How Nigeria’s Ideological and Ethnic Map Reflects Its Enduring Divides

Emmanuel Iduma on the Origins of the Nigerian Civil War

A video, recorded on May 26, 1967, begins with a noiseless pan of faces: mostly men who are gathered, it seems, in front of the State House in Enugu, the capital of Nigeria’s Eastern Region. They’re holding up large proclamations.

GIVE US BIAFRA, FEDERATION HAS DIED

BLESSED BE THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF BIAFRA

DECLARE US BIAFRANS NOW

BIAFRA WE WANT

Each man has assumed the demeanor he considers most momentous, as if readying for a snapshot—fists are raised, eyes are shaded with sunglasses, faces are held in fixed smiles. Then the camera shows another placard, which partly reads OJUKWU. Then it cuts to different footage.

We’re inside the State House now. More men, a scattering of women, gathered for a meeting of the Consultative Assembly of Chiefs and Elders—a group, by some estimates, of up to 335 people. They flank a dais. From the rear, Odumegwu Ojukwu emerges, walking with his hands folded behind him, and turns to the camera just when he is closest to it. He is young enough for his stern-faced glance to seem as though he is working up resolve.

“Your meeting today is very crucial,” he says when he’s at the podium. “Eastern Nigeria is at the crossroads. Since our last meeting, everything possible has been done by enemies of the East to escalate the crisis in an attempt to bring about the collapse of this region. They have failed and will continue to fail.”

I was going to Afikpo without the illusion that my ancestry was remote.

I watch the balance in the lieutenant colonel’s demeanor, the care in his enunciation, the bulge of his eyes, the movement of his brow. I consider him the type of man who understands the distinction between authority and adoration, and who can leverage the former to enjoy the latter

The next afternoon, following a noisy session, the Consultative Assembly, made up of several leading politicians in eastern Nigeria, unanimously mandated Ojukwu to declare the region an independent state at the earliest practicable date. Its name and title would be the Republic of Biafra. Three days later, during the early hours of May 30, Ojukwu gathered diplomats and journalists to the State House and made a declaration of independence.

Then, on June 3, 1967, a soundless video montage is recorded by the Reuters news agency: The Biafran flag hangs at the entrance to the State House, now being called Biafra Lodge. A huddle of men in suits, each awaits his turn to shake hands with Ojukwu. Ojukwu, in a striped, dark kaftan, is addressing the press. He looks up half smiling and now, seen closer, brings a cigarette to his mouth, his eyes closed as he takes a puff. A poster—DON’T SELL YOUR REGION, it reads—is affixed to a window, with the illustration of a soldier in uniform holding out a pouch marked with a £ sign. Close to the end of the video, a smiling man, wearing sunglasses and a bowler hat, holds a drawing of Ojukwu below his chin.

The rest of the seventy-second video contains footage of the Niger Bridge in Onitsha, the town at Biafra’s western border: Soldiers have mounted a barricade. A group pushing a cart with a jumble of belongings, including a bicycle, walks across in a hurry, barefoot. One woman is running. Behind her, three armored tanks are parked, squat and malevolent.

*

I set out first to Afikpo, the town in northeastern Igboland where my family is from. It was a trip planned with little preparation, during my first month of being back in Nigeria. I kept most of the luggage I’d returned with in Ayobami’s flat. Yet while settling into my leased apartment and having some time to spare, I wished to know all that was known in Afikpo about my uncle. I hoped to pick up fragments of his life story from my father’s relatives, who were likely to welcome me once I mentioned my father’s name.

I say that I am Igbo, and my people are from Afikpo, yet I confess that, due to how often we moved as a family, I am estranged from this town and that ethnicity. I have never lived here, only visiting when prompted by an occasion in the family.

Yet at twenty-two, right after university, I went unaccompanied for the first time. I stayed in the house of my father’s close friend, who was the secretary of one of the traditional councils and had reams of unpublished historical accounts in a back room. I spent idle hours hunched over piles of paper, realizing that I felt inclined to study Afikpo’s past more than its present, as though my chief method of belonging to the town was historical, not filial. This time, I was going to Afikpo without the illusion that my ancestry was remote.

