovers I’d mentioned in the book (with aliases) started popping up, sharing their reactions with me. “Characters” told me how surreal it was to see themselves in this way, like watching the scenes of their lives in a movie, the camera distinctly angled from my perspective. The reviews were punctuated by a single devastating one. I wondered, briefly and in vain, if it would’ve been possible to have written or published the book as fiction, as a matter of protection for myself and the people I’d written about. It was, after all, a construction—since I’d always thought of it this way, I hadn’t fully understood how it might be received otherwise, as “reality,” and thus have real consequences.

At the same time, when my book came out, something else happened: people began coming to me with confessions. Stories poured out of people. After readings and drunkenly at parties. Through texts and emails. I’ve been approached by friends and strangers alike with these confessions because, in witnessing my honesty on the page, they feel it’s only fair they share some of their intimacy with me in return.

In exposing the depths of my shame, my desire, my joys and failings in love, I’ve become a receptacle for the heartbreak of others. And, in this act of collection, I have found something out: my whole world is heartbroken. To love is to offer one’s heart up and to know that, in some way, somehow, it will not remain whole. Still so many of us do it, offer ourselves up, we need it, otherwise how will we know we have a heart at all? I have not spoken this much about love before in my life.

To learn this, and to arrive in these newly intimate connections in the wake of the book’s publication, has given me great solace. I am not alone; we are not alone. Despite my initial hang-ups, I have come to be thankful that I didn’t try to publish the book as fiction. I’ve remembered that the true gift of engaging with a work of nonfiction, or documentary, is to connect with other people’s lived experiences, to even see yourself in them, and to be reminded of the vastness of what we share.

__________________________________

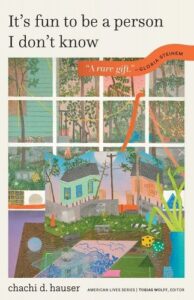

It’s Fun to Be a Person I Don’t Know by Chachi D. Hauser is available from University of Nebraska Press.

Chachi D. Hauser

Chachi D. Hauser is a filmmaker and writer. Her essays have appeared in Hobart, Prairie Schooner, Third Coast, Crazyhorse, and the Writer’s Chronicle. She lives in Paris.