How Leo and Gertrude Stein Revolutionized the Art World

Miles J. Unger on the Early Patrons of Picasso and Matisse

Matisse and Picasso then being introduced to each other by

Gertrude Stein and her brother became friends but they were enemies.

–Gertrude Stein, The Autobiography of Alice B. Tolkas

If Picasso and Matisse were rivals from almost the first moment each knew of the other’s existence, the contest was driven as much by those cheering from the sidelines as by their own considerable egos. It was Montmartre versus the Latin Quarter, the bande à Picasso versus the Fauves, the dark voodoo of the Spaniard versus the Apollonian grace of the Frenchman. For the most part the competition was respectful, but it could occasionally devolve into childish stunts. Shortly after the exhibition of Joy of Life, a few members of Picasso’s gang went around Montmartre altering posters warning of the dangers of lead paint to read “‘Painters stay away from Matisse!’ . . . ‘Matisse drives you mad!’” And while Matisse generally tried to rise above the fray, on more than one occasion he was overheard making disparaging remarks about Picasso’s art that found their way into the newspapers.

Much of the blame for the fraught situation belongs to an American family recently settled in Paris, three siblings and one spouse from Oakland, California, who were about to establish themselves as the world’s foremost patrons of the avant-garde. The ambitions and peculiar internal dynamics of this clan drew the two artists together, but also thrust them into direct competition. “[Leo] Stein can see at the moment only through the eyes of two painters, Matisse and Picasso,” wrote Apollinaire of those early days, a situation that guaranteed the two leaders of the avant-garde would regard each other with a certain wariness. This was true even before harmony in the Stein family gave way to bickering and mutual recrimination. Then, like children in a messy divorce, the artists were pitted against each other, caught up in a tug of war that made aesthetic judgment a test of personal loyalty.

The Steins—Michael and his wife, Sarah (or Sally), Leo, and Gertrude—were Americans of German Jewish extraction. As children they had enjoyed a peripatetic existence, moving from Baltimore to Vienna to Paris and then back again, finally landing on the far western fringes of the continent in the still frontier-like town of Oakland, California. Here their father, Daniel, appeared to prosper for a time as an executive of the Omnibus cable car company. But when Daniel died unexpectedly, the eldest brother, Michael, discovered that their father was deeply in debt. Taking it upon himself to retrieve the family fortune, he worked his way up to an executive position in the Central Pacific Railroad, raising his brilliant but impractical younger siblings and providing them the means to pursue their own idiosyncratic destinies.

Growing up, Leo and his younger sister Gertrude were inseparable. Physically they were opposites—he spare and willowy, she squat and massive—but when it came to the life of the mind they were kindred spirits. Smarter and more cosmopolitan than their unsophisticated schoolmates, they were thrown back on each other’s company, living in their own world far removed from the concerns of their neighbors. Their sense of isolation was exacerbated by their Jewish heritage, which made them seem exotic and in Leo’s case contributed to a lifelong defensiveness that showed through in verbal torrents that were intended to overwhelm listeners with his brilliance. “Had it not been for the shadow of himself, his constant need of feeling superior to all others,” wrote his friend Hutchins Hapgood, “he would have been a great man.”

When Leo headed to Harvard in 1893, Gertrude followed, enrolling the following year in the Harvard Annex (later renamed Radcliffe, sister school to the all-male university). There she studied with, among others, William James, the foremost philosopher and psychologist of the age. She was much taken with the charismatic professor and he with her, impressed by her intelligence and originality of mind. James’ exploration of the “stream of consciousness” influenced the distinctive prose style Gertrude invented to capture the fleeting perceptions of an eternal present, and his belief in her gifts contributed to her growing conviction that she was destined for greatness.

“It was not simply a matter of buying a particular work—which, after all, was not that expensive—but of placing a bet on the future of art, one made in the face of widespread ridicule and in defiance of conventional wisdom.”

Like Leo, Gertrude was bright but undisciplined. She pursued intellectual enthusiasms but dropped them when the initial impetus was lost. After a somewhat uneven career at Harvard, she followed Leo to Johns Hopkins, where she enrolled in the medical school, only to lose interest after a few months. When one of her fellow students urged her to apply herself, not only for her own sake but for the cause of women’s rights, Gertrude sighed, “You don’t know what it is to be bored.”

By this time Leo had left Johns Hopkins to study art in Florence. The two Stein siblings were well on their way to becoming professional dilettantes, gifted but erratic, decidedly unconventional, and indulged in their eccentricities by their older brother, who was willing to fund their somewhat aimless intellectual journey. For Gertrude, the discovery of her unconventional sexuality further distanced her from more straitlaced peers, leaving her ever more determined to chart her own course. An early short story, “Q.E.D.,” unpublished during her lifetime, is based on her unhappy affair with the feminist editor Mary “May” Bookstaver.

