How Dairy Lunchrooms Became Alternatives to the NYC Saloon ‘Free Lunch.’

Ben Katchor's Brief History of the Dairy Restaurant

The American Temperance Society was formed in 1826, but its origins go back to the 18th century. Through those years, it was a goal of the movement to provide an alternative to the saloons, then located on nearly every street corner, that attracted customers with an offer of free lunch with the purchase of beer or whiskey.

An 1895 editorial in The American Jewess explained that total abstinence was incompatible with Jewish culture as wine was used for rituals and at social gatherings and therefore the Jews could not join the temperance movement. By placing unjust restrictions upon behavior and commercial activities, the movement violated the civil rights guaranteed by the Constitution. The Prohibition Party and the Anti-Saloon League thus came into conflict with the urban Jew involved in business and moderate social drinking.

After the establishment of Prohibition in January 1920, special permits were issued for the sacramental consumption of wine. The number of spurious congregations requesting these permits led to the Internal Revenue Service calling for a repeal of these exemptions. Reform and Conservative congregations were willing to forgo the exemption and use unfermented grape juice. Orthodox congregations rejected this idea but offered no reason. The so-called raisin-wine controversy led to the widening rift between Jewish religious denominations.

While the temperance movement held Jews up as models of moderation in drinking, Jews worked as saloonkeepers, in the beer-and-spirits business, and, during Prohibition, were involved in bootlegging.

The physical comfort of a saloon was clear: “the warm, brilliantly lighted cheery barroom” in winter, and in summer, “the ice-cold lager beer and the breezes created by the electric fans.” The saloon was the social meeting place that crossed socioeconomic grounds for games, talk, and music.

Attempts at opening temperance hotels, restaurants, and cafes modeled after their alcohol-serving namesakes were never very successful. An ambitious Temperance Coffee House movement in England also came to naught. In the phenomenon of the dairy lunchroom, the temperance leaders saw their dream finally realized.

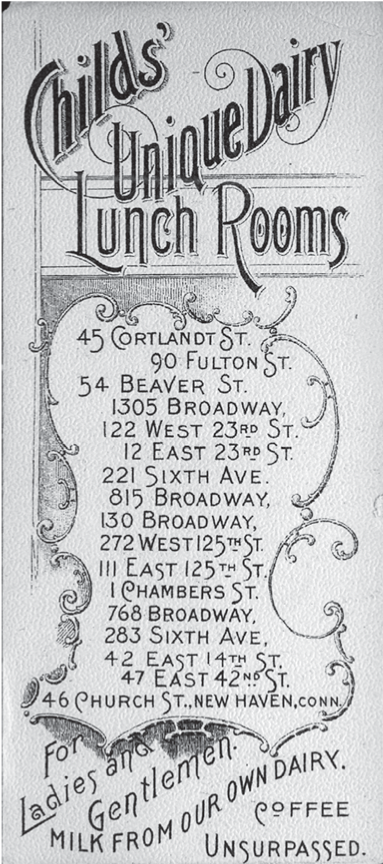

For an immigrant Jew, deciphering the English-language menus and eating in one of these American-style dairy lunchrooms would be a major step toward assimilation.“The crowded condition of the numerous ‘dairy’ restaurants of the well-known Dennett, Childs and Bailey type at many hours of the day demonstrates the fact that thousands of men are quite willing to pay more money for their lunch away from the saloon and its associations than the saloonkeeper asks, if only the places and provisions are to be found in convenient and attractable situations.” It was proposed “that the city should buy out a certain number of saloons in each ward” for the purpose of converting them into non-alcoholic lunch and meeting places. [The Independent, February 6, 1902]

The pure food movement of the 1870s was the culmination of a growing popular discontent with food and its handling, especially in big cities. The special attention directed to the problems of milk purity, in its supply and delivery, had people thinking about reliable sources from the nearby countryside and, by association, the spanking-white, easy-to-clean tiles of model dairy farms and milking rooms.

Clever restaurateurs must have seen the possibility of aligning themselves with this movement by offering an alternative to the spittle-flecked, sawdust-covered floors of the quick lunch counters common in that day. The heavy baronial-styled banquets and drapes could give way to a new scientifically based aesthetic of cleanliness and purity. What better way to attract customers than to appeal to their fear of illness due to unsanitary and unhealthful eating conditions.

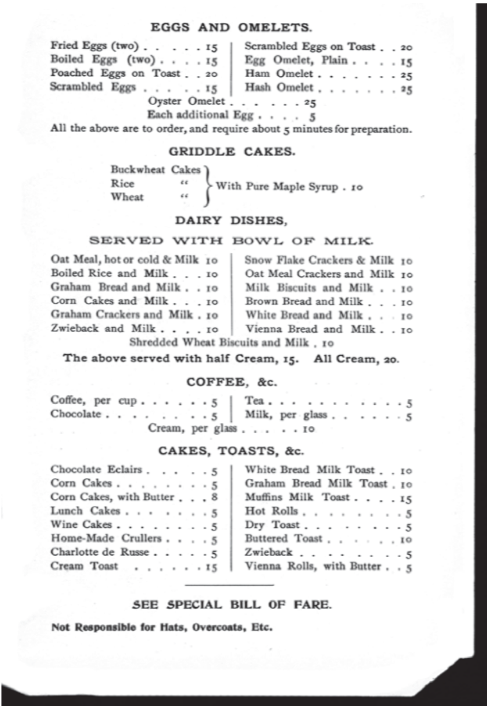

These dairy lunchrooms offered the Kellogg’s health-food products of the day along with a large selection of farinaceous foods, milk, and eggs. To appeal to the heavier eater they also included a substantial meat-and-fish menu. These popular establishments, like the Christian Meierei and Milchhallen of Europe, were dairy restaurants in name, decor, and spirit, but were not limited to a dairy-based menu.

