In 1910, freshly married to my grandmother, the pharmaceutical heiress Elisabeth Merck, my grandfather Kurt Wolff hitched himself as silent partner to the publisher Ernst Rowohlt, who had just launched what would become one of Germany’s most important houses. With his lean frame and drawing-room manners, now installed in a Leipzig apartment with household help, Kurt cut a starkly different figure from Rowohlt, a bluff and earthy character who would conduct business in taverns and wine bars around town and sometimes sleep in the office. By June 1912, having abandoned his doctoral work, Kurt found more time to stick his nose into the affairs of the publishing house. Thus he was in the office the day Max Brod, a writer from Prague, turned up with a protégé named Franz Kafka. Kurt recalled that visit years later:

In that first moment I received an indelible impression: the impresario was presenting the star he had discovered. This was true, of course, and if the impression was embarrassing, it had to do with Kafka’s personality; he was incapable of overcoming the awkwardness of the introduction with a casual gesture or a joke.

Oh, how he suffered. Taciturn, ill at ease, frail, vulnerable, intimidated like a schoolboy facing his examiners, he was sure he could never live up to the claims voiced so forcefully by his impresario. Why had he ever gotten himself into this spot; how could he have agreed to be presented to a potential buyer like a piece of merchandise! Did he really wish to have anyone print his worthless trifles—no, no, out of the question! I breathed a sigh of relief when the visit was over, and said goodbye to this man with the most beautiful eyes and the most touching expression, someone who seemed to exist outside the category of age. Kafka was not quite 30, but his appearance, as he went from sick to sicker, always left an impression of agelessness on me: one could describe him as a youth who had never taken a step into manhood.

One remark of Kafka’s that day helped account for Kurt’s impression of him as an innocent with wobbly confidence: “I will always be much more grateful to you for returning my manuscripts than for publishing them.”

The relationship with Ernst Rowohlt fell apart a few months later, after Kurt retained Franz Werfel, the Prague-born novelist, playwright, and poet, as a reader on lavish terms without clearing the arrangement with his business partner. By February 1913, using money from both his late mother’s prosperous ancestors and his Merck bride, Kurt had bought out Rowohlt, eventually christening the new firm Kurt Wolff Verlag and bringing Kafka and Brod with him. He raised more cash needed for the business by auctioning off parts of his book collection, and in case anyone missed the symbolism—may the old underwrite the new!—Kurt adopted a credo he articulated in a letter to the Viennese critic and editor Karl Kraus: “I for my part consider a publisher to be—how shall I put it?—a kind of seismographer, whose task is to keep an accurate record of earthquakes. I try to take note of what the times bring forth in the way of expression and, if it seems worthwhile in any way, place it before the public.”

