How Lee Krasner Made Jackson Pollock a Star

Along with the Emerging Art Critic Clement Greenberg

Jackson’s January 1947 exhibition at Peggy’s Art of This Century sold well, but it would be his last with her before she left for Venice in May.[24] In her wake, it was difficult to find a gallery willing to show him. In addition to his art, into which Jackson began to insert cigarette butts, coins, tacks, string, and sand, there was the problem of his drinking.[25] As a result, the very, very few gallery owners who handled avant-garde work were unprepared to take a chance on him. In 1946, however, a finishing school graduate whose aristocratic family owned homes in New York, Newport, and Palm Beach, had opened a gallery on 57th Street, and she was brave enough to give Jackson a try.[26]

On paper, there would not have been a less likely candidate to enter a relationship with Pollock than Betty Parsons. Betty, however, was neither a bluestocking nor a businesswoman. Betty was a sculptor who was “born with a gift for falling in love with the unfamiliar,” she said. “Actually, being an artist gave me a jump on other dealers—I saw things before they did. Most dealers love the money. I love the paintings.”[27] Betty and painter Barney Newman, who advised her, went to Springs to meet with Jackson and Lee. “At one point he sat on the floor and made a beautiful drawing for me which I call the Ballet of the Insects—it’s so alive!” Betty recalled of Jackson. “I was fascinated and told him I would like to have him.”[28] Jackson agreed.

Betty’s was not the only new gallery in town. The scene on 57th Street was changing. After the war, Americans were flush with cash but had no place to spend it because the industries that produced the consumer goods people craved had not yet been fully reconverted to civilian purposes. So, while waiting to buy that new car or refrigerator, some had decided to spend a few dollars on art. When asked why he and others collected, one Wall Street broker said, “It’s just a fad . . . like those miniature golf courses.”[29] Of course, there was more to it than that. During the war, the patriotic programs at museums had attracted new audiences. Museums began to be viewed as American institutions, not mausoleums for dead Europeans or warehouses of artifacts. The Museum of Modern Art was even rated the fourth most popular tourist attraction in a survey of soldiers on leave from the military.[30]

Amid that increased attention, 1945 would be a banner year for gallery sales, and while the majority of art sold was European, or American versions of European art, a few adventurers purchased paintings by artists working in New York. They were new collectors, generally under the age of 45, who sensed something was happening and wanted to “get in on the ground floor.”[31] The galleries in the city that showed the art they sought, however, numbered only about four. It was just too risky financially to build a business on bold American work. And if galleries were reluctant to show the avant-garde New York men, they were loath to show avant-garde New York women. (Gallery owner Sam Kootz said he would never show women because “they were too much trouble.”) To collectors, and therefore to the dealers who depended upon them, “genius” was a word that could only be applied to a man.[32]

Women who had worked in New York in equality and obscurity beside their male colleagues since the Project had had a preview of the changing perception of women as artists with the arrival of the Surrealists, who revered and objectified them to better contain and control them. Some American men had adopted that attitude, but it hadn’t pervaded the scene or had any tangible impact other than as an annoyance. Personal sexism could not keep an artist from expressing herself. Institutional bias on the part of galleries and museums, however, could. It would impede a woman’s ability to show her work, and that would create a caste system: professionals who exhibited, and amateurs who did not, with women consigned to the disenfranchised latter category. The critic who reviewed sculptor Louise Nevelson’s first major show unabashedly illustrated the official art world’s reaction to women: “We learned that the artist was a woman in time to check our enthusiasm. Had it been otherwise, we might have hailed these sculptural expressions as by surely a great figure among the moderns.”[33] In that environment, it would take a woman made of tough stuff to continue. It seemed that the wider the art world grew, the fewer the opportunities for women in it. That meant that just as Lee began producing her best paintings, her hopes of exhibiting diminished. And still she persisted.

I couldn’t run out and do a one-woman job on the sexist aspects of the art world, continue my painting, and stay in the role I was in as Mrs. Pollock. I just couldn’t do that much. What I considered important was that I was able to work . . . You have to brush a lot of stuff out of the way or you get lost in the jungle.[34]

Lee was not alone. Life for an artist, any artist, was difficult. There were few rewards other than the most important, which was satisfying one’s need to create. But in the art world of galleries, collections, and museums that the New York artists would inherit in the late 1940s, the difficulties experienced by the men who painted and sculpted would be nothing compared to those of the women. They had to fight with every fiber of their being not to be completely ignored.[35] In a treatise published at the start of the war, author Pearl S. Buck wrote,

The talented woman . . . must have, besides their talent, an unusual energy which drives them . . . . Like talented men, they are single-minded creatures, and they cannot sink into idleness, nor fritter away life and time, nor endure discontent. They possess that rarest gift, integrity of purpose. . . . Such women sacrifice, without knowing they do, what many other women hold dear—amusement, society, play of one kind or another—to choose solitude and profound thinking and feeling, and at last final expression.

