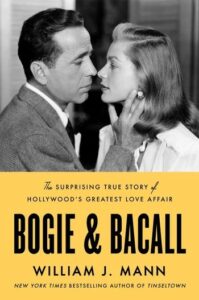

How Lauren Bacall Secured Her Legendary Love Story with Humphrey Bogart

William J. Mann on the Movie Star’s Memoirs

New York City, Late February 2005

“Let’s have the Café Flore today, shall we?” asked Lauren Bacall, grandly laying down coasters from the fabled Parisian coffeehouse. Her maid had just brought out a cozied coffeepot and a couple of cups to the table, where Bacall sat with a writer from the New York Times. The writer thought that Bacall spoke with “an actress’s reflexive flourish.”

The 80-year-old movie star was putting on a show, as she always did when she wanted to impress a visitor. They sat in her living room stuffed with priceless artwork and cheap souvenirs, such as coasters that had value only to her. Beyond them, oversized windows looked down on the cold, bare trees of Central Park. But the temperature in the Dakota, one of New York’s poshest addresses, was just right.

The Times writer had come to interview Bacall about the release of her third memoir, By Myself and Then Some, which everyone expected to sell as well as her first memoir, By Myself, some 27 years earlier. Bacall was pleased to do the interview, but when she learned that the Times was not planning to review the book, she became quite cross. “What the fuck is the Times thinking?” she asked after the writer left; she harshly blamed one of her managers for the newspaper’s decision. The people who worked for her knew that she wasn’t always as gracious in private as she was to important visitors. “She could be lovely, and she could also turn very cantankerous,” said one of her agents, Scott Henderson. “You never knew which one you were going to get.”

The problem many news outlets were having with Bacall’s latest memoir and the reason that so few reviews of By Myself and Then Some had been published was that the new material made up only about one-eighth of the book. The rest was just a reprint of By Myself, which the Times, and countless others, had already reviewed back in 1978.

“When I have a lull in my life,” Bacall told the Times writer, attempting to explain the reasoning behind her latest memoir, “I write, and that’s fairly often.” She was continually struck, she said, by the “fairy-tale life” she had led since she was 19. “Who could have thought something like that could happen?” But, the Times writer noted, her words grew wistful. “Nothing,” Bacall went on, “is ever as good as it is in the beginning.”

Ah, yes, that beginning. Brooklyn teenager Betty Bacal becomes Hollywood love goddess Lauren Bacall. She teaches Humphrey Bogart to whistle and sets the world on fire. At 20, she marries Bogart, who is 25 years her senior and who, in the fullness of time, will be named the greatest movie star in history. “Bogie” and his “Baby” live happily ever after, which means 12 years, during which time they make four successful, iconic films. Then Bogie dies, horribly, of cancer, and their story slips into legend, aided and abetted by Bacall herself. Her post-Bogart life is never the same, never as good.

That had been a hard, cruel truth for the young widow with another 57 years of life ahead of her. “With all the great luck I had,” she told another interviewer, “to have that in my life early on, you know…” Her voice trailed off until she found her words. “For the rest of your life, you just stumble through as best you can.”

She was all too aware that after she was gone, others would put their own spin on the stories she’d told (and not told).The process of stumbling through included writing three memoirs. Over the previous four decades, Bacall had invested a great deal in shaping the legend to her satisfaction. First she had trusted two friendly biographers, Joe Hyams and Nathaniel Benchley, both of whom tried to please her; she wrote the introduction to the first and had the second dedicated to her.

When what Hyams and Benchley came up with didn’t fully satisfy her, she started writing herself. She was all too aware that after she was gone, others would put their own spin on the stories she’d told (and not told). So she made sure to carve as many stone tablets as possible to leave behind. In the various accounts she told about herself and Bogart and their life together, Bacall could be both surprisingly candid and conspicuously disingenuous.

Her candor about some things—Bogie’s last illness, for one—seemed to make her a reliable narrator and distracted readers from the things she had skipped over—such as Bogie’s affair with his hairdresser and the extent of his alcoholism. Bacall’s crafting of the legend was always more about omission than invention. By the time she died in 2014, the mythology of Bogie and his Baby was solidly in place, and it was pretty much of her own design.

Lauren Bacall and Humphrey Bogart were arguably Hollywood’s greatest love story, and maybe not even so arguably. Whose story was greater? Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton? Too chaotic and such an unhappy ending. Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz? Too self-destructive. Clark Gable and Carole Lombard? Poignant and tragic but too brief. Katharine Hepburn and Spencer Tracy? Too much window dressing.