*

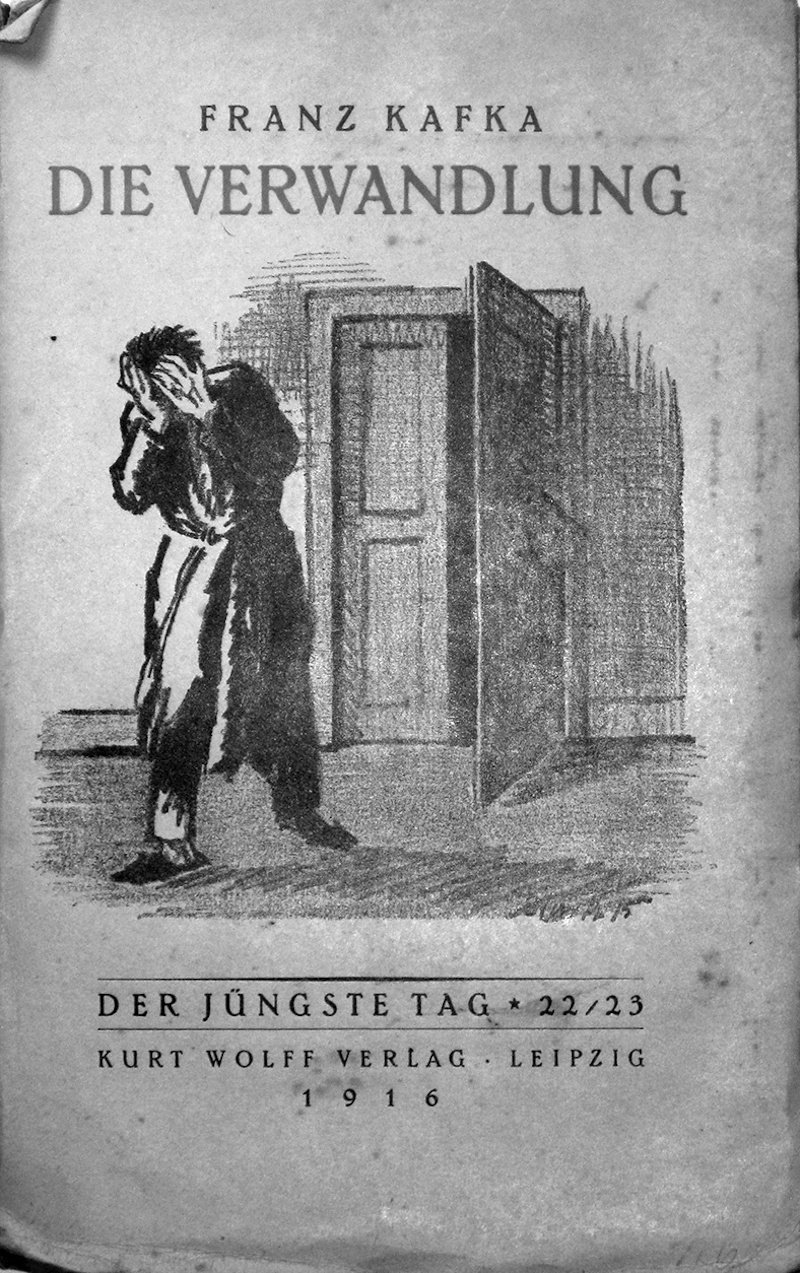

My grandfather had barely reached his mid-twenties, but his adult life was off to the headiest kind of start. In 1913 Kurt brought out the work of his two in-house readers, Werfel and the Expressionist poet and playwright Walter Hasenclever. He foreshadowed a long devotion to the visual arts by publishing the writings of the Austrian painter Oskar Kokoschka. And he launched the Expressionist literary magazine Der jüngste Tag (The Judgment Day), with which he pledged to showcase writing that, “while drawing strength from roots in the present, shows promise of lasting life.” Several years later Der jüngste Tag would feature a novella Kurt had referred to in a note to Kafka as “The Bug,” a work we know today as The Metamorphosis.

In 1913 the Bengali poet Rabindranath Tagore became the first non-European to win the Nobel Prize for Literature, and the Kurt Wolff Verlag eventually sold more than a million hardcover copies of a collection of his work, turning it into an under-the-Christmas-tree staple throughout Germany. In a January 1914 diary entry, Robert Musil, an Austrian writer in Kurt’s stable, described the man presiding over it all: “Tall. Slim. Clad in English gray. Elegant. Light-haired. Clean-shaven. Boyish face. Blue-gray eyes, which can grow hard.”

Kurt’s firm seemed to be making its way without having to compromise. “The house often functioned more as a patron of the arts than according to commercial calculations,” remembered Willy Haas, who joined Werfel and Hasenclever as a Kurt Wolff Verlag reader in 1914. Kurt had no interest in a kind of publishing where “you simply supply the products for which there is a demand,” he would write, the kind where you need only “know what activates the tear glands, the sex glands, or any other glands, what makes the sportsman’s heart beat faster, what makes the flesh crawl in horror, etc.”

