How Messy Can a

Rom-Com Be?

Carlyn Greenwald on Queer Romance and the Bounds

of Cis-Hetero Agenda

Up until I did it for the first time in 2019, I had never seen myself writing a rom-com. I was, like most edgy young adults, of the impression that most rom-coms adhered so deeply to a formula that there was no room for any interesting interpersonal conflict or realism to flavor the narrative. Which, of course, I now know wasn’t true. Each rom-com is unique as is every other book in every genre, but I still found myself grappling with an essential question—At what point does a rom-com stop being a rom-com?

Somewhere around 2018, my YA contemporary writer friends started writing adult rom-coms. As always, I would dutifully read their books—and started to fall in love with rom-coms in general. Yes, there was a formula, but there was nothing wrong with the formula itself. The books I was reading were poignant, full of conflict, sexy, and fun.

Still, even as I read deeper into the genre with a new love, it didn’t take away the detached feeling I felt reading them, especially in regards to representation. It was hard enough to find more than one or two Jewish/bisexual/anxious protagonists, but add in those who doubted themselves as much as me, who spiraled and made impulsive decisions and regretted? There were none. Each Happily Ever After brought home the weight of how different I felt.

Even when traditional publishing started slowly embracing sapphic titles, the ones who broke out like Something to Talk About by Meryl Wilsner had out and proud protagonists. They were wonderful stories to read and such important representation, but I was a romance reader still living my own messy coming out story. What would my story be if it was a rom-com? Could there be a protagonist similar to me, who was struggling in every aspect of her life from coming out to job prospects to family woes, and still have that happy ending? Could I feature all that angst?

So, when I started drafting my debut, a queer adult romcom about a newly out anxious Jewish bisexual working in Hollywood, my first impulse was to put every flaw and mistake I, and others like me, had experienced in the dating world more than anything to prove a point—my protagonist can be an actual MESS and still get a happy ending. But, as the emotional catharsis flowed through me, I was faced with a so-called rom-com that was, frankly, sad. It didn’t feel like a rom-com.

I hadn’t wanted to bend the rules of romance. I wanted to write a romance that romance readers would enjoy first and foremost. Genre fiction has always had to fight with literary works for legitimacy. Romance, historically defined as an insubstantial genre for women, has had a particularly difficult time not only been legitimized in mainstream society (whatever that means), but acknowledged for the work it’s done to push forward diversity and progressive ideas around love, sex, gender roles, and happiness.

Romance and its history, its writers, its tropes, and audience were bigger than me. I’d had the impulse to write a hopeful story for my marginalized protagonist and I had to respect what romance is to do so. But as I tore through rom-com after rom-com practically measuring how much space was dedicated to subplots revolving around a protagonist’s identity crises, mental health, dysfunctional family or work lives, or other darker topics, I found myself lost among the possibilities. Would there be room in a 300-page novel that had to hit every romance beat if it also included a ton about work, identity and family strife? Would the overall positive, fun tone suffer if the protagonist was too neurotic? Where is the line between quirky and neurotic?

In a story where the biggest thing at stake is a protagonist’s love, the stakes can’t get higher than that.

In the case of rom-coms, readers see an unfulfilled protagonist at the beginning and hope for happiness for them, swoon when they meet the love interest, laugh and yearn their way through the main couple’s courtship, feel devastated if/when they break up in the last third, and feel relief, joy and hope when they get together in the end. Readers are propelled through the narrative by romantic or sexual tension as well as conflict. In the many rom-coms I read, the protagonists would range from “quirky” but well put together otherwise—perfect lives where the only thing they were missing was love—to disasters who couldn’t hold down a job, maintain friendships, or knew what they wanted out of life on top of not finding love. But they didn’t feel as downer as the book I’d written. Why?

The interesting thing I realized is even in the novels with the ultimate disaster protagonist, I never felt the true anxiety for them I would if, say, that same disaster character was in a mystery or fantasy novel. There’s a silent promise at work that this disaster protagonist won’t end up homeless, won’t end up completely alone, won’t end up institutionalized for their mental illness. If there is death in a rom-com, it’ll be off the page. Not to suggest that terrible things don’t happen in the world, but they won’t happen on the page to this protagonist.