It’s notable that Bacall looked to Hepburn as her model for stardom. Hepburn brilliantly created a mythos about herself, and Bacall clearly took note. She watched as her pal “Katie” orchestrated a veritable cottage industry of mythmaking throughout the 1980s and 1990s (books, articles, interviews, documentary films). Bacall didn’t need to repackage her life with Bogart the way Hepburn had done with Tracy. The Bogart-Bacall relationship was real; it was wonderful; it was passionate; it was complicated. But there were still lessons to be learned from Hepburn that Bacall used in writing and promoting her second and third memoirs.

Like Hepburn, she delivered her story with such imperious authority that no one dared question her version of events. But in so carefully controlling the way her life was chronicled, Bacall narrowed Bogart’s story as much as she did her own. One of the few reviews of By Myself and Then Some, in the Guardian, commented that Bacall’s version of Bogie tended to “blur the man himself.” That does a disservice to a figure that remains such a cultural touchstone, not just the greatest movie star but a prototype for the modern American man.

Humphrey Bogart has come down to us as the supremely confident, unflappable, unpretentious, reluctant movie star, filled with integrity, strength, and disdain for phonies. That’s not untrue. He did have integrity and he did have strength, and he very much disdained phonies, but he was softer than such a description would imply. He was wounded, vulnerable, and filled with self-doubt.

He lived most of his life trying to overcome the emotional deprivations of his childhood. He was no tough kid from the streets, as so many people thought based on the roles he played, but rather the privileged son of a wealthy physician and an acclaimed illustrator. Yet for all his birthright, he never felt he measured up. Denied love by his parents, expelled from schools, fired by employers, he struggled with self-worth all his life. That helps explain the drinking and the rage it unleashed.

But this complex and unguarded Bogart does not appear in Betty’s pages, and consequently he’s largely absent from the public’s memory of him as well. Instead, he is the cynical, hard-edged Sam Spade or Rick Blaine, and his legendary output of film noir classics continues to play in Bogart festivals all over the world. Yet although he brilliantly created Spade and Rick—and Duke Mantee and Philip Marlowe and Mad Dog Earle and Charlie Allnut—from parts of himself, the characters and the man were very much not one and the same.

But in so carefully controlling the way her life was chronicled, Bacall narrowed Bogart’s story as much as she did her own.The real Humphrey Bogart was gentler, more romantic, more yearning than the legend admits. In his youth, he was a Broadway cavalier, a speakeasy dandy, who wanted very much to become a romantic matinee idol. He loved the theater, he loved his craft, and he cared about becoming a better actor, pushing himself to take chances. But the wounded child within him made regular and devastating appearances over the course of his career, and his alcoholism constantly threatened everything he had achieved.

The legend holds that Bacall saved him, that with her Bogart finally found true love and contentment. There’s truth in that, but as always, the truth is complicated. That Bogie and Bacall loved each other is undeniable. But in fact, Bogie had been in love with his first three wives as well, a fact deliberately obscured and sometimes denied in service to the Bogie and Bacall legend.

Each time he wed, Bogie thought he’d found true love. Turns out, the cynical, hard-hearted Humphrey Bogart was a softie when it came to love. He was no philanderer. His friend John Huston, who most definitely was, often remarked that Bogie never chased his leading ladies or starlets on the lot. Instead, he fell for a woman, married her, then hoped to remain true to her. But for the legend to maintain that Bacall was his one and only, that romantic early Bogart had to be played down, and his earlier wives had to be minimized, especially Mayo Methot, whom Bacall replaced.

There is considerable misogyny threaded through the stories, columns, and interviews about Bogie’s life, and much of that has been heaped on Methot, a high-spirited former child star who was turned into a monster by the chroniclers of Bogie’s legend. Joe Hyams set the template for subsequent biographers to use in portraying Methot, even though Hyams hadn’t arrived in Hollywood until 1951, six years after Bogart and Methot divorced. Even Sperber, using Hyams as her source, portrayed Methot as a paranoid schizophrenic. Methot was clearly an alcoholic, but so was her husband. It would be Methot, however, who was left to take the fall for the failure of the marriage. Bogie could not, even partially, be at fault. It was Methot’s drinking that was out of control, not Bogart’s.

By 2005, when his widow began promoting her latest chapter of their story, Bogart had passed into myth. Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless had paid him homage. Woody Allen had built an entire play and then a movie around him with Play It Again, Sam. An actor named Robert Sacchi had made a career as Bogie’s double, starring in The Man with Bogart’s Face as a private investigator who has plastic surgery to look like his idol.

