How meme culture changed comedy writing.

Do memes live rent-free in your head?

The Workaholic writers’ room famously kept whiteboards of “over-done jokes” that were verboten. From edge to edge, you can find bits of brain decay dating back several years like rings on the brittle stump of pop culture: “Too soon?” “Laughy McLaugherson.” “We have fun.” “That’s not a thing.” “Little help?” “HARD PASS.”

This is important: the Workaholics writers room white boards with over done jokes pic.twitter.com/fbFgtn9ovW

— This Is Important Podcast (@podimportant) March 11, 2021

Scribbled into a word cloud, they read like a Too Many Chefs for comedy writing, both revealing and then scorching the very land on which the derivative writing used to stand. Once you read them, you can’t go back. Ten years ago, you would have called them cliches. Now, it feels semantically trickier.

Memes are by definition cliches—derived from Richard Dawkins’ observation that cultural behaviors replicate themselves in the Darwinian manner that successful genes propagate themselves. Mimesis is iteration until death, a process that takes around six months, per the research of Carlo M. Valensise et al (2022) into meme entropy.

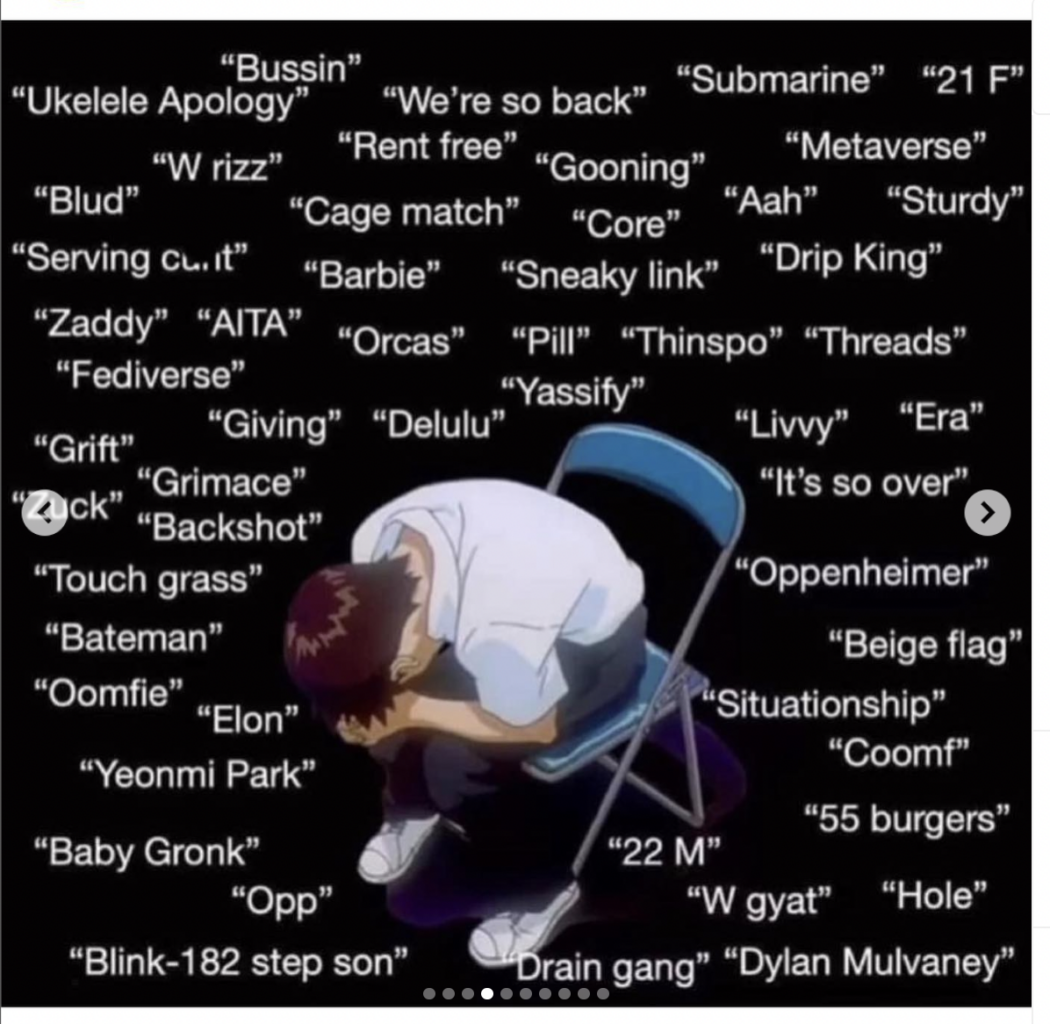

So it’s funny in a human centipede kind of way that retired-joke lists are now cropping up in online meme accounts. Take, for example, the below, which was reposted by @taylorlorenz3.0:

I don’t feel especially guilty of dropping “touch grass” or “it’s giving X” into my blog posts, but I’m sensitive enough to my audience that I know sometimes the obvious catchphrase would more easily add just the right dash of salt/pepper to spice up my lackluster writing than something esoteric. Meme culture has changed something about how we write and perceive a joke. There’s more anticipation, greater participation by the general public, and fewer ends to which a set-up can find its way.

“I think the rise of meme culture has given people the vocabulary to be funny in a really fun way at times. And it’s allowed people new ways to be publicly funny without creating standup/sketch/improv/essays,” says Josh Gondelman, a comedian and writer of TV, books, magazines, and his own delightful newsletter.

“However, I think it’s also given people a way to SEEM funny at times without doing the work of being funny. Like, using a familiar/popular gif to respond to something is not a joke or an insight. It’s like how 20 years ago someone would say: ‘You are the weakest link … goodbye.’

While the writers’ rooms he has worked in haven’t had an outright banned-joke list, they do tend to ask “are we leaning on a thing that’s someone else’s joke as our joke?” he explains.

It gets at that moment you probably recognize where, in Slack, for example, you drop the obvious joke that needs to be made at a given moment, without really laughing yourself. You’re participating in a more elaborate scheme of joke-pattern recognition, a performance of all being equally Online.

As Patricia Lockwood put it in No One Is Talking About This, “They kept raising their hands excitedly to high‐five, for they had discovered something even better than being soul mates: that they were exactly, and happily, and hopelessly, the same amount of online.”

That literacy with formulas means comedy writers have to work extra hard.

Comedian and writer Hari Kondabolu says he is always trying to think of new ways to “hide the joke” in his standup.

“People are more knowledgeable about comedy than they ever have been as a result of standup specials & clip culture on social media,” he says. “It takes a little more effort to misdirect them, but that’s part of the fun.”

But those novel formulations might not be immediately as “funny” as something more obvious. It might take time and a leap of faith to get to the point of appreciation.

The critical fever for Succession came in part from the coherence and strangeness of its world and language. To achieve that resonance, the writers were encouraged to fossick through their own lives for mundane details, and the actors likewise had their cliche radars turned high. Kieran Culkin told The New Yorker’s Rebecca Mead that Succession showrunner Jesse Armstrong is “allergic to shtick”:

“If it’s just a little bit—half an inch—too far-leaning into something, he’s going to catch it. On any other show, people would be, like, ‘Oh, that’s funny, let’s do that.’ And he’ll always be the voice of reason: ‘Yes, it’s funny, yes, it’s great, but it doesn’t work.’”

Here’s where my research falls short of my ultimate thesis, which is that the deployment of meme training wheels to the world at large has dulled our appreciation for truly inventive comedy: the chronically underappreciated comic novel (Gondelman gives a hat tip to Paul Beatty’s The Sellout and Patrick deWitt’s The Sisters Brothers), the purely comedic TV show that doesn’t sift in drama for weight, the joke that lands well outside the cornhole.

“The hard work of comedy in writing is, to me, obsessive attention to the line,” says my colleague Jessie Gaynor, whose very comic wellness-spoofing novel The Glow was published in June, “and a meme is by definition not that.”

She toiled away gathering material, vibes, tangents.

“My first draft(s) were literally just digressions … my editor was really going through being like insert plot here.”

The novel did not write itself, in other words.

Even writing this short blog post, I felt like I was walking a high-wire over a canyon of cliches, and maybe that’s part of what makes the writing so hard in the era of the meme—there’s a doublethink required at every step, a knowledge of the predictable joke (which may be less true, the situation dictated by the comic potential rather than the other way around) and the more difficult leap.

“We’ve been bombarded since our impressionable preteen years with fakery but at the same time are uniquely able to recognize, because of the unspoiled period that stretched from our birth to the moment our parents had the screeching dial-up installed, the ways which we casually commit fakery ourselves,” wrote Lauren Oyler in Fake Accounts.

We can inure ourselves to it, though that does sound like a lot of work. Womp.

Janet Manley

Janet Manley is a contributing editor at Literary Hub, and a very serious mind indeed. Get her newsletter here.