How My Friend Hilary Mantel Got Inside People's Minds

Miranda Miller on What Mantel Believed Was a Novelist's True Business

I first met Hilary Mantel when my volume of short stories about Saudi Arabia, A Thousand and one Coffee Mornings, was published. She reviewed it generously in the Daily Telegraph and then phoned to suggest a meeting.

We met in an Italian coffee shop in London’s Gloucester Road and bonded over our mutual resentment of misogyny in Saudi Arabia, where we’d both lived. I’d put off reading Eight Months on Ghazzah Street, Hilary’s novel about expatriate life in Saudi Arabia, until I’d finished writing my stories but when I did read her novel I admired it hugely.

She talked about the novel she was planning to write next, about an eighteenth-century Irish giant who was viciously exploited and pursued by the surgeon John Hunter because he wanted to get his hands on the giant’s remarkable skeleton. That, of course, became The Giant, O’Brien, her eighth novel. I thought it sounded wonderful.

Of all the writers I’ve known, Hilary was the most single-minded.

She spoke of her identification with her Irish Catholic heritage although she grew up in England, in the village of Hadfield in Derbyshire. We discussed books and politics and at that first meeting I was impressed by her wit, deep intelligence and kindness, a rare combination. That coffee took three hours and was the beginning of a friendship that lasted until her death. We wrote letters, had long entertaining telephone conversations and later wrote each other emails.

At first, I thought of her as a brilliant comic novelist in the brittle tradition of Muriel Spark, who we both admired. I loved Hilary’s first novel, Every Day Is Mother’s Day, a hilariously grotesque story about Muriel Axon, who lives with her dreadful mother Evelyn in a house full of hoarded rubbish and family secrets. They loathe each other but can’t escape. This nightmare portrait of suburbia is a recurring theme in her fiction.

Hilary had an unhappy childhood and detested the nuns at her convent school. Fludd, her fourth novel, could only have been written by a cradle Catholic. Fludd, who comes to a remote village in the north of England as a curate, may or may not be a reincarnation of the sixteenth-century mystic and alchemist Robert Fludd. A young nun, Sister Philomena, falls in love with him and flees from the convent. Again, this novel has a powerful and wildly eccentric atmosphere; it’s funny, gruesome, mysterious and totally original.

Hilary once said that as a schoolgirl at her strict convent she became interested in the French Revolution because she thought it was a very good idea to abolish nuns. The first novel she wrote, but the fifth to be published, was A Place of Greater Safety, an immensely ambitious and original take on the events of the revolution. The main characters are Georges Danton, Camille Desmoulins, and Maximilien Robespierre. The dialogue sparkles and the novel is richly imagined. Reading it, I realized that she was a universal writer, impossible to pigeonhole, fearlessly attempting new territory with each book.

Of all the writers I’ve known, Hilary was the most single-minded. In her twenties she was diagnosed with endometriosis and was in constant pain and discomfort. A doctor overprescribed steroids and as a result she gained five stone in weight which she was never able to shed. For a vulnerable and sensitive woman this feeling that she was trapped in the wrong body was a kind of torture that gave her immense empathy for the suffering of people with eating disorders. She never forgot how it felt to be powerless and gave generous emotional support to many other people as well.

“For most of my career I wrote about odd and marginal people,” Hilary said in 2017. “They were psychic. Or religious. Or institutionalized. Or social workers. Or French.”

Bill Hamilton, her lifelong agent and friend, said of her at the memorial service at Southwark Cathedral last April: “There was always a slight aura of otherworldliness about her, as if she saw and felt things us ordinary mortals missed.” I felt this very strongly and it was the strangeness in her novels that I valued most.

For me Beyond Black, her ninth novel, is the one that brings together her unique gift for comedy, her sympathy for outsiders and her perception of the unheimlich. Alison is a medium, a woman of “unfeasible size,” both a charlatan and someone with a genuine gift. There are magnificent descriptions of the desolate suburbs, the landscape of Hilary’s first two novels, where Alison performs her sleazy gigs:

“Traveling: the dank oily days after Christmas. The motorway, its wastes looping London: the margin’s scrub grass flaring orange in the lights, and the leaves of the poisoned shrubs striped yellow-green like a cantaloupe melon. Four o’clock: light sinking over the orbital road. Teatime in Enfield, night falling on Potters Bar.”

