How Michele Wallace Sought Black Women’s Liberation Through Art

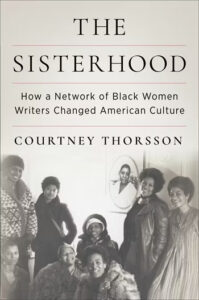

Courtney Thorsson on the Emergence of a Black Feminist Literary Culture in America

An extended community nurtured the achievements of The Sisterhood. Many other Black feminist groups and individual intellectuals in the 1970s and early 1980s shared The Sisterhood’s goals of publication and publicity for Black women writers, as well as the belief that political and social change could and should be made through culture. In this larger network of Black women literary activists, the group mattered to and benefited from the work of women who were not official members of The Sisterhood. Michele Wallace, Toni Cade Bambara, and Cheryll Y. Greene are especially important for understanding The Sisterhood’s impact. Wallace engaged, sharpened, and extended the group’s Black feminist ideas into literary and cultural criticism. Bambara extended their advocacy for Black women’s writing into the South and was an important friend and interlocutor, especially for Toni Morrison. Cheryll Y. Greene collaborated with Sisterhood members to get Black feminist thought into Black mainstream culture on the pages of Essence magazine.

*

Michele Wallace is best known as the author of Black Macho and the Myth of the Superwoman, but that is just one work in her long career as a scholar, writer, activist, and cultural critic. Wallace is a scholar of African American cultural production and a keen observer of Black collectives. Her thinking about various organizations is visible in her archive at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, which includes copies of minutes from The Sisterhood’s meetings; a newsletter, writers’ workshop program, reading list, and regional conference program from the National Black Feminist Organization (NBFO); and a draft platform for the Black Feminist Organization of the National Organization of Women (NOW), all with Wallace’s handwritten notes and edits. She kept track of, supported, and criticized these organizations. Her published writings and personal correspondence attend to the stakes, limitations, and legacies of Black feminist groups of the 1970s. Like that of many Sisterhood members, Wallace’s Black feminist work moved from political organizations into literary and cultural organizing in the 1970s and then into the academy in the 1980s.

Wallace was committed to feminism and committed to making interracial feminist groups work for the liberation of Black women.By the time The Sisterhood began meeting, Wallace had connections with many of its members and to its mission. She had already tested the waters of several other collectives in her search for community. When applying to college, Wallace fantasized that Howard University would be “a super-black utopia where for the first time in life I would be completely surrounded by people who totally understood me.” Once there, she “sought out a new clique each day and found a home in none,” but did find some community hanging out with the women who “stayed in on Friday and Saturday nights on a campus that was well known for its parties and nightlife.” Wallace’s disappointment in the colorism and sexism she encountered in college and her appreciation for being in a group made up exclusively of Black women shaped her ongoing search for and sharp critiques of other groups.

Wallace began a “black women’s consciousness-raising group” in New York City in the early 1970s, and then she and her mother, artist Faith Ringgold, helped found the National Black Feminist Organization (NBFO). At the same time, Wallace continued her studies at City College, where she met future Sisterhood members Audre Lorde, Toni Morrison, Alice Walker, and June Jordan. She began reading Walker’s work around the time that Walker led an NBFO workshop with Ringgold on Black women in the arts. After earning her bachelor’s degree in English in 1974, Wallace continued to seek, but not find, solidarity and support in Black spaces including the National Black Theatre (NBT). She discovered that the NBT’s “brand of a consciousness-raising session” meant hearing about “the awful ways in which black women, me included, had tried to destroy the black man’s masculinity.” The “Black Power antics” and “misogyny run amok” Wallace had encountered at Howard also plagued the NBT. By the mid-1970s, she was working as a secretary at Random House while Morrison was there and later wrote that “even then, to fledgling black women writers, Morrison was a queen.” Wallace became a researcher at Newsweek with Margo Jefferson and then started teaching journalism at New York University, a position she got partly on Jefferson’s recommendation. The job at Newsweek granted Wallace “entry to all sorts of magic New York worlds from the Newport Jazz Festival to the Public Theatre [sic] to a variety of literary shenanigans and shindigs,” but it also meant being in an overwhelmingly white office.

