How Lew Alcindor Became Kareem Abdul-Jabbar

Scott Howard-Cooper on the Early Years of a Future Basketball Icon

The center of attention in a crowded room, prodding strangers, no hope of blending among fellow students for emotional refuge—he hated these moments even while mature enough at eighteen years old to handle them. Lew Alcindor was then, as he would always be, an ideal teammate in part because he preferred to deflect the spotlight, the antithesis to his dominating presence on the court.

The real joys were as in early 1963, as a high school sophomore at Power Memorial Academy in New York City when fellow Panthers staged a 7-Foot Party in the privacy of the locker room. He stood shoeless and backed against a pole, a teammate stepped on a chair and placed a ruler at the top of his head to draw a line, another unfurled a tape measure, and yes: seven feet tall. Lewie, as they called him, broke into a big smile and laughed along as the others jostled him in celebration before a player unveiled a doughnut-like pastry filled with jelly and topped by a candle to mark the occasion.

On May 4, 1965, though, senior Alcindor was alone among many. He stepped from the Power cafeteria into the gym at 12:33 p.m., wearing the school uniform of white dress shirt, dark blue slacks and jacket, and dark thin tie as several hundred sportswriters, photographers, TV crews, and radio broadcasters lined the room. Amid the snaking cables and equipment of the radio and TV men in the age of rapidly expanding electronics, appearing poised and articulate beyond his years, he confronted the microphone.

It struck Alcindor that being so tall made him an easy target.

“I have an announcement to make,” Alcindor said with some reporters underfoot and thrusting recording devices to catch the droplets of words. “This fall I’ll be attending UCLA in Los Angeles.”

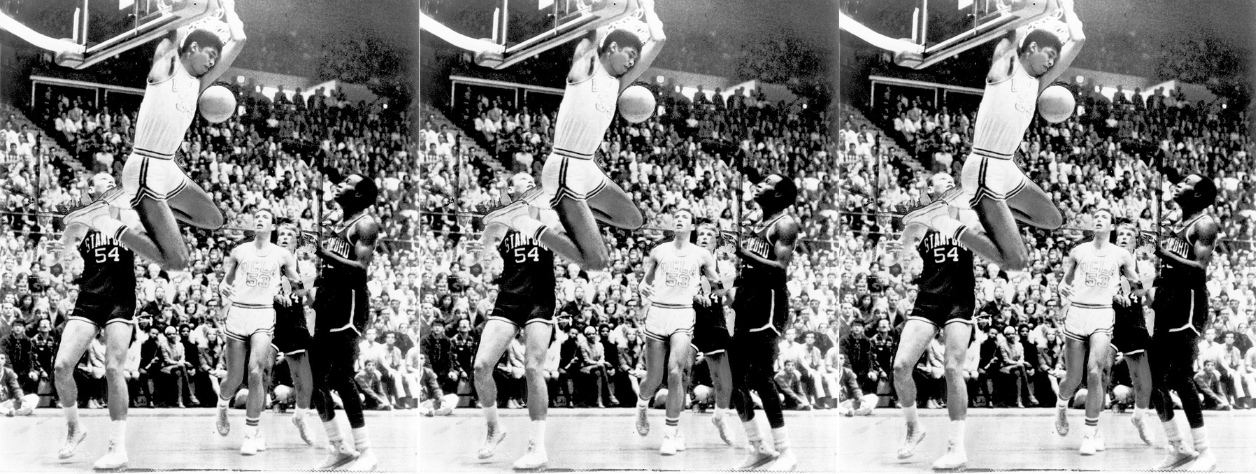

Alarms sounded on wire-service teletype machines in newsrooms out to the West Coast, the ding-ding-ding of a bicycle bell alerted an arriving bulletin ahead of the black-and-white TV images to be beamed across the country. This was historic. Ferdinand Lewis Alcindor Jr. was seven feet, three-quarters of an inch, had scored more points and grabbed more rebounds than any high schooler in a city with a celebrated basketball tradition, and had led Power, an all-boys Catholic school on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, to 71 consecutive victories.

Not only that, UCLA coach John Wooden quickly noted, the recruit was “refreshingly modest and unaffected by the fame and adulation that have come his way, and he plays extremely well at both ends of the floor. His physical size is as much a part of his ability as his team play, hustle, and desire.” The press conference had confirmed as much. Alcindor would rather have been anywhere else, yet handled the announcement with the ease of an experienced politician. Speaking publicly at all was a big deal after the years Alcindor was gladly shielded by his Power coach, Jack Donohue, from the media and the sixty or so colleges that charged to recruit him. The family got an unlisted telephone number and hid behind the curtain.

Even they did not want to step out of line. “Can’t talk anymore, Mr. Donohue said not to say anything,” Cora Alcindor said that morning, just before her son’s lunch-hour announcement. When it finally came time to break the silence, when Alcindor entered the gym in the formal Catholic school uniform to change the course of college basketball forever, he was even allowed to take questions. The decision came later in the academic year than originally anticipated, he responded to one query, because he was “very confused” about whether to stay close to home.