*

There is no pan-Igbo origin story. Unlike the Yorubas, for example, who claim universal descent from Oduduwa, the various subgroups in Igboland—a tropical forest region with a total landmass of about forty thousand square kilometers and an approximate population today of forty million—are not linked by a common ancestor or a linear narrative of settlement. Yet the word now standardized as Igbo—once written as Eboe and Ibo—has been in use since at least 1789, when Oluadah Equiano, perhaps the best-known precolonial Igbo man, who was sold as a slave to a Royal Navy officer, published his autobiography.

Scholars take two approaches in determining a shared cultural identity for Igbos. First, an etymological approach: that Igbo is a word for ancient inhabitants of a forest area or for a community with shared values. Others focus on the geography of the area by examining settlement patterns and arguing that there was a core heartland from which subgroups originated.

The journey into Biafra must cover a patch of speculative, ideological territory.

There were two known attempts to found empires within Igboland, and thus create a unified political system among the Igbos. The earlier Nri empire was less politically savvy. Founded during the course of an agricultural revolution in the fertile valley of the Anambra River, it concentrated its efforts on extracting tributes and perpetuating control through rituals, eventually failing to perfect a system of profit-yielding capital required of all modern empires. The latter Aro empire, whose rise coincided with the decline of the Nri, lasting from 1650 to 1900 and based in Arochukwu, combined an aggressive policy of trading in slaves with a mercenary army to control independent communities in the area.

Beginning in the early 1900s, after a British-led expedition destabilized the Aro network of trading and patronage, pan-Igbo identity began to take shape under the rubric of an emerging pan-Nigerian one. Then came Biafra. The Eastern Region, from which Biafra was formed, included a panoply of ethnic groups. Hence it is incorrect to assume that the conflict, strictly speaking, was an Igbo one. It is not a stretch, however, to argue that in the aftermath of war—and since the final battles were fought in their shrinking heartland—the Igbos felt, and continue to feel, the vanquishment more acutely. This is why the current agitators for Biafra are often called Igbo nationalists.

The meaning of Biafra is unclear, but it began to appear on European maps in the sixteenth century. In the centuries before interior exploration by Europeans began, Biafra—sometimes spelled Biafara or Biafar—was as imprecise a location as any utopia. In the Lopes-Pigafetta map, published in 1591, it was thought to be in today’s northeastern Nigeria, near Adamawa.

In Willem Bosman’s 1705 map, it was found in the grasslands of Cameroon, occupying all the areas south of the Cameroon River. Other cartographers denoted it in regions off the coast in the Central African Republic and Congo-Brazzaville. One located it north of that river, within the space of Nigeria’s breakaway republic.

I consider all those maps useful. The journey into Biafra must cover a patch of speculative, ideological territory. The war was just one of several attempts to name a place Biafra, only this time as a nation with fixed borders.

__________________________________

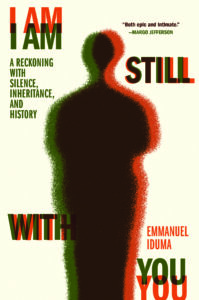

Excerpted from I Am Still with You: A Reckoning with Silence, Inheritance, and History by Emmanuel Iduma. Copyright © 2023. Available from Algonquin Books.

Emmanuel Iduma

Emmanuel Iduma, born in 1989, is a writer who trained as a lawyer in Nigeria. He is the author of the travelogue A Stranger’s Pose (Cassava Republic Press, 2018), which was longlisted for 2019 Ondaatje Prize. He has written for Granta, n+1, the New York Review of Books,BOMB, Brooklyn Rail, Aperture, Guernica, and others, and received many grants and awards, including the Windham-Campbell Prize. Iduma has an MFA in Art Writing from the School of Visual Arts, New York City and taught there for several years before moving to Lagos, Nigeria.