Facing racism in white workplaces and sexism in Black educational and cultural institutions, Wallace turned to collaborations with Black women, such as with Ringgold, Jefferson, and Patricia Spears Jones to organize the 1976 Sojourner Truth Festival of the Arts, where Ntozake Shange was among the performers. The Sojourner Truth Festival was a rare, even singular, event in that it focused on Black women filmmakers. It was also “the scene of a major public confrontation between” Wallace and her mother, Faith Ringgold, “that resulted in a lot of tears” and Wallace moving out of her mother’s house. By that time, Wallace had already been advocating for Black women visual artists since 1970, when, at only eighteen years old, she founded Women Students and Artists for Black Art Liberation (WSABAL) “as an activist and polemical unit” that “participated in raucous art actions at the Museum of Modern Art and the Whitney” and “occupied offices” at other New York City museums to protest the lack of Black women artists in their exhibits. By the time The Sisterhood began to meet, Wallace was connected with many of the group’s members, working to change the landscape of visual art, and regularly writing for the Village Voice. Based on her experiences with other groups, she was also justifiably skeptical of the ability of collectives to create significant political change or provide a refuge for Black women. She was “hungry for the kind of fame” that Ntozake Shange had, partly because Wallace thought that celebrity might be the only kind of power available to Black women in the late 1970s and feared “that the possibility of radical politics was over.”

Wallace’s commitment to Black women’s literature and liberation made her an invested ally of The Sisterhood; her distance and skepticism also made her an acute observer of the group and the broader terrain of Black feminist collectives. Wallace was aware of The Sisterhood from the time of its first meeting and was at the time in a different Black feminist study group with Barbara Omolade and Sisterhood member Susan McHenry. In a 1995 essay, Wallace wrote that “a more informal discussion group of black women writers called The Sisterhood began meeting at Alice Walker’s house in Brooklyn. Attendees included me, Toni Morrison, June Jordan, as well as virtually every significant black female writer of the next decade.” Wallace is not listed among the attendees in any archived meeting minutes and Sisterhood members do not recall her being there, but she may have been at later meetings that are not documented in archived minutes. Her correspondence with Alice Walker suggests that, despite her absence from the minutes, Wallace may have attended one meeting and decided not to return.

Wallace’s commitment to and experience with the Black feminist activism of NBFO and other groups with national reach may have been part of the reason she declined to attend Sisterhood meetings, despite Walker’s repeated invitation. Wallace’s and Walker’s references to The Sisterhood appear their 1977–78 letters, which discuss Black Macho, literary scholarship about Black women’s writing, and essays that might be published in Ms. In a letter to Walker of March 25, 1977, Wallace writes,

As for The Sisterhood, I find I must devote most of my time to my book if it is ever to be finished. Also I am a little disturbed by the way the thing is progressing. I promised myself a while back that I would never seriously commit my time to any organization that wasn’t feminist and working toward the alleviation of the problems of black women. If it is to be a discussion group for black women artists who understand that they are black women, then I may attend. But if the goal is to organize a publishing company which will reissue out-of-print works of black men, and to found a magazine which will give space to black men, I can’t possibly imagine what I would be needed for. I can’t understand why a group of black women would do something like that. I have a great deal of respect for you Alice, but I just can’t come to the meetings as long as these things aren’t seriously discussed because I’ll get nasty and I try to avoid doing that. If things take a turn for the better I would be happy to hear about it.

Wallace’s reasons for not participating in The Sisterhood shed light on the ideologies of the group. Wallace rightly notes that, unlike the NBFO or other explicitly politically organizations, members of The Sisterhood did not always or consistently use the term “feminist” to describe their collaborative work. Most members who are still living describe themselves as feminists today, but in the 1970s, they sometimes avoided the term because it evoked the white women’s liberation movement. Wallace was committed to feminism and committed to making interracial feminist groups work for the liberation of Black women. She chose her membership in various collectives accordingly.

In addition to the distinction in terminology, Wallace’s concerns in this letter reinforce that the work of The Sisterhood was literary and textual. In fact, the group did make plans to “reissue out-of-print works,” “found a magazine,” and “organize a publishing company.” Wallace did not see these goals as wholly feminist and political, perhaps because they include economic advancement within existing capitalist structures or perhaps she viewed them as too narrowly literary. For The Sisterhood the work of recovery and publication was political. It was also part of their broader focus on textual labor as necessary for Black women’s liberation. In Toni Cade Bambara’s words, they all agreed or eventually came around to the idea that writing is “a perfectly legitimate way to participate in struggle.” Sisterhood members were keenly aware that they were “black women” and were explicitly concerned with advancing the work of Black women writers, which they understood as an important political project.