My grandfather held fast to another view, a luxury he could afford, but that would later make his row tougher to hoe: “I only want to publish books I won’t be ashamed of on my deathbed. Books by dead authors in whom we believe. Books by living authors we don’t need to lie to. All my life, two elements have seemed to me to be the worst and basically inevitable burden of being a publisher: lying to authors and feigning knowledge that one doesn’t have… We might err, that is inevitable, but the premise for each and every book should always be unconditional conviction, the absolute belief in the authentic word and worth of what you champion.”

In 1914, after a lengthy courtship, Kurt finally landed Karl Kraus as an author. The Viennese Mencken was so prickly about whom he shared a publisher with that he and Kurt agreed on the only solution: to set up a subsidiary devoted solely to his work. Kurt also took over publication of the pacifist and anti-nationalist journal Die weissen Blätter (The White Pages), which would have to be printed in Switzerland after war broke out to dodge the censors. Even from his provincial haunts in Prague, Kafka noticed that Kurt was riding high, and said as much in a letter to his fiancée, Felice Bauer: “He is a very beautiful man, about 25, whom God has given a beautiful wife, several million marks, a pleasure in publishing, and little aptitude for the publishing business.”

Even after allowing that no publisher is commercially minded enough to satisfy the typical author, Kafka was on to something. “In the beginning was the word, not the number,” Kurt would say, many years later, in a riff on the Gospel of John. Der jüngste Tag nonetheless helped the Kurt Wolff Verlag carve out a niche as a purveyor of cutting-edge writing, and that was worth something. Though my grandfather had been raised to revere the classics, he knew enough to step back and let that rule of 20th-century marketing—if it’s new, it’s better—carry the day. For a while this worked. And it was an exhilarating time to be in the book business: during Kurt’s first year out on his own, no country produced more books than Germany, some 31,000 new titles in 1913 alone.

*

“The first days of a European in America might be likened to a re-birth,” Kafka wrote of the emigrant protagonist of his novel America. “One must nonetheless keep in mind that first impressions are always unreliable, and one shouldn’t let them prejudice the future judgments that will eventually shape one’s life here.”

This might have served as a cautionary note to Kurt, whose diary describes the whirl in the spring of 1941 after he, his second wife Helen, and their son Christian set foot on American soil after escaping Vichy France by way of Spain and Portugal with the help of Varian Fry and his Emergency Rescue Committee. On day one they checked into the Hotel Colonial on Columbus Avenue, where they were put up by Thea Dispeker, a refugee who had provided the US State Department with an affidavit of support. Within a month Kurt had filed “first papers” to start the clock, so they could all apply for US citizenship five years later.

But the doting attention quickly fell away. The kind of people who in Europe would have instantly recognized Kurt’s name now asked him how to spell it. Invited to a dinner party at a home on Long Island, he and Helen were struck that no American guest asked about what they, eyewitnesses to the rise of the Nazis and the fall of France, had lived through. They were physically safe. But new circumstances threatened their sense of identity, and identity is bound up in one’s native tongue, so essential to fully expressing one’s personality. Kurt knew he needed to improve his English, but with Christian he insisted on speaking German. “I do not,” he told his wife, “wish to communicate with him in a rudimentary fashion.”

As book publishing was the only way he knew how to make a living, Kurt hastily began to prospect for advice and capital. He met with publishers Alfred A. Knopf and W. Warder Norton, and reached out to his ex-wife’s cousin George W. Merck, the CEO of New Jersey-based Merck & Co., a prosperous pharmaceutical firm that had grown out of the American subsidiary established by the Darmstadt family in 1891 before being seized by the US government during World War I under the Trading with the Enemy Act.

“I for my part consider a publisher to be—how shall I put it?—a kind of seismographer, whose task is to keep an accurate record of earthquakes.”Figuring that the United States would soon join the war and, as in France, they would be rounded up as enemy aliens, Kurt and Helen had packed overalls and work boots, the better to survive an internment camp. But that fear gradually receded. For the first time they could remember, they didn’t know where the nearest police station was. “We’ve made some friends and acquaintances here, and we’re also getting to know many new people who are good-hearted and friendly,” Kurt wrote his daughter back in Germany, my aunt Maria, two weeks after their arrival. “But it will all be very, very hard, and we must very, very quickly find possibilities for work.”