In the wake of this failed romance, Gertrude rejoined Leo, first in Florence and then in England. By this time Leo had come under the influence of a scholar and fellow Harvard alum, Bernard Berenson, who encouraged him to apply his talents to art history. He briefly contemplated a book on the Renaissance artist Andrea Mantegna but dropped the project when he discovered that two other scholars were already preparing works on the painter.

In the summer of 1903, Leo moved to Paris, renting an apartment at 27 rue de Fleurus in Montparnasse, a couple of blocks west of the Jardin du Luxembourg. Gertrude joined him later that fall. Here in this middle-class neighborhood, in an apartment decorated with Renaissance furniture acquired in Florence and the Japanese prints that Leo had begun to collect, brother and sister set up their household together, each of them casting about for some purpose in life commensurate with their scattershot abilities.

Now 31, Leo had yet to find direction. His latest ambition to become a painter fared no better than his previous enthusiasms. “Art,” he complained to his friend Mabel Weeks, “is having its revenge on me.” Gertrude was only a bit more focused; she’d decided that becoming a writer was the surest route to la gloire, as she called it, but had yet to discover the singular approach to language that would make her one of the distinctive literary voices of the 20th century.

While Gertrude was finding her vocation, her older brother was discovering the one area in which his peculiar combination of talents—a keen but unfocused mind, strong opinions pugnaciously expressed, aesthetic insight unredeemed by any actual talent, and a need to prove himself smarter than anyone else in the room—could flourish. Oddly, it was Berenson, the world’s foremost authority on Renaissance art, who introduced Leo to the painting of Cézanne and set him on the path to becoming a collector of modern art. “Do you know Cézanne?” Berenson asked him after Leo complained that there was nothing to see in Paris. “I said I did not. Where did one see him? He said, ‘At Vollard’s’; so I went to Vollard’s and I was launched.”

One reason Leo Stein decided to collect modern art was that he simply couldn’t afford to buy the old masters. The Steins were prosperous compared to the artists they would soon be collecting, but comfortably middle class rather than wealthy. Buying art, Leo had always assumed, was a hobby for the rich, but when he realized he could afford work created by his contemporaries, he claimed he felt “a bit like a desperado . . . One could actually own paintings even if one were not a millionaire.” Vollard, for his part, enjoyed doing business with the Steins, since, as he explained to Leo, he was one of the few who bought pictures not because he was rich but despite the fact that he wasn’t.

Cézanne was the artist who first got Leo excited about modern art, and he and Gertrude spent hours rummaging through the dusty old stacks that Vollard stowed away in his cluttered gallery. In these early days of their collecting it was Leo who led the way, with Gertrude deferring to her brother’s discerning eye and greater knowledge.

By that time Michael and Sally had also arrived in Paris. Though not a born bohemian like Leo and Gertrude, Michael, encouraged by Sally, who wanted to study art, had apparently decided that the carefree lifestyle of his two younger siblings was far more attractive than his plodding nose-to-the-grindstone existence. The couple, along with their young son, Allan, took an apartment on the rue Madame, around the corner from Leo and Gertrude, and the reunited Stein family prepared to sample all the intellectual and aesthetic delights the City of Light had to offer.

*

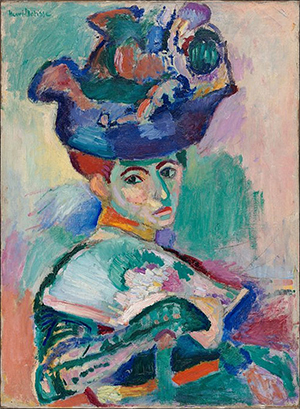

It would be difficult to overestimate the audacity of the Stein family when they decided to purchase Matisse’s portrait of his wife, listed in the catalogue as Woman with a Hat. It was not simply a matter of buying a particular work—which, after all, was not that expensive—but of placing a bet on the future of art, one made in the face of widespread ridicule and in defiance of conventional wisdom. For the family as a whole, and for Leo in particular, this was part of the attraction. They reveled in the thrill that comes from doing something illicit. By purchasing the notorious canvas, they would be bringing into their home not an object of timeless beauty but something that pulsed with an almost toxic energy, insidious, radio-active, transformative.

