How New York City’s Radical Social Movements Gave Rise to Hip-Hop

Dean Van Nguyen on the Revolutionary History Behind One of America’s Main Musical Exports

Lincoln Hospital, Mott Haven, the Bronx. Like many medical centers that serve America’s sprawling metropolises, this striking redbrick building is a sad temple in hip-hop history. On August 27, 1987, DJ Scott La Rock, producer and co-founder of Boogie Down Productions, died on an operating table after being shot while riding in a Jeep through the Highbridge Gardens project. The loss of La Rock has been called hip-hop’s first tragedy.

Having opened its doors in 1975, the hospital was a relatively new building that replaced the old Lincoln Hospital, a pitiful, bloodstained, cockroach-infested construction known throughout the South Bronx as “the Butcher Shop.” It was in this old iteration of the institution that, in 1970, a group of radicals from both the Black Panther Party and the Young Lords founded Lincoln Detox. In an old nurses’ residence on the sixth floor, under posters of Angela Davis, Malcolm X, and Chairman Mao, “the People’s Program” offered holistic drug rehabilitation that included acupuncture, community service, and Marxist education classes, so participants could learn about their addiction through a communist lens. Dope was framed as chemical warfare that placated minority communities, revolutionary communism taught as the cure. Lincoln Detox’s director of political education was Mutulu Shakur, a committed revolutionary who would keep company with Afeni Shakur during the period and become stepfather to her young son, Tupac.

To tell the story of Tupac Shakur, hip-hop’s greatest radical, we must consider the radical origins of hip-hop.

About two and a half miles north of the new Lincoln Hospital you will find the cradle of hip-hop. Rarely is it possible to pinpoint the genesis of a culture to an address and moment, but on August 11, 1973, at 1520 Sedgwick Avenue in the Morris Heights neighborhood, DJ Kool Herc unveiled his two turntables and mixer at a back-to-school party in the building’s rec center. His new technique used a couple of copies of the same record to extend the instrumental break as friend Coke La Rock (no relation to Scott) jumped on the mic to work up the crowd. And with that, hip-hop was born. From these humble origins would grow a global behemoth, one of America’s two biggest cultural achievements, alongside jazz.

Hip-hop created billionaires but was born in poverty. It was a youth movement that began with zero mainstream interest and few commercial concerns. Nascent emcees loved to rap about two things above all else: partying and how good they were at rapping. But a lot of them sounded off about the struggle too, penning lyrics that wouldn’t have looked out of place in the Black Panther newspaper once hawked by the party’s rank-and-file members. From the earliest recordings, rap and radical politics intertwined. The music became a soapbox for the marginalized and oppressed to deliver dispatches from the urban decay they lived in. To tell the story of Tupac Shakur, hip-hop’s greatest radical, we must consider the radical origins of hip-hop.

*

It had to happen in the beautiful Bronx, a fiefdom of socialist thought, Marxist organization, and anti-establishment resistance since long before the Panthers or Young Lords showed up. When the Bolsheviks seized power in Russia in the October Revolution of 1917, New York’s Red faction toasted the news. They were not an insignificant pocket of the city’s population—Riga-born socialist leader Morris Hillquit ran for mayor that same year and won more than a fifth of the votes cast. The Communist Party USA was established in the city soon after, its membership mostly made up of poor Jewish immigrants who’d come off boats through Ellis Island. As late as 1931, four-fifths of the communists living in the city were foreign-born.

For these leftist dreamers, the Bronx was a particularly blessed domain. Consider the United Workers Cooperatives between Allerton and Arnow Avenues, on the east side of the Bronx, known to its residents as the Coops. In the mid-1920s, thousands of immigrant Jewish garment workers pooled their resources to build two cooperatively owned and run five-story complexes comprising 750 apartments. The Coops was a self-contained world of utopian ideals of a fair and equitable society. There were no evictions or rent hikes. Children enjoyed gardens and play areas, while a kindergarten provided hot meals. Adults attended communist meetings and engaged in Marxist-Leninist discussion.

Righteous slogans echoed throughout the buildings: “Wages up! Hours down!” “Make New York a union town,” “Black and white unite and fight,” and “Free the Scottsboro Boys,” a reference to the wrongful conviction of nine Black teenagers on charges of rape in Alabama who after years of legal wrangling would eventually all be pardoned. Residents of the Coops believed they were sitting in a relative paradise and watching capitalism’s end days, with communism ready to fill the void. As Vivian Gornick wrote in her 1977 oral history The Romance of American Communism, “There are a few thousand people wandering around America today who became Communists because they were raised in the Co-Operative Houses on Allerton Avenue in the Bronx.”