Hilary’s ghosts and spirits are never romantic. Morris is Alison’s repulsive, violent, masturbating spirit guide. Alison hates him but can’t get rid of him:

“Other mediums have spirit guides with a bit more about them—dignified impassive medicine men or ancient Persian sages—why does she have to have a grizzled grinning apparition in a book-maker’s check jacket, and suede shoes with bald toecaps.”

In an interview in 2017 Hilary said, “My readers were a small and select band until I decided to march on to the middle ground of English history and plant a flag.”

Just before Wolf Hall was published Hilary told me that she and Gerald were worried about being able to repay the mortgage on their house. The immense and deserved international success of her Thomas Cromwell trilogy gave her the freedom to move from Surrey to Budleigh Salterton in Devon, where she had spent an idyllic holiday as a teenager.

“As soon as I get the idea I understand someone I feel it is a good corrective to remind myself I probably don’t.”

Looking through her emails, she wrote in 2013:

It makes me so happy that you are happy. I am too, with my work, with Gerald, with my new home, with everything but my health. But it was explained to me that the recovery from the surgery I had in 2010 would not be simple, so I am trying to be patient.

Two years later she wrote about the problems she was having writing The Mirror and the Light, the third volume of her trilogy:

The difficulties: the early part of his life is missing. The later part is preserved in exhaustive detail. Yet we still seem to know nothing about him. He is the most unrevealing of letter writers. The turning point for the imagination comes when you start to think, Is he doing this deliberately? What is he hiding? Is he hiding from the reader, or from his contemporaries, or from himself? Then when you ask that last question, you are in business (a novelist’s business).

You are beginning to feel your way inside the person. But you must beware of the corrupting power of empathy and keep going back to the evidence.

When I questioned what she said about empathy she replied:

By the corrupting power of empathy, I don’t mean you shouldn’t follow your instincts. I mean you should be wary of projecting modern attitudes or your own sensitivities backwards in time. As soon as I get the idea I understand someone I feel it is a good corrective to remind myself I probably don’t.

In 2017 she wrote:

For so many years it’s been a case of work and sleep/recovery, little room or energy for anything else, and my life has been narrow and constrained. But I am beginning to glimpse other possibilities. You’re right, the sight of the seas each morning is wonderfully restoring.

Like me, Hilary felt that Brexit had been a disaster and was depressed by the rightward, xenophobic drift of English politics. She and Gerald decided to move to Ireland and on the 10th of September, 2022, she wrote:

We complete on our deal in Ireland on Tuesday, if no further delays arise. Their system is very like the British system—that is, designed to induce despair. We are not near to completing in Devon, and our buyer (a neighbor, who seemed completely sound) now proves to be in financial difficulties—she made an offer before we even went to market, and so we have no backup plan.

So it’s grim here. Whatever happens about the sale, we leave here on 24th. Superstition prevents me giving out my new address till we are in Kinsale, but my email will be the same. Next week sees the publication of The Wolf Hall Picture Book, so we have a trip to London before our final week’s packing.

I sympathize with all you say. Ireland seems to be one of the few countries moving in a more liberal and tolerant direction. Unfortunately the weather is wretched—I sympathize there too. I would have preferred to go in the direction of gentle sunshine, if any was to be found under a decent regime.

I will be in touch. Keep smiling.

I imagined her living contentedly in Ireland, a country she’d always loved, and was devastated when I heard, only 13 days later, that she had died of a stroke.

What would she have written next? At her memorial service at Southwark Cathedral a few paragraphs of her unfinished novel, Provocation, were read aloud. This was going to be the story of Pride and Prejudice from the acerbic point of view of the plain, unaccomplished sister, Mary Bennet, whose father memorably tries to stop her singing in her flat voice by saying, “You have delighted us long enough.” It would have been witty and brilliant and nobody else could have written it.

I miss Hilary and will always miss her. I realize that I was very lucky to have known her and often dream about her.

__________________________________

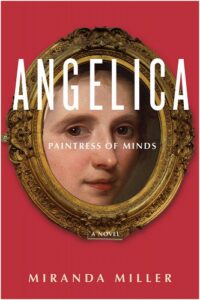

Miranda Miller’s eighth novel, Angelica Paintress of Minds, about the eighteen-century artist Angelica Kauffman, has just been published in the US by Barbican Press.

Miranda Miller

Miranda Miller is a Londoner who has published eight novels, a book of short stories about Saudi Arabia and a book of interviews with homeless women and politicians. She was a Royal Literary Fund Fellow at the Courtauld Institute and works as a reader and mentor for The Literary Consultancy. You can find out more about Miranda at mirandamiller.info.