“To what end?” another woman might ask. To the end, perhaps . . . of art—art which has lifted us out of mental and spiritual savagery.[36]

Lee was that single-minded woman whose focus was art. But the art that preoccupied her was her own and her husband’s. She lived and worked for two people, which was a natural course for a woman of her temperament and generation to take. Beginning with Elaine de Kooning, however, some of the younger women coming after Lee—daughters of another time—would refuse to accept a similar place in the relative shadows. As much as they may have respected her, Lee would become an example of what they would not do. The New York art world was teeming and vibrant, the conversation scintillating, the work being produced wonderfully unexpected. They wanted to be part of it and, no matter the cost, would demand to be heard.

*

[1] Clement Greenberg, “The Situation at the Moment,” Partisan Review 15, no. 1 (January 1948), 82.

[2] Florence Rubenfeld, Clement Greenberg: A Life (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2004), 44, 50; Lee Krasner, interview by Barbara Novak, videotape courtesy Pollock-Krasner House and Study Center.

[3] Rubenfeld, Clement Greenberg, 31, 33–34, 41, 43, 44, 97, 144; Caroline A. Jones, Eyesight Alone: Clement Greenberg’s Modernism and the Bureaucratization of the Senses (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2005) 31; Deborah Solomon, notes on Clement Greenberg based on interview, December 19, 1983, Series 1, Box 1, Folder 2, the Clement Greenberg Papers, 1937–1983, Archives of American Art-Smithsonian Institution, 1; oral history interview with Harold Rosenberg, Archives of American Art-Smithsonian Institution.

[4] Rubenfeld, Clement Greenberg, 32, 37, 41, 43, 50; Jones, Eyesight Alone, 5, 23, 31, 267, 277.

[5] Rubenfeld, Clement Greenberg, 42–44, 50; Norman L. Kleeblatt, ed., Action/Abstraction: Pollock, De Kooning, and American Art, 1940–1976. The Jewish Museum, New York, May 4–September 21, 2008. (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2008), 143; Dore Ashton, The Life and Times of the New York School (Bath, Somerset, UK: Adams & Dart, 1972), 79– 80; Jones, Eyesight Alone, 267, 277.

[6] Clement Greenberg, “Avant- Garde and Kitsch,” Partisan Review 6, no. 5 (Fall 1939): 37– 41, 44; Rubenfeld, Clement Greenberg, 51– 52, 78; Jones, Eyesight Alone, 22.

[7] Greenberg, “Avant- Garde and Kitsch,” 37–40.

[8] Ibid., 46–48.

[9] Clement Greenberg, “Art,” The Nation, April 7, 1945: 397–98; Kirk Varnadoe with Pepe Karmel, Jackson Pollock (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1998), 42; Elaine de Kooning, interview by Jeffrey Potter, courtesy Pollock-Krasner House and Study Center. Elaine said Clem acted as “an unpaid PR man. It came from his heart’s blood. He meant every word of it, but he performed services for Jackson. Period.”

[10] Rubenfeld, Clement Greenberg, 78, 91.

[11] Deborah Solomon, Jackson Pollock: A Biography (New York: Cooper Square Press, 2001), 153; Jones, Eyesight Alone, 261.

[12] Clement Greenberg, interview by James Valliere, Archives of American Art-Smithsonian Institution.

[13] Deborah Solomon, notes on Clement Greenberg, based on interview, December 19, 1983, Series 1, Box 1, Folder 2, the Clement Greenberg Papers, 1937– 1983, Archives of American Art-Smithsonian Institution, 3.

[14] Steven Naifeh and Gregory White Smith, Jackson Pollock: An American Saga (New York: Clarkson N. Potter, Inc., 1989), 528; Natalie Edgar, ed. Club Without Walls: Selections from the Journals of Philip Pavia (New York: Midmarch Arts Press, 2007),45.

[15] Geoffrey Dorfman, ed. Out of the Picture: Milton Resnick and the New York School (New York: Midmarch Arts Press, 2003), 58.

[16] Lee Krasner: An Interview with Kate Horsfield, videotape courtesy Pollock-Krasner House and Study Center.