The Brattle Theatre in Cambridge, Massachusetts, has been the nexus of a worldwide “Bogie cult” dating back to the 1950s. In 1997, Entertainment Weekly named Bogart the number one movie legend of all time; two years later, the American Film Institute ranked him the greatest male star (Katharine Hepburn, notably, was the greatest female).

The fundamental mystery is how this particular actor—not conventionally attractive, with a persona honed during depression and war—was able to surpass Clark Gable, Cary Grant, Jimmy Stewart, Marlon Brando, Montgomery Clift, Paul Newman, Warren Beatty, and everyone else to become the greatest movie star of all time. “Immortality is a difficult subject,” the journalist Alyssa Rosenberg wrote. “It doesn’t actually make sense that Humphrey Bogart would endure as a romantic hero when the much handsomer, and much more sexually compelling Clark Gable is largely remembered for his performance in Gone With the Wind … Bogart’s humor was much more bitter and clipped than William Powell’s, whose performances as Nick Charles would seem to have held up better in an age that venerates irony than Bogart’s bitten-off jokes.”

For all her mythologizing, her story is remarkable even without the ornamentation.But Humphrey Bogart embodied America in a way that few other actors managed, not in the loud, garish manner of John Wayne but with a quieter, grounding sense of history. “As an actor,” one critic wrote, “Bogart’s sensibility derives from the Wild West, a lawless, gunslinging world where the code of honor is no antiquated frivolity but an essential chapter in the survivor’s handbook.” (This despite the fact that Bogie was never all that good in western films.)

Bogart was an ordinary Joe who learned how to survive and get what he wanted. He was wounded and guarded, on the borderline of ugly, but extraordinarily self-possessed. He managed to do something few actors achieved. “In a sense, his talent is narrow,” Time magazine opined soon after he won an Oscar for The African Queen. “For all his technical excellence, Bogart never gets completely out of Bogart and into the character he plays. But … few stars can so convincingly and smoothly accomplish the trick of fitting a character to themselves.

In an odd sort of way, as a result, Bogart manages to achieve surprising range and depth while still remaining the familiar figure with whom millions expect to renew an acquaintance when they pay at the box office to see a Bogart film.” That description is the heart of his appeal.

That Bogart lived according to principle and a deep-rooted set of values can be seen in the stand he took against the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1947. Along with Bacall and several others, he traveled to Washington to protest what many saw as unconstitutional infringements on freedom of speech and expression. Though Bogie and Bacall were forced to backtrack in the face of the anti-Communist hysteria that swept the country, they had revealed themselves as persons of conscience. That, too, has served their legend.

The image Bacall worked so hard to codify in the public mind was, in fact, more authentic than many Hollywood stories. She just left out some of the things that made it human. We get very little of what it was like to marry a man a generation older than she was. Love knows no age, of course, but a 25-year age gap has its challenges, and Bacall tells us very little about them. She is also circumspect in how she discusses her involvements with Adlai Stevenson and Frank Sinatra during her marriage to Bogie; as it turned out, Bogart wasn’t the only one being emotionally unfaithful in the marriage.

For all her mythologizing, her story is remarkable even without the ornamentation. Lauren Bacall was one of the great Hollywood survivors. She was lonely in her last years, a regrettable finale that I wished, when writing about it, could have been different. But what a career she’d had! Leaping from movies to the Broadway stage and winning two Tonys for the effort. Blossoming from a sultry siren into a musical comedy star, giving 200 percent of herself during both incarnations. It’s not easy for a beautiful young model to grow old in the public eye. But Bacall did, without apology. She tried Botox once, hated it, and never did it again. “I think your whole life shows in your face and you should be proud of that,” she said.

In 2009, five years before her death, Bacall was awarded an honorary Oscar “in recognition of her central place in the golden age of motion pictures.” The little gold man had proved to be elusive. She hadn’t been nominated until 1996, for The Mirror Has Two Faces. She hadn’t won. Still, as much as she’d wanted it, Bacall didn’t need an Oscar to solidify her status. After her death, as she expected, her obituaries heralded Bogie and Bacall as “Hollywood’s Greatest Love Story.” All her work had paid off. The legend was secure.

What’s still needed is to understand the people behind it.

__________________________

Excerpted from BOGIE & BACALL: The Surprising True Story of Hollywood’s Greatest Love Affair. Copyright © 2023 by William J. Mann. Used with permission of the publisher, Harper. All rights reserved.