How Nellie Y. McKay Forged a Path for the Study of African American Literature

Shanna Greene Benjamin on the Broader Narrative of

Black Women’s Intellectualism

African American literature, as a discipline, was never a promise. It was a hope fulfilled by scholars who fought to create disciplinary space for the furious flowering of a literature wrought by persons of African descent.

Nellie Y. McKay was one of those scholars.

Born in 1930, shaped by her Caribbean roots, and encouraged on to college by a church community that saw promise in this working-class single mother of two, McKay’s life captures the stakes of field formation while documenting the strategies Black women employ to live out dreams that transcend the low ceilings others put on their aspirations because of race and gender bias. McKay is best known for co-editing the groundbreaking Norton Anthology of African American Literature with Henry Louis Gates, Jr., but her impact on higher education is unknown by most of the general public and underrecognized by many in the professoriate. Even though establishing African American literature as a field, as a discipline unto itself, was a major part of her intellectual project, for McKay there was more to Black literature than “the guys.” “We’ve been trained to read and criticize Faulkner and Shakespeare,” she observed in a letter to longtime friend and historian Nell Irvin Painter, “but none of us were told how to look at Toni Morrison or Sarah Wright.”

To address this gap, in the early 1980s McKay initiated what she called her “project.” This was, quite simply, a “turn toward black women’s writings” as an area of critical inquiry. Both simple in its focus and radical in its proclamation of the sovereign value of Black women’s literature, McKay’s project was rooted in lessons from an earlier time—specifically, lessons gleaned from her proximity to Boston’s Black feminist ferment of the 1970s. A glimpse into the community of Black women in the Boston area that shaped McKay’s vision of a field of Black literary studies inclusive of Black women’s voices reveals the power of Black feminist collaboration in field formation and the steps McKay took to extend herself to a community that would build her confidence, inspire her to persist in her studies, and set her on a path to bring Black women’s literature from the shadows into the light.

*

The Boston-based Combahee River Collective, led by Barbara Smith, Demita Frazier, and Beverly Smith, produced what would become a seminal text in Black feminist theory: The Combahee River Collective Statement: Black Feminist Organizing in the Seventies and Eighties (originally published in 1977). It is a slim volume, approximately twenty pages total. But what it lacks in length, it more than makes up for as a radical statement of Black lesbian feminism and for what its grassroots method of dissemination teaches about early Black feminist organizing. The Statement was named for a river in the South Carolina Low Country, the Combahee River, since it was on this site in 1863 that Harriet Tubman masterminded and, with help from 150 Black Union troops, executed the Combahee Ferry Raid. The raid itself “freed 750 enslaved people”; but it was Tubman’s leadership as “the first woman to lead a major military operation in the United States” that inspired the authors to name the Statement in her honor.

McKay was part of a coterie of Black women graduate students in the Boston area who formed a “women’s study group” committed to the recovery and dissemination of Black women’s literature.The Statement was one of several foundational texts penned by Black women in the 1970s that helped form the field of Black feminist thought, shaping the vocabulary Black cultural critics use even now to reckon with current events. Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor elaborated: “It is difficult to quantify the enormity of the political contribution made by the women of the Combahee River Collective. . . because so much of their analysis is taken for granted in feminist politics today.” While “intersectionality” is typically attributed to Kimberlé Crenshaw’s 1989 article “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex,” Taylor continued, the CRC introduced this concept when they identified “interlocking” forms of oppression that created “new measures of oppression and inequality.” The collaborative nature of their work was reflective of strategies that introduced McKay to a burgeoning framework of 20th-century Black feminist thought and methodologies of Black feminist organizing. These collaborations, through reading and study groups, were foundational to how the women learned together; these groups were also instrumental to how McKay began to imagine the possibilities of Black women’s literature as a field that warranted the attention of Black feminist thinkers and institutional tastemakers.

In the early 1970s, McKay was part of a coterie of Black women graduate students in the Boston area who formed a “women’s study group” committed to the recovery and dissemination of Black women’s literature. Sometime after joining the Simmons faculty, a post she accepted while on temporary leave from her graduate studies at Harvard, McKay was invited to a dinner at the home of Andrea B. Rushing, who was “then an instructor in the Afro-American Studies Department at Harvard.” In McKay’s memory of the gathering, it was a “nice warm spring night” when a group of Black women graduate students gathered at Rushing’s to discuss Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God. McKay took the train to Roxbury, climbed the hill to Rushing’s, and joined a who’s who of Black feminist graduate students and early-career faculty to discuss the book.

As mentioned in Mary Helen Washington’s foreword to Their Eyes, Rushing remembered McKay, Combahee cofounder Barbara Smith, and Wesleyan University professor emerita Gayle Pemberton in attendance. McKay recalled Hortense J. Spillers and Thadious M. Davis, too. Mostly, these women were either teaching at local colleges (Amherst hired Rushing to teach English and Black studies in 1974) or on their way to earning degrees at institutions that included Harvard (McKay and Pemberton), Brandeis University (Spillers), and Boston University (Davis). Smith, who had earned her BA from Mount Holyoke College in South Hadley, Massachusetts, returned to the Boston area after earning her MA in literature from the University of Pittsburgh. Boston brought them together, but Black women’s literature bonded many of them for life.