[17] Lee Krasner, interview by Barbaralee Diamonstein, provided by Dr. Barbaralee Diamonstein-Spielvogel, interviewer and author, from Inside New York’s Art World (New York: Rizzoli International Publications, Inc., 1979), 210; Barbara Rose, “Jackson Pollock at Work,” Partisan Review 47, no. 1 (Winter 1980): 86.

[18] Ellen G. Landau, “Lee Krasner’s Early Career, Part Two: The 1940s,” Arts Magazine 56, no. 3 (November 1981): 82–83; Ellen G. Landau, Lee Krasner: A Catalogue Raisonné (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1995), 106; Robert Hobbs, Lee Krasner (New York: Abbeville Press Publishers, 1993), 42.

[19] Lee Krasner, interview by Barbara Novak, videotape courtesy Pollock-Krasner House and Study Center.

[20] Cindy Nemser, “A Conversation with Lee Krasner,” Arts Magazine 47, no. 6 (April 1973): 44.

[21] Landau, Lee Krasner: A Catalogue Raisonné, 115.

[22] Nemser, “A Conversation with Lee Krasner,” 44.

[23] Gail Levin, Lee Krasner, A Biography (New York: William Morrow, 2012), 20, 245–46; Landau, Lee Krasner: A Catalogue Raisonné, 230; Robert Hobbs, Lee Krasner (New York: Independent Curators International, with Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1999), 72; Eleanor Munro, Originals: American Women Artists (New York: A Touchstone Book, Simon & Schuster, Inc., 1982), 105.

[24] Naifeh and Smith, Jackson Pollock, 544.

[25] Donald Hall and Pat Corrington Wykes, eds. Anecdotes of Modern Art: From Rousseau to Warhol (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990), 329.

[26] Aline B. Louchheim, “Betty Parsons: Her Gallery, Her Influence,” Vogue (October 1, 1951): 194; Lee Hall, Betty Parsons: Artist, Dealer, Collector (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1991), 18, 20, 25, 77.

[27] Oral history interview with Betty Parsons, June 4 and June 9, 1969, Archives of American Art-Smithsonian Institution; Hall, Betty Parsons, 36, 171.

[28] Jeffrey Potter, To a Violent Grave: An Oral Biography of Jackson Pollock (Wainscott, NY: Pushcart Press, 1987), 91.

[29] Russell Lynes, The Tastemakers: The Shaping of American Popular Taste (New York: Dover Publications, 1980), 256–57; John Patrick Diggins, The Proud Decades: America in War and Peace, 1941–1960 (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1988), 98–99; Read, The Politics of the Unpolitical (London: Routledge, 1945), 47–48.

[30] Alice Goldfarb Marquis, Alfred H. Barr, Jr., Missionary for the Modern (Chicago: Contemporary Books, 1989), 228.

[31] ArtNews, 43, no. 9 (July 1944): 14, 23.

[32] Rozsika Parker and Griselda Pollock, Old Mistresses: Women, Art and Ideology (London: Pandora, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers, 1981), 114; Thomas B. Hess and Elizabeth C. Baker, Art and Sexual Politics: Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists? (New York: ArtNews Series, Collier Books, 1973), 57; Ann Eden Gibson, Abstract Expressionism: Other Politics (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1997), 22.

[33] Kleeblatt, Action/Abstraction, 17; Oliver W. Larkin, Art and Life in America (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1949), 465.

[34] Cindy Nemser, Art Talk: Conversations with 12 Women Artists (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1975), 91.

[35] Gibson, Abstract Expressionism, 142.

[36] Pearl S. Buck, Of Men and Women (New York: The John Day Company, 1941), 76–77.

__________________________________

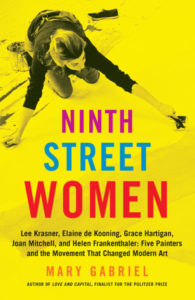

From Ninth Street Women: Lee Krasner, Elaine de Kooning, Grace Hartigan, Joan Mitchell, and Helen Frankenthaler: Five Painters and the Movement That Changed Modern Art. Used with permission of Little, Brown and Company. Copyright © 2018 by Mary Gabriel.

Mary Gabriel

Mary Gabriel worked in Washington and London as a Reuters editor for nearly two decades. She is the author of Love and Capital: Karl and Jenny Marx and the Birth of a Revolution, which was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize, the National Book Award and the National Book Critics Circle Award, as well as of Notorious Victoria: The Life of Victoria Woodhull, Uncensored, and The Art of Acquiring: A Portrait of Etta and Claribel Cone. Ninth Street Women is her latest book. She lives in Italy.