Just turned 54, Kurt had been out of the publishing game for more than two decades. He and Helen spent much of the summer and fall holed up in the New York Public Library, trying to identify foreign literature that could interest American readers. They haunted concerts, lectures, and galleries and, means permitting, entertained—“inviting people for dinner if their guests were indigent or for a drink if they were not.” They spent that first Christmas with an old friend from Munich, the bibliophile Curt von Faber du Faur, who like the Wolffs had taken up gentleman farming outside Florence during the 1930s. Verlag besprochen—publishing firm discussed—Kurt’s diary reports of that visit to Cambridge, where their friend now lectured at Harvard. Soon Faber du Faur and his stepson, Kyrill Schabert, agreed to put up $7,500 if Kurt and Helen could raise a matching sum.

George Merck and two others ponied up, and by February, not a year after alighting from the Serpa Pinto, they were back in the book business. They named the firm Pantheon after Kurt’s old art-book house in Florence, Pantheon Casa Editrice, and in September moved into a grungy $75-a-month apartment on Washington Square South. The living room, dining room, and bedroom served as Pantheon’s office, mailroom, and reception area. “If I wish that these efforts might find some material reward in the not-so-distant future (out of the question for the time being), I do not say this because we want to get rich,” Kurt would write shortly after the firm’s founding. “All I wish for is improvement of our working conditions—an additional room and some professional assistance.”

It seemed unwise for Kurt and Helen, now indeed enemy aliens since the United States had joined the war against Nazi Germany, to formally head up the new business. So the original documents listed Schabert as president. The investment agreement further called for neither Wolff to be paid a salary until the house broke into the black. Eager for the New York literary world to take them and their enterprise seriously, Kurt and Helen sometimes strained to project an illusion of bourgeois arrival, as in a preposterous photograph where they posed with a dog that wasn’t theirs in someone else’s apartment. In early 1942 they caught a break when Kurt successfully crowbarred several thousand dollars out of his account at Barclays Bank in London. Otherwise, the émigré joke—“America, Land of Unpaid Opportunity”—obtained. As Thomas Mann would write Kurt in 1946, “You know yourself how these times and this country nip and gnaw.”

Kurt and Helen sometimes strained to project an illusion of bourgeois arrival.

Pantheon, Helen later recalled, “operated on a combination of tightrope and shoestring,” out of a “crazy office” marked by “a Babel of languages.” She and Kurt spoke French with one editor, the Russian-Jewish refugee Jacques Schiffrin, and German with another, the Bavarian anti-Nazi Protestant and Emergency Rescue Committee volunteer Wolfgang Sauerländer. Their order clerk was Albanian; their bookkeeper, Portuguese. “Grotesque as it may sound,” Helen wrote Maria in 1946, “I am the only person in the editorial and production department who knows some English (about father’s English the less said the better).”

Despite the firm’s unsteady footing, Kurt refused to abandon his standards. One day the staff took up the question of whether to use real or fake gold leaf to emboss lettering on the spine of a book. Kurt argued for real. A salesman made the case for fake, pointing out the savings on each copy. Kurt replied that fake would fade. The salesman countered that by then the buyer would be stuck with the book—a point that, as far as Kurt was concerned, settled the issue. Only real gold would do. “One has to learn this country like a new language,” Helen wrote her sister in Bavaria. “It doesn’t come naturally like a dream come true, like my oh so beloved France. There are no affinities to bridge the differences; everything has to be done by experience and intellect.”