In a story where the biggest thing at stake is a protagonist’s love, the stakes can’t get higher than that. The worst pain a rom-com reader expects is the break up before the end of the book that will always end up resolved. So, I had to re-examine how I was going to incorporate my own protagonist’s demons while honoring the tonal expectations of a rom-com.

As I worked through revising that first sad draft of Sizzle Reel in 2019, I could already tell that somewhere deep in my heart, I could never write an escapist novel as some of my peers did (Courtney Kae’s In The Event of Love being one of my favorite examples). A book where being queer isn’t an issue, where every predominant character is accepting of all sorts of LGBTQ+ identities. I love reading those books and think they’re so important for readers to have access to, but it couldn’t be me.

The plot line felt unresolved, too messy for a story that should leave a reader feeling confident Luna and her love interest will be okay.

I couldn’t fully erase the anxiety from my protagonist’s brain, but as I kept developing the book, I realized that I could show that anxiety as long as I provided a safety net. Luna is in therapy when the book begins and as she goes through spirals, she has a supportive community of friends and family around her. Her love interest doesn’t reject her because of her anxiety. It’s a part of her, and it’s an antagonistic force, but it’s one that ultimately never becomes the problem.

The sexuality aspect was a bit tricker. I wanted the homophobia in the surrounding culture to pops up occasionally like a boogeyman to inform Luna’s growing anxiety (anxiety and sexuality is always intertwined). But when it came to internalized biphobia, I had a difficult time finding the limit.

One could argue that Luna’s attempt to live as a bisexual woman while still in deep denial about losing her straight privilege makes her so unlikable that it’s hard to root for her journey, especially as it affects others. She insists that she won’t have “lost” her virginity until she’s been penetrated by a woman, trying to establish an equivalent with the mainstream straight idea of “losing one’s virginity” being penis-in-vagina sex, a frustrating idea to write, but one I couldn’t get myself to delete. After all, I was writing this book to show an extreme of how confusing escaping cis-heteronormative culture is.

I went through so many iterations of that subplot, with softening layers added each time (think every other character telling her that virginity and sex can’t be defined). But still, the plot line felt unresolved, too messy for a story that should leave a reader feeling confident Luna and her love interest will be okay. And the last layer I added—a direct conversation Luna has where she processes the idea that sex can’t be strictly defined—when her anxiety finally stops, felt like enough for me.

It’s been a journey grappling with the “unlikable” lead in romance. The idea of an “unlikeable” character is thrown around so haphazardly among readers that it’s almost lost all meaning amid the inevitable misogynist, racist, ableist, and homophobic biases that create that impression. But I think part of what allowed me to feel satisfied in how I broke the mold was having read romances by other, more experienced authors. Every trait in existence was enough to label a protagonist as unlikable. Even as every protagonist fit into the expectations of romance—they all accept and love their love interest and don’t go out and murder anyone mid-book—they were still branded as unlikeable by someone. So, if the term has no meaning, I had to reject it.

As long as I loved my protagonist, that was enough. After so many years worrying that Luna was too messy to love, the best thing I could do was love her fiercely, flaws and all.

__________________________________

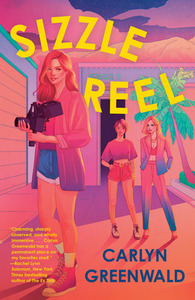

Caryln Greenwald is the author of Sizzle Reel, available now from Vintage, an imprint of Penguin Random House.

Carlyn Greenwald

CARLYN GREENWALD writes romantic and thrilling page-turners for teens and adults. A film school graduate and former Hollywood lackey, she now works in publishing. She resides in Los Angeles, mourning ArcLight Cinemas and soaking in the sun with her dogs. You can find her online at @CarlynGreenwald on Twitter and @carlyn_gee on Instagram.