In 1873, a branch of the Holly Tree Inn was opened in Brooklyn, New York, by the Woman’s Christian Temperance Association. It was a cheap eating house in which a meal and coffee could be purchased for 15 cents on a clean tablecloth in a neat, warm room. [New York Observer, January 2, 1873]

Two well-known dairy lunchrooms were located near the Jewish East Side: The Centennial Dairy Lunch & Dining Room at 106 Fourth Avenue, between 11th and 12th Streets, run by Hollingsworth & Grum [Important Events of the Century, 1876] and the Columbia Dairy Kitchen at 48 East 14th Street on Union Square. The Columbia Dairy Kitchen’s menu announced that it was open from 5 am to 1 am and featured “Pure milk and butter from our Shrub Oak Dairy Farm.” The service was summed up in a poem on the menu. “The Columbia Lunch so tempting, so neat, with jolly good company and comfortable seat. No five-minute lunch at some way station, No elbows to hunch, no quarter-ration.” It featured “Genuine Old-fashioned Griddle-cakes with pure Vermont Maple Syrup” for 10 cents. “These are the cakes men have long sought, and wondered where they could be bought.”

On its vast menu of roasted and broiled meats, oysters, and vegetables there’s a sizable list of dairy dishes: variations on a bowl of milk or cream with various cereals or breads. “The Columbia Orchestra will play popular selections every afternoon and evening. Ask the Leader to play your favorite selection while you dine. Table d’hôte dinner with wine served from 11:30 to 8 pm for 75¢.” The Columbia Dairy Kitchen was described as being “something of a curiosity for its size, its music and its methods.” [Ernest Ingersoll, A Week in New York (1891)]

For an immigrant Jew, deciphering the English-language menus and eating in one of these American-style dairy lunchrooms would be a major step toward assimilation. For the familiar dairy dishes of home, they’d have to patronize an Eastern European Jewish-style dairy restaurant, if one existed.

The Reason: A Journal of Prohibition from February 1886 carried ads for “DAIRY LUNCHES! PURE MILK CO.” at four locations in Chicago. “Our specialty: A glass of pure milk or butter milk, with one biscuit or bun, 5 Cents. Cheap, Cleanly Lunches. No alcohol surroundings.”

In 1881, the visiting secretary of the National Temperance League of Great Britain, Robert Rae, described the proliferation of dairy lunchrooms in many American cities. “One large establishment of the kind I saw at Washington, and there they were giving milk luncheons to the people who were flocking in to get them. A charge was made of five cents for a pint of milk. In New York, I found there were a great many of these Dairy Lunch Rooms opening up in various parts of the city. These Dairy Refreshment Rooms appear to be on the increase in our own country. We are acquainted with several in the City of London, and they seem to carry on an extensive business.”

“Dr. David Blaustein, superintendent of the Educational Alliance [1898–1907] declared that the Hebrews of the East Side had no liquor problem.” This fact was attributed to the moderation of drink in the cafes of the East Side. “In the district south of Houston St. and east of the Bowery there dwell 65,000 families, who support 200 cafes. The East Side cafe is an eating house by day and a drinking place by night.” The single men and women make up the daytime business. They work until 9 pm and then devote two hours to their intellectual development through lectures, concerts, and political meetings. “At the stroke of 11, however, the places begin to fill up for hard as his day’s work the East Sider must end it with an hour or two of social enjoyment. Tea prepared in the Russian fashion is the drink most in demand. If a man wants whiskey or beer the waiter goes out to the nearest saloon for it. There is no custom of treating. Each man pays for what he orders. Discussion of a wide range of subjects gives the necessary entertainment, and no fiery liquor is need to give it zest. There is little or no music, as it would interfere with the discussion. There are three kinds of cafes in this district—Russian, Rumanian and Galician. One finds intellectual life at its height about the tables of the Russian cafes. Tea is the drink, almost exclusively, and the discussion is most spirited.

“At the Rumanian cafes the light grape wine of the country is much in demand, but there is no drinking to excess. The discussions in the Rumanian places are not so lively, and card playing without gambling is indulged in. “Most of the patrons of the Galician cafes are older people. They write letters at the little tables, they bring their own books and read away the hours, sipping tea or coffee. The dietary laws are more strictly adhered to than at the cafes of the other two classes.

“The so-called ‘dairy’ restaurants and coffee houses that are scattered about the land and that are painted white are numbered by hundreds.”“The tone of the cafe depends upon the proprietor almost entirely. . . . His is a respected businessman and his opinions have weight. Where the musicians gather, one will find, usually, that the proprietor of the cafe is a musician. And so with the other professions, Socialists gather about a man who advocates socialism. Does anyone need a more extended explanation why the Jews have no drink problem?” [New York Daily Tribune, Sunday, April 14, 1904]

An 1891 report notes: “A few years ago a class of restaurant called dairies sprang up in the region below the Post Office [bottom of City Hall Park] which met with great success. They make milk and bread in a great variety of forms the standard nourishment, adding some simple desserts and pastries, and always berries and fruit in season. They are nearly all located between Broadway and the East River, below Newspaper Square.” They charged 5 cents for coffee. [Ernest Ingersoll, A Week in New York (1891)]

A reporter for The Sun in 1893 noted that “a surprising number of new restaurants of the cheaper sort are painted white. Probably their proprietors are following a fashion set by a New Yorker, whose bill of fare consisted largely of milk, who intended to imply as much by the cream-colored front of his place. The so-called ‘dairy’ restaurants and coffee houses that are scattered about the land and that are painted white are numbered by hundreds.”

__________________________________

From The Dairy Restaurant by Ben Katchor. Copyright (c) 2020 by Ben Katchor. Reprinted by permission of Schocken Books, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.