Years later Kurt captured his ambivalence over being an entrepreneur in exile: “This wasn’t a gift from heaven, but a kick.” The nippings and gnawings of experience had also helped lead him to drift further from his onetime vow to embrace the new. In an unpublished document, Kurt sketched out a different mission for Pantheon—not to espouse the narrow interests of an Exilverlag, not to engage in politics or pamphleteering, not to flog the merely topical at the expense of the timely, but rather “to present to the American public works of lasting value, produced with the greatest care and stress on quality. Our editorial concept is to help spread knowledge and understanding of the essential questions of human life and culture.”

*

In 1955 Pantheon published Gift from the Sea by Anne Morrow Lindbergh, the wife of the celebrity aviator Charles Lindbergh. For Kurt and Helen, the book was a departure twice over. A slight collection of lessons learned during a life lived under public scrutiny, it seemed to hold out little lasting literary value. But the book signaled that Pantheon had gone native. An author from an iconic American family entrusted her thoroughly American story to an immigrant publisher. Knowing what advance orders foretold, Kurt could scarcely contain his gratitude when he wrote the author on the eve of publication.

I am thinking of you and your gift to us with an undivided heart, weighing it and what it has meant to me, Kurt Wolff, with… a sense of the miraculous. I had long since resigned myself to do my work in this country under the sign of [Pantheon author and French essayist and thinker Charles] Péguy—that is, in relative obscurity, one’s efforts disproportionate to their tangible results, braced and exhausted simultaneously by swimming against the stream. Whenever books were offered us by authors, agents, foreign publishers, they were inevitably the “difficult” ones, with the ones promising success going to the old-established, large American firms… It seemed a fateful, if irrevocable pattern. And that is why, in thinking of your gesture in giving us Gift from the Sea, I used the term “miraculous.” It was just that to me: the free, trusting, generous gift of an uncalculating heart.

Gift from the Sea sold 600,000 copies in hardcover and two million in paperback, certifying Pantheon’s naturalization in the world of American letters. Three years later came confirmation that this breakthrough had done nothing to diminish the firm’s reputation as a safe harbor for imported literature. The Russian writer Boris Pasternak granted world rights to Doctor Zhivago to an Italian publisher, Giangiacomo Feltrinelli, who in turn reached out to Pantheon through a British go-between with an offer of US rights. At the height of the Cold War, Kurt and Helen were entrusted to position the book as a literary title, not a political one, for in addition to selling the novel short, any false marketing step could imperil the author, a dissident in the Soviet Union.

Kurt would never meet his Russian laureate. After Doctor Zhivago became a global best seller, the Soviets kept Pasternak confined largely to his dacha outside Moscow and ultimately refused to allow him to accept the Nobel Prize. But my grandfather did his best to jerry-build a relationship on that favorite place of his, the page. Like Kurt, Pasternak had studied at the university in Marburg, with many of the same professors, including the Kant and Plato scholar Hermann Cohen.

“Our editorial concept is to help spread knowledge and understanding of the essential questions of human life and culture.”

Before the hammer of the Kremlin came down, Kurt wrote his author with the hope that they would soon have a chance to meet and reminisce about Marburg and Cohen—“perhaps,” Kurt suggested, “in Stockholm toward the end of 1958.” Meanwhile, he updated him on the reception of Doctor Zhivago in the United States, where a reviewer at a Chicago TV station had highlighted the novel’s lessons for Americans, who might now be inspired to stand up to oppressions built into their own system: “How quickly do we give in—to the boss, to the main chance, to the quick buck. How readily do we ‘play it safe, not half-safe’? What excuse do we find—in our personal life, in our business life, our life as Americans not to ‘rock the boat’—to relax, to conform, to play along.”

Fishing for endorsements for the book, Kurt had sent copies to William Faulkner and Ernest Hemingway. But he tamps down expectations that blurbs will be forthcoming. “Both are great writers, of course,” he told Pasternak. “But both are unreliable, seldom or never write letters, and both are alcoholics.”

__________________________________

Excerpted from Endpapers: A Family Story of Books, War, Escape, and Home. Used with the permission of the publisher, Grove Atlantic. Copyright © 2021 by Alexander Wolff.