With the cold wind of the Depression blowing through America in the early 1930s, the Soviet Union began to be viewed as a more intriguing proposition. Americans soon wondered if communism could be a desirable alternative to the cruel irrationality of a capitalist system and the hunger, misery, and unemployment inflicted by its failings. Before McCarthyism made such an achievement practically impossible, a New York communist, Benjamin Davis Jr., represented Harlem on the New York City Council from 1943 to 1949, succeeding prominent civil rights leader Adam Clayton Powell Jr. But as the Red Scare took hold, Davis’s politics earned him a conviction for violating the Smith Act, a law that criminalized any action that was seen as advocating an overthrow of the government, and he spent five years in prison.

Membership of Communist Party USA eventually dwindled. Nikita Khrushchev’s “secret speech” in 1956 revealed more about the crimes of Joseph Stalin than had been previously known, and it shattered many members’ confidence in a socialist future. Still, uptown and the Bronx remained a hive of leftist action. The members of the Nation of Islam were no socialists, but Malcolm X respected the anti-racism activism of the Communist Party. After splitting with the NOI, his sermons often veered anti-capitalist as he saw capitalism and racism as bedfellows. “You can’t operate a capitalistic system unless you are vulturistic; you have to have someone else’s blood to suck to be a capitalist,” acknowledged the minister. The Black Panthers’ New York outposts were full of grieving Malcolmites who funneled his teachings into their overtly Marxist curriculum.

The Panthers operated in a very different Bronx than the ones the Coops’ founders knew. The 1950s saw the middle-class residents begin to flood out of the borough, drawn to the burgeoning utopianism of the American suburb. The Bronx went from two thirds white in 1950 to two-thirds Black and Hispanic in 1960-a process known as “white flight.” New York never fell to Jim Crow laws, yet there was an undeniable air of segregation. “Black kids didn’t play on white blocks; white teens didn’t walk through the projects,” wrote Panther 21 member Jamal Joseph, who grew up in Edenwald Houses, a project built in the 1950s in the Eastchester and Laconia neighborhoods that were once predominantly Irish and Italian working class. “Maybe we weren’t being fire-hosed, clubbed, and bitten by German shepherds like the Negroes in the South we saw on TV, but white storekeepers would kick us out, white teenagers would jump us, and white cops would beat the shit out of us for being in the wrong place at the wrong time.”

Devastated by the loss of hundreds of thousands of manufacturing jobs over the previous decades, blighted by heroin, and with insufficient public services, the South Bronx was fertile soil for grassroots left-wing activism. Some of it took on particularly assertive forms. In the early morning of July 14, 1970, members of the Young Lords entered Lincoln Hospital. With baseball bats and nunchakus, the activists gained control of the hospital within ten minutes. Cleo Silvers, a young Black member of the group, ordered administrators to leave the building. A Puerto Rican flag flew from the roof and signs hung from its windows read “Welcome to the people’s hospital” and “Bienvenidos al hospital del pueblo.”

The protest didn’t occur in a vacuum. For years, New York’s Black and brown neighborhoods had access to healthcare facilities of a disproportionately poor standard compared to those serving white New Yorkers. To draw on just one statistic, in 1952, the tuberculosis mortality rate in the Central Harlem Health District was nearly fifteen times the rate for nearby, mostly white, Flushing, Queens. To the Young Lords, the situation was intolerable, and so its primary concern was drawing attention to detrimental health conditions in their poverty-stricken neighborhoods. The group allied with the Health Revolutionary Unity Movement (HRUM), an organization of hospital workers who felt the established union was corrupt. A precursor to the hospital insurrection took place a month earlier, when the Young Lords seized a mobile chest X-ray unit used to seek out cases of tuberculosis and drove it from 116th Street and Lexington Avenue to a site in East Harlem.

But the takeover of Lincoln Hospital was a level up. The early morning storming was the beginning of what became a twelve-hour long occupation in protest of the hospital’s poor care conditions. With the disruption of potentially lifesaving work going on in the hospital, the execution had to be smooth and precise. “It took us a couple of months to complete the full planning of it,” Silvers explained.