It must have been news to Wooden, who believed Alcindor had committed to UCLA about a month before, at the end of the recruiting visit to Los Angeles. He expects to focus on liberal arts in college. He chose UCLA “because it has the atmosphere I wanted and because the people out there were very nice to me.” No, he replied to another, apparently serious question, there are no liabilities to being tall in basketball.

In Los Angeles, UCLA athletic director J. D. Morgan, holding back his glee, pronounced the university “tremendously pleased” and added, “Of course, this is the boy’s announcement. By the rules of our conference we are not permitted to announce such enrollments.” The hype machine cranked up coast to coast, from the pulsing media market of the East to the publicity center in the West. “His high school press clippings make Wilt Chamberlain and Bill Russell look like YMCA athletes,” John Hall wrote the next day in the Los Angeles Times. “His final decision was awaited with more mystery and fanfare than the word on the first trip to the moon. The pressure on him here will be tremendous.”

Except pressure was nothing new, and a white columnist in his late thirties and twenty-five hundred miles away knew nothing about the scrutiny Alcindor had been living under. It wasn’t grand UCLA, with national championships in 1964 and ’65, the latter only six weeks before his announcement, but New York basketball had its own challenges. The longer the Power win streak went, the more the school and its star center became a target for opposing teams, for media, and for the public. The spotlight went from bright to searing to loathsome as sportswriters made victory a foregone conclusion and Alcindor lost the joy of playing before he left high school. He was eighteen and already burdened by success.

Plus, the racism. Alcindor entered Power the same year the Freedom Riders began in the Deep South and he followed developments as protesters, white and black, put themselves at risk to desegregate interstate buses. When his parents sent fifteen-year-old Lew to North Carolina on a Greyhound in April 1962 to attend the high school graduation of the daughter of a family friend, his body wedged into an aisle seat for the six-hundred-mile ride, Alcindor saw for himself: the whites only signs of the Jim Crow era around restaurants, drinking fountains, and restrooms as the Greyhound reached Virginia and rolled farther south. Even the businesses he saw along the way. Johnson’s White Grocery Store. Corley’s White Luncheonette. Scared and conspicuous—tall, even for an adult, and black—he felt the need to ask local blacks, “Are you allowed to walk on the same side of the street as white people?”

It felt like being in a different country. Alcindor read about lynchings from his parents’ subscription to Jet magazine. The anger from hearing about four girls, none older than fourteen, being killed in a bomb blast while attending a Bible class in a church in Birmingham, what the FBI later said was an act of the Ku Klux Klan, boiled inside him for months. His stomach clenched in fear as he waded into the dangerous world and pushed Alcindor to wonder if he would be hacked to death during the ride. He couldn’t help but think of Emmett Till, murdered at fourteen while visiting Mississippi.

His own coach at Power, the same Jack Donohue who portrayed himself as Alcindor’s protector, left Lew emotionally scorched as a junior in early 1964 with a halftime rant. As Power led a weak opponent by only 6 points with a 46-game winning streak on the line, a frustrated Donohue pointed at his star and shouted about not hustling, not moving, not doing any of the things Alcindor is supposed to be doing, how “You’re acting just like a nigger!” Donohue initially spun the furnace blast of racism into good coaching, telling Alcindor after the victory it had been a motivational ploy, and a successful one at that, and down the line would say Lew misunderstood or deny making the comment at all.

Alcindor began to find his public voice when he joined the newspaper for the Harlem Youth Action Project in 1964. He covered a Martin Luther King Jr. press conference when the preacher came to New York, listening intently while standing in the third row of people behind King. That same year, seventeen-year-old Alcindor worked a fourth consecutive summer at Friendship Farm, a camp run by Donohue in upstate New York, teaching basketball to eleven- and twelve-year-olds out of obligation to his coach while mostly wishing he were somewhere else.

In the months before his senior season of high school, Alcindor again planned to drop the job to focus on work that inspired him, as sports editor of the newspaper for a New York youth organization, only to be guilted into another trip to Friendship Farm when Donohue admitted using Lew’s name to attract customers. Absentmindedly doodling in the dirt with a stick one day, his mind adrift with a world spinning wildly out of control, Alcindor looked down to see what he had scratched in the earth: death to the white man.

A week after returning from Friendship Farm in July 1964, a year before his UCLA decision, riots swept eight blocks of Harlem and Bedford-Stuyvesant after an off-duty police officer fatally shot fifteen-year-old James Powell. The cop claimed the shooting was a reaction to being attacked by Powell with a knife, but about a dozen witnesses countered the white lieutenant had gunned down the unarmed black ninth-grader.

Back in the city from the beach on a hot, muggy Sunday, Alcindor got off the subway to browse jazz records before meeting friends, stepped from 125th Street station and face-to-face with chaos. Looting, smashing windows, cops swinging nightsticks, and flying bullets overwhelmed his senses. Unsure where the shots were coming from and with few options for taking cover, Alcindor did his best to crouch behind a lamppost as people ran past. He stood in shock, frozen except for a slight trembling, until he snapped out of the trance and took off in a dash for safety, thinking only that he wanted to stay alive.

