How Music and Verse Can Spark Literary Passion in Reluctant Readers

Alicia D. Williams on the Many Written and Oral Forms a Story Can Take

As a kid, reading was not an interest of mine. I found no joy in the teacher assigned phonics. Having Fun with Dick and Jane lacked adventure, emotion, and representation. Then music entered my world, and that was the hook that made me fall in love with stories.

At eleven years old, I recall sitting by our record player spinning Deniece Williams’ “Silly of Me” over and over until I memorized every single word. I copied her longing lyrics into my notebook, ready to angrily shove the paper at a future boyfriend who was sure to crush my heart. Her verses captured my youthful angst of desire for love and fear of rejection. Music took me places.

Friday nights, I zoomed to space on a Parliament-Funkadelic spaceship, learning new vocabulary from wild song titles from the back of my father’s albums. Saturday afternoons, I got lost in similes on lonely streets of Portugal as Tina Marie belted Portuguese Love. And Sunday mornings, The Clark Sisters’ You Brought the Sunshine rocked my core with rhyme and non-rhyme phrases.

Many young people are reluctant readers, and I wonder if for some, music holds the key.

Songs opened my eyes to the power of words. And words freed me. I scaled mountains, escaped leopards, and dodged avalanches in the choose-your-own-adventure books. My rib cage was tickled by Judy Blume’s Fudge and Super Fudge. Blubber taught me I wasn’t alone in being bullied and bodied shamed. I was privy to discussions my parents weren’t too keen on having in Are You There God, It’s Me, Margaret? Maya Angelou shared her blanket of security in I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings and whispered how we both held a shameful secret. These stories offered me entertainment, escapism, hope, and healing. It was as if the authors saw me. I wished everyone knew the mysteries and wonders held inside of books.

Truth is, many young people are reluctant readers, and I wonder if for some, music holds the key. Books with pages of paragraph after paragraph are a turn off. So, how can we lure young readers to read? As I ask this question, I think back to the music—the verse—that I connected with as a child. Poetry is much like music. So, could this be the form to hook these readers?

For young me, poetry was the bland lines given to memorize for Easter—Why you all looking at me? I just come to say, Happy Easter Day. As a teen, it was stern phrases, abstract landscapes, foreign similes, and metaphors that required codes to crack. In college, I sat lost but pretended to be excited as my peers discussed their favorite sonnets.

Then finally, I discovered Nikki Giovanni and Maya Angelou (she wrote poetry, too?!). Their words were the food that developed my poetry palate. I devoured “Nikki-Rosa” and “Ego Tripping.” I licked the plate clean of “Phenomenal Woman,” and “Still I Rise.” I wanted more, needed more. I bought Eloise Greenfield’s Honey, I Love for my daughter and spoon fed her poems at bedtime.

Poetry can be intimidating to struggling readers, yet novels-in-verse appeal to this demographic. The first verse novel I read was Karen Hesse’s Out of the Dust. I was amazed at the concise word usage, yet it was full of imagery, sensory detail, and characterization. I read Jasmine Warga’s Other Words From Home. And empathized with Syrian immigrant, Jude, and her angst to fit in and having to be the new “different” girl. The language of these novels was beautiful, lyrical, and accessible. Like music.

I once had a two-week artist residency at middle school. Administrators wanted students to write poems in hopes it would raise morale. I was versed in creating monologues, short stories, and folktales, but not poetry. Children were failing standardized tests; many were transplants; others were residents at the nearby homeless shelter; and teachers were exhausted and frustrated. If I was to reach these fifth graders, then I had to dig deep. Drawing from my own childhood experiences, I decided to look to song lyrics .

Through hip-hop and pop, I introduced similes—lyte as a rock—metaphors—thinkin’ how I can get some dead presidents—imagery—like a grasshopper hoppin’ on the morning lawn—plus rhythm and cadence too.

During presentation time, fifth graders sat in the gymnasium sharing poems. A girl strode to the microphone, paper shaky in her hands. She took a breath and began to spit her poem. She rapped about her brother, how he was shot down in front of her and their mom, and how she missed him. Tears rolled down her cheeks, but she kept on. Teachers eyed each other in shock, and still she kept rapping her poem.

Teacher Justin O’Dell explains why this form is a good format: “Novels written in verse are usually smoother and help build stronger, emotional connections helping readers become more emotionally engaged in the material. This engagement often leads to a higher rate of completion for young or struggling readers. This of course leads to a more confident reader who is in turn ready to pick up his or her next read.”

It is most gratifying to know that through the power of verse novels, young readers can confidently explore stories in all forms.

Verse novels present stories in a reader friendly text. Compared to prose novels, novels-in-verse leaves more white space on the page which makes reluctant readers feel less intimidated. Each poem is a chapter, even if it is one stanza, and these bite sized portions make the reading experience more manageable. Upon completion of these “chapters,” students feel a sense of pride. And encouragingly, this form of storytelling prepares readers for longer narratives.

In order for a student to become a lifelong reader, teachers advise that they need the right book. I also believe they need the right book in the right form. This is evidenced by the popularity and success of Elizabeth Acevedo’s The Poet X and Jason Reynold’s Long Way Down. These lyrical verse novels are full of energy, musicality, and amazing storytelling. Plus, the protagonists deal with real life issues and consequences that draws in apathetic, discouraged, and curious teens. Children need to feel seen, they want answers, and to know that they are not alone. They want to laugh, wield magic wands, and take adventures too. Books are essential to not only providing emotional support, hope, and guidance, but also provide the building blocks to comprehension, vocabulary, imagination, innovative and big picture thinking.

Many days I spent by the record player visualizing my future love, floating on Mars, and strolling through Portugal’s streets which led me to nestle in the comfort of Judy Blume and Maya Angelou. If I didn’t have these outlets, I’m not certain I would have had the necessary tools to examine my feelings or cement my identity.

Even so, I wish I could admit that my love of books bloomed to happily-ever-reading, but sadly I went through my early adult like as if books were only a passing phase. The seeds were sown but didn’t take root. Inside of me was still the reluctant reader who was now intimidated by lengthy narratives. If I had had verse novels to bridge the gap, I would have read more novels and sailed across oceans, defeated evil foes, toasted glasses with lovers, and made many more discoveries. Yet and yet, it is most gratifying to know that through the power of verse novels, young readers can confidently explore stories in all forms.

__________________________________

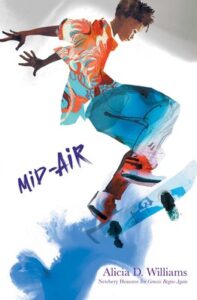

Mid-Air by Alicia D. Williams, illustrated by Danica Novgorodoff, is available from Atheneum/Caitlyn Dlouhy Books, an imprint of Simon & Schuster.

Alicia D. Williams

Alicia D. Williams is the author of Genesis Begins Again, which received Newbery and Kirkus Prize honors, was a William C. Morris Award finalist, and for which she won the Coretta Scott King - John Steptoe Award for New Talent; and picture books Jump at the Sun and The Talk which was also a Coretta Scott King Honor book. An oral storyteller in the African American tradition, she lives in Charlotte, North Carolina.