In a press conference, the Young Lords listed seven demands, including funds for a new hospital building, increased minimum wage for all workers, and a day care center for patients and staff. The city would give no public guarantee that it would meet their requests. Feeling they’d made their point, and wary of the police lining up outside the building, the protesters crafted an escape plan. They donned hospital clothing and exited the building alongside other workers. Only two members, Pablo Yoruba Guzman and Louis Alvarez Perez, were arrested for possession of dangerous weapons—charges that were later dismissed.

That November, the Young Lords returned, with permission, to the halls of their great protest, to establish Lincoln Detox. With one in five people in Mott Haven battling addiction at the time, lines would start forming at the clinic at seven A.M., two hours before it opened. A lack of financial support meant that for the first eight months of the endeavor, everyone worked for free. Lincoln Detox eventually received city funding, and by 1971 it was detoxing six hundred people every ten days. Some participated in the clinic’s political education program, where lessons involved reading and discussing former Panther 21 member Michael “Cetewayo” Tabor’s pamphlet Capitalism Plus Dope Equals Genocide and Mao’s Little Red Book.

This union of Black and Puerto Rican communities for revolutionary struggle in the late 1960s and early ’70s was a crucial precursor to the grassroots creative expression that would take place.

As a staff member, Jennifer Dohrn—an associate of the Weather Underground through her sister, Bernardine, as well as the partner of Young Lords co-founder and key Lincoln Detox figure Mickey Melendez, with whom she had three children—would see patients rendered homeless by their addiction arrive at Lincoln Detox desperate and without hope. Once in its care, the clinic would try to explain to addicts why this horror was happening to them. Structure would be introduced into patients’ lives by allowing them to help out with a breakfast program, school program, or tuberculosis testing van.

“To watch people coming off of heroin and suddenly having this moment of feeling that their life was not controlled by it and they could contribute in a very different way to being part of rebuilding their community was a very hopeful time,” said Dohrn. “There was so much going on that you could suddenly define yourself in a different way as contributing as opposed to feeling useless and a burden.”

It was during the lifespan of Lincoln Detox that a new culture swept the borough, fusing the youths from diverse backgrounds into a rainbow coalition of baggy tracksuits and fresh sneakers. Together, African Americans, Afro Caribbeans, and Latino youth fostered hip-hop. For Silvers, both an ex-Panther and Young Lord, this union of Black and Puerto Rican communities for revolutionary struggle in the late 1960s and early ’70s was a crucial precursor to the grassroots creative expression that would take place in the same streets.

“It happened because of the struggle to unite African Americans and Puerto Ricans in the South Bronx,” she said. “That form of music, that genre of music, arose out of that relationship and that relationship started when the Black Panther Party and the Young Lords came together and started working together in the South Bronx. There was a definite rift between the two groups of people who were fighting over a tiny amount of jobs and anti-poverty funding that was coming in. And there was unity between the Black Panther Party and the Young Lords and the struggle to bring the community together to unite, which was the basis for the further development of hip-hop. Yes, that’s how it started. Black Panther Party and Young Lords again, we did a lot of work in the South Bronx and Harlem, and all around New York City.”

Jamal Joseph saw hip-hop as a descendant of the Black spoken word artists who directly preceded it. “Those poets were revolutionaries,” he said. “That’s what they talked about. If you looked at the Last Poets, Sonia Sanchez, and Amiri Baraka, they had beats behind them. They were always people laying down African rhythms on the conga drums. Sonia Sanchez started performing with jazz ensembles and combining what she did as a poet and just using her voice and her phrasing as an instrument. So, when hip hop came about, I saw it as kind of the next level, and that instead of the live beats, people were sampling records and cutting and scratching. But if you looked at what people were talking about, they weren’t talking about money, power, and fame. They were talking about police brutality and violence and poverty and how you overcame that. And Tupac came and really infused revolutionary consciousness in that. He started using the words revolution and liberation and struggle.”

__________________________________

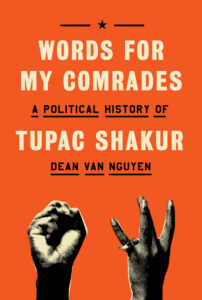

From Words for My Comrades: A Political History of Tupac Shakur by Dean Van Nguyen. Reprinted by permission of Doubleday, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2025 by Dean Van Nguyen.

Dean Van Nguyen

Dean Van Nguyen is a music journalist and cultural critic for Pitchfork, The Guardian, Bandcamp Daily, and Jacobin, among others. He is based in Dublin, Ireland.