Woman with a Hat, Henri Matisse, 1905

Woman with a Hat, Henri Matisse, 1905

It’s not entirely clear which member of the Stein family deserves the credit for “discovering” Matisse. According to Leo’s account, he’d had his eye on the artist since the Salon d’Automne of 1904, when Matisse’s Luxe, Calme et Volupté made on him “the strongest impression, though not the most agreeable.” Around that time he stopped by Berthe Weill’s gallery, where the proprietor tried to interest him in the painter’s work. Leo declined, and Weill herself later admitted “the paintings weren’t ripe yet.” It was only the following year, when, in the company of his sister, brother, and sister-in-law, he saw Woman with a Hat, that he realized he was in the presence of “something that was decisive.” Recalling the impact of the work on him decades later, after he had largely given up on modern art and the rest of the Stein clan had chosen sides—Michael and Sally opting for Matisse, Gertrude faithful to Picasso, Leo deciding he’d had enough of both—he managed to pat himself on the back for his perspicacity while at the same time revealing an ambivalence and the infuriating condescension that was an essential part of his nature. “It was a tremendous effort on his part,” Leo wrote, “a thing brilliant and powerful, but the nastiest smear of paint I had ever seen. It was what I was unknowingly waiting for, and I would have snatched it at once if I had not needed a few days to get over the unpleasantness of the putting on of the paint.”

Thérèse Jelenko, a family friend, suggested that it was in fact Michael and Sally Stein who first perceived the brilliance of the much reviled canvas. “I still can see Frenchmen doubled up with laughter before it,” Jelenko recalled, “and Sarah [Sally] saying ‘it’s superb’ and Mike couldn’t tear himself away.” Matisse later confirmed Sally Stein’s vital role, claiming she was the one “who had the instinct in that group.” Whoever made the first move, what is beyond dispute is that these peculiar Americans had a far keener appreciation of the most radical art than their French peers. While Parisians jeered, the Steins pooled their resources and snatched up the painting.

Matisse, who’d been shaken by the almost universal condemnation, was almost equally shocked when he heard the painting had found a prospective buyer. Soon Woman with a Hat was hanging in the pavilion at 27 rue de Fleurus, the large room in the courtyard that had served as Leo’s atelier until he concluded he was too neurotic to make it as a painter. Alongside his Renaissance furniture, his Japanese prints, and even his Cézannes, the Matisse struck a decidedly dissonant note. But its power to shock was exactly what appealed to Leo. Matisse was now the most talked about artist in Paris, widely scorned as the demented leader of a band of anarchists who wished to tear down everything good Frenchmen held sacred. By backing this subversive, Leo made sure he was part of the conversation.

In purchasing the work Leo was staking his own claim to originality. What distinction was there in collecting a work that consensus had already anointed a masterpiece? Only by seeing what others couldn’t, by singling out for praise what the great mass of men and women despised, could he fulfill his ambition. As his collection grew, and as its fame spread, Leo was in his element, bestowing enlightenment like a Buddhist sage on those who made the pilgrimage to the temple dedicated to the adventurous spirit of modernism he was building. “People came,” he said, “and so I explained, because it was my nature to explain.”

Ultimately the artists would disappoint him: he purchased his last Matisse in 1908, his last Picasso two years later. Neither of his most important discoveries would allow himself to be led by his theories, so he abandoned them; and once they became household names, there was no longer any credit in singing their praises. He retreated into cranky old age, outliving his gifts and his courage, grumbling that the world no longer listened to him.

But for a few crucial years he was the most daring prophet of the new. His eventual apostasy should not diminish the pioneering role he played in these early years in promoting art that most still regarded as a threat to the established order. If Leo was dogmatic, pompous, and perhaps even a bit deranged, no one could deny that he had courage and that his financial and rhetorical support came at a critical time for the modernist movement, when powerful forces were determined to smother the dangerous new tendencies in the cradle.

Indeed, Leo Stein saw himself as more than simply a collector: he was a patron in the mold of the great Renaissance princes—the d’Este, the Medici, the Montefeltri—who acquired immortal fame through their enlightened support of the greatest talents of the age. In addition to Matisse, Leo cast about for other worthy souls to champion. His search inevitably took him to Montmartre and to the various junk shops–cum–galleries that clustered in the vicinity of the Butte. “It was a queer thing in those days that one could live in Montparnasse and be entirely unaware of what was going on in the livelier world of Montmartre,” he said. “I was a Columbus setting sail for a world beyond the world.”

__________________________________

From Picasso and the Painting that Shocked the World. Used with permission of Simon & Schuster. Copyright © 2018 by Miles J. Unger.

Miles J. Unger

Miles J. Unger writes on art, books, and culture for The Economist. Formerly the managing editor of Art New England, he was a contributing writer to The New York Times. He is the author of The Watercolors of Winslow Homer; Magnifico: The Brilliant Life and Violent Times of Lorenzo de’ Medici; Machiavelli: A Biography; and Michelangelo: A Life in Six Masterpieces. His most recent book is Picasso and the Painting That Shocked the World.