Once everyone had assembled, Rushing posed a question to the group. McKay recalled: “And Andrea said, ‘Well, I brought you here because I want us to talk about something that is really serious.’ And she said, ‘Have you thought about the question, Where are the women?’” After that, according to McKay, it was pure bedlam. The room exploded. Until that time, the women in attendance had primarily been reading the men. James Baldwin, Ralph Ellison, and Langston Hughes were ever present, but the women, by and large, were absent. McKay only “had any real sense” of one woman: Gwendolyn Brooks, the first African American to win the Pulitzer Prize, for Annie Allen in 1950. The women present were “all in fact teaching by then,” so they took advantage of that fact and began teaching texts by Black women: “So we started copying everything and sharing” because, at the time, many of the books they wanted to teach were out of print. Even though McKay was unclear about the first text they circulated, she remembered Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God being one of the first.

They shared titles and taught the texts. Then they used “these little three-by-five cards,” the ones once clustered together in card catalogs, now relics of the research library, to search for other sources and reclaim more of the literature. In the end, “it wasn’t like we reinvented it. We didn’t invent it. It was just there, sleeping.” This experience informed McKay’s teaching at Simmons by putting her on the cutting edge of a field that was being formed by Black women who created intellectual communities geared toward elevating the literature of their sister writers. This, along with Alice Walker’s teaching of the first class dedicated to Black women writers at Wellesley College during the 1971–1972 school year, moved Black women’s literature a step closer to becoming a field unto itself. At the same time McKay began to imagine moving the literature of Black women from the critical shadows, she committed to keeping details of her personal life hidden from public view.

She couched her achievements within a broader narrative of Black women’s intellectualism instead of sharing her successes as a story of inspiration.As a graduate student at Harvard and as a professor at Simmons, McKay decided that she would not tell her professors, classmates, and peers that she was a divorced wife and mother of two, or that Patricia “Pat” Watson—enrolled at Radcliffe—was her daughter, so that she would be defined by the quality of her work, not the theater of her personal life. McKay wanted to fit in among her peers even if, as a Black woman, she could not belong. In the privacy of her graduate school application, she mitigated one personal detail that she thought might raise eyebrows: her age. In the section that required her name, date of birth, and marital status, McKay shaved two years off her age and identified herself as a divorced mother of two. The latter was true. The former was not. Two years isn’t much, but perhaps McKay imagined that if she positioned herself closer to 35 than to 40, the selection committee would be more likely to support the institution’s investment of time and resources in the burgeoning scholar and admit her.

In all other parts of the application, however, McKay was faithful to the facts. A Harvard degree would help McKay achieve an “independent black female selfhood,” a topic she would later explore in essays about Harriet Jacobs, Mary Church Terrell, and Anne Moody. Furthermore, her study with other Black women in the Boston area taught her the value of group ascent, so she couched her achievements within a broader narrative of Black women’s intellectualism instead of sharing her successes as a story of inspiration. She would not be known as “an older woman who had raised a family and was going back to school.” She wanted to be commended for the fruits of her labor, not congratulated for overcoming personal obstacles. McKay took a leave from Harvard when the climate and curriculum felt overwhelming; teaching at Simmons while she was on leave built her confidence and confirmed her commitment to impacting students through the study of literature.

By the time McKay resumed her studies at Harvard, she was a different person. At Simmons, she had been nurtured into confidence by colleagues who valued her contributions and by students who trusted her guidance. She reenrolled, more secure in her abilities and confident in her capacity to see the PhD through to completion. “I stayed away for two years and then I reenrolled,” McKay recalled, “but I had a very different sense of myself when I went back. I had done something on my own and I had a different life and I was no longer intimidated.” Alongside Simmons colleagues Lawrence L. Langer, Pamela Bromberg, and David Gullette, McKay had fashioned a life that existed beyond the reach of her Harvard professors. She saw herself with new eyes. Department chair F. Wylie Sypher encouraged McKay by reminding her that Simmons “shouldn’t be the end of the street.” Earning her doctorate, then, was nonnegotiable both in McKay’s mind and in the minds of those around her. Her ambition reignited, she knew that it was all part of a bigger plan: “There was a life that I said I was going to have; that required that I finish my graduate degree.” She returned to Harvard ready to complete her doctorate and pursue the life she wanted. Possibilities awaited on the other side.

__________________________________

Adapted from Half in Shadow: The Life and Legacy of Nellie Y. McKay by Copyright © 2021 by Shanna Greene Benjamin. Used by permission of the University of North Carolina Press.

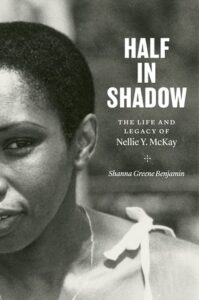

Top photo credit: Nellie Y. McKay celebrates The Norton Anthology of African American Literature at a party hosted by Susan and Ed Friedman, Madison, Wisconsin, circa 1997. Photograph courtesy of Susan Stanford Friedman.