Finally finding sanctuary, “I sat there huffing and puffing, absorbing what I’d seen, and I knew it was rage, black rage. The poor people of Harlem felt that it was better to get hit with a nightstick than to keep on taking the white man’s insults forever. Right then and there I knew who I was and who I had to be. I was going to be black rage personified, black power in the flesh. I was consumed and obsessed by my interest in black power, black pride, black courage.”

It struck Alcindor that being so tall made him an easy target. He wanted to throw a brick, partly for the lieutenant who shot Powell, partly for the racist approach of Donohue, and partly for white teachers at Power “who didn’t think it important to teach us about anyone with a black face.” Alcindor decided against retaliating. Instead, he went to the office of the youth group’s newspaper office and helped put out a special issue on the riot, “chronicling for history what the white media was ignoring. While they were busy tabulating the property damage and police injuries, we were tabulating the cost to the community, to individuals’ spirits, to the hope of easing racial tensions.” Interviewing residents who lived through the flashpoint, he felt their pain and related all too well to the suffering.

The memory of the halftime language…stormed back into Alcindor’s consciousness as he stood in the middle of the Harlem riot.

It took only until his senior year at Power for Alcindor, his insides churning, to become a “very bitter young man, and angry with racism.” No longer was New York a place of youthful innocence, where he started going to Madison Square Garden regularly as a seventh-grader, learning winning basketball by watching Bill Russell when the Celtics visited, admiring the way Russell played for his teammates with rebounding and passing while being a menace defending the basket.

It didn’t feel insular anymore, as it had for so long in the Dyckman Street projects in Inwood, the multiethnic neighborhood at the northern peninsula of Manhattan, with the Hudson River to the west and the Harlem River to the east. Alcindor’s father, Ferdinand Sr., a stern man of six foot three and two hundred pounds known as Big Al, was a police officer with the New York Transit Authority with a musicology degree from prestigious Juilliard and handed down his passion for jazz to his son. Along with his mother, Cora, a seamstress, Alcindor’s parents made education and manners a priority. The home was filled with books and magazines and music and they decided their only child would always attend Catholic schools with the belief they were the best in the city.

The only child had the solitude of his own room in Dyckman from three years old through high school, a rarity among his friends. Yet he was a teenager thirsting for freedom from the mother he found overbearing and a distant father who would go days without talking to Lew, sometimes opening a book wide across his face to avoid eye contact with his son longing for a relationship. Arguably the greatest player in the history of the sport from high school through college and the pros would in retirement remember playing basketball with Big Al once. He wanted out.

Alcindor narrowed his college choice to Michigan, Columbia, St. John’s, and UCLA. He liked Columbia as the chance to attend school walking distance to Harlem and a subway ride to the jazz clubs he had to leave early as a high schooler to make curfew. And making it in the Ivy League would send the message of Alcindor as more than a brainless jock. But the program consistently lost and he wanted to win, not build. St. John’s had the lure of Joe Lapchick, a coach Alcindor respected professionally and liked personally—Alcindor had been friends with Lapchick’s son since eighth grade and was a frequent visitor to the Lapchick home. The school was forcing Lapchick into mandatory retirement, though, removing the biggest appeal for Alcindor. When St. John’s also attempted to hire Donohue as an assistant, likely in hopes of a Power package deal, the school, clearly unaware of Alcindor’s bond with Lapchick and broken relationship with Donohue, had deeply wounded itself for years to come.

President Lyndon Johnson, a Texan, wrote on behalf of the University of Houston and its emerging program. Holy Cross, in some coincidence, hired Donohue as head coach in April, topping the St. John’s opportunity, but Donohue’s star from Power gave only a courtesy campus visit and did not seriously consider continuing the relationship. The memory of the halftime language, coaching strategy or not, stormed back into Alcindor’s consciousness as he stood in the middle of the Harlem riot the following summer. While he would always praise Donohue for helping develop his game, Lew had no interest in more time together.

The decision came down to St. John’s, soon to hire Lou Carnesecca as head coach, or UCLA. Alcindor felt an early connection with Wooden, albeit not to the same extent as with Lapchick, and no bullets had ever whizzed past his head in California. One was in Queens, a borough east of Manhattan, close enough to imagine Cora as a constant presence in his life at a time he wanted to escape the grip of parental oversight. The other was a continent away. So, UCLA.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Kingdom on Fire: Kareem, Wooden, Walton, and the Turbulent Days of the UCLA Basketball Dynasty by Scott Howard-Cooper. Copyright © 2024 by Scott Howard-Cooper. Reprinted by permission of Atria Books, an imprint of Simon & Schuster.

Scott Howard-Cooper

Scott Howard-Cooper has covered professional and college sports since the 1980s for some of the most prominent outlets in the country, including the Los Angeles Times, Sports Illustrated, ESPN, and more. His work has earned multiple national awards from the Associated Press Sports Editors and the Professional Basketball Writers Association for projects, game coverage, features, and columns. He graduated from USC with a degree in political science and lives in northern California.