Walker responded: “There is no stigma attached to not attending, just as there is no coercion for attending. We come if we wish. If not, that’s cool. As for what we discuss: we are black women, and the least that should mean is that among ourselves we discuss what we like.” Walker’s description of The Sisterhood as more casual than the minutes or other member’s descriptions suggest was likely a poor recruiting tool when it came to Wallace. Her commitment to Black women’s art and literature is clear in her correspondence with Gloria Steinem and others at Ms. on behalf of WSABAL. In a letter to Steinem of May 27, 1975, Wallace offers data demonstrating that “the magazine has generally not covered black women or employed black women writers to any extent that might be considered adequate or even acceptable.” She notes that Margo Jefferson and Alice Walker are responsible for the “one article on a black woman singer” and “one on a black woman dancer,” respectively, and goes on to point out that the few articles in Ms. about Black women perpetuated stereotypes in articles by “white feminists dwelling on our poverty and deprivation.” The relative absence of Black women from the pages of Ms. amounted to a “racist policy” that Wallace urged Steinem to rectify, in part, with “a series of feature articles on black women artists.” Although The Sisterhood focused their efforts mostly on Black periodicals such as Essence and Black World, Wallace was arguing for exactly the increased, varied, and Black-authored representation of Black women in magazines that The Sisterhood would also soon advocate. Wallace’s proposal for a Ms. series on Black women visual artists is similar to Vèvè Clark’s proposal on behalf of The Sisterhood for Ebony to “establish a monthly, bi-monthly or weekly feature on the poetry of one black woman.”

Wallace had learned that being the rare Black women writer to receive significant media attention was an unbearable weight.Wallace’s correspondence with Steinem shows her investment in intervening in white feminism. Wallace, Susan McHenry, Barbara Omolade, and Audre Lorde participated in predominantly white feminist events such as the Barnard Scholar and Feminist Conference and NYU Second Sex Commemorative Conference, both held in 1979. They also “pursued writing and public speaking in feminist circles” and publication in feminist media. Wallace writes that Steinem ought to be “interested in altering your racist image among black feminists” and makes clear that the stakes are nothing less than that “The Women’s Movement is being transformed into a cultural dictatorship by racism.” Even the most cutting parts of Wallace’s letter demonstrate her sincere investment in the movement and belief that it could and should participate in the project of Black liberation. Correspondence between Wallace and Ms. in the spring of 1975 indicates that editors of the magazine agreed and shows that Wallace, at the magazine’s request, offered a detailed plan for a series of articles on specific Black women visual artists and specific exhibitions of their work. Her work and The Sisterhood’s subsequent efforts succeeded in making Black women’s visual art, political activism, and literature more central to the content of Ms.

From the start of her career to the present, Wallace’s essays have drawn attention to works by Sisterhood members and other Black feminists. Her writings about literature in newspapers, magazines, and academic journals became part of Black feminist literary criticism that secured and educated a readership for Black women’s books. In 1995, Wallace wrote an essay reviewing a new book by Stanley Crouch, a vocal critic of Shange, Wallace, Walker, and other Black women writers. Rather than respond in kind, in a move typical of her investment in Black women’s writing, Wallace uses the occasion of reviewing a book by Crouch to historicize Black women’s literature and celebrate Morrison’s Beloved:

Beloved is Toni Morrison’s brilliant [fifth] novel, not only the linchpin of her oeuvre, but the ultimate accomplishment of black women’s fiction and black feminist thought of these past twenty years since the publication in 1970 of the novels The Bluest Eye and Alice Walker’s The Third Life of Grange Copeland, Maya Angelou’s autobiography I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, and Toni Cade Bambara’s collection of essays, The Black Woman…Beloved may be as close as we’ll ever get to the dream of a black feminist theory grounded in the historical experience of the black.

This review of Crouch’s Notes of a Hanging Judge: Essays and Reviews, 1979–1989 also declares Morrison’s writings as both exceptional and representative of an African American literary tradition.

Sisterhood members recognized that the focus on just a few Black women writers in the late 1970s and the 1980s meant that important literature by other Black women was not receiving the popular and scholarly attention it merited. Wallace was attuned to how market forces in the 1980s led publishers to focus on a select group of writers. From her own experience with Black Macho, she understood the dangers of increased visibility for Black women. Though she coveted Ntozake Shange’s “fame” in 1976, she regretted her own celebrity by the close of the 1970s: “I had indiscreetly blurted out that sexism and misogyny were near epidemic in the black community and that black feminism had the cure. I went from obscurity to celebrity to notoriety overnight,” and “the whirlwind began over the way I looked and dressed for TV appearances, the way I spoke, what I did and didn’t say…I don’t think anybody ever realized how paralyzed with fear I usually was in any kind of public appearance…Ms. wondered whether I was up to snuff as a black feminist spokesperson (I was not).” Wallace had learned that being the rare Black women writer to receive significant media attention was an unbearable weight. This was not just a painful personal experience; she understood that assigning “iconic status” to one Black woman writer forces that person to “stand in for the whole.” The purpose of treating one writer as singular, as the “black feminist spokesperson,” is insidious: “its primary function is to distract us from the actual debate and dilemma with which black feminist intellectuals, artists, and activists really engaged.”

__________________________________

Excerpted from The Sisterhood: How a Network of Black Women Writers Changed American Culture by Courtney Thorsson. Copyright © 2023 Columbia University Press. Used by arrangement with the Publisher. All rights reserved.