How Jean-Paul Sartre managed to spend his military service working on his novel.

On September 20th, 1939, Jean-Paul Sartre was conscripted into the French Army. Because of his exotropia, which he said caused him balance issues, and his partial blindness, he didn’t go to the front. Instead, they made him a meteorologist. It was, as he wrote in a letter to Simone de Beauvoir, “extremely peaceful work; indeed I cannot think of any branch of the services that has a quieter, more poetic job—apart, that is, from the pigeon breeders, always supposing that nowadays there are any of them left.”

“My work here consists of sending up balloons and then watching them through a pair of field glasses,” he explained. “This is called `making a meteorological observation.’ Afterwards I phone the battery artillery officers and tell them of the wind direction. What they do with this information is entirely their affair. The young ones make some intelligence reports based on it; the old school simply shove it in the wastepaper basket. In any event, since there is no shooting here at present, either course is equally effective. As for me, I am left with a huge amount of spare time on my hands, which I am using to complete my novel.”

Sartre was captured by German troops in 1940, and spent nine months as a prisoner of war, during which time he also wrote a great deal, and passed the rest of the hours by reading Heidegger’s Being and Time. (As you do.) It was his eyes again that led to his release—or his escape, depending on who tells it. “It wasn’t a very swashbuckling escape, but it was simple and it worked,” writes Sarah Bakewell in At the Existentialist Café.

He had been suffering a great deal from his eye problems, thanks to all the reading and writing—which were mostly done one-eyed. Sometimes both eyes were so sore that he tried to write with them closed, his handwriting wandering over the page. But his eyes gave him his escape route. Pleading the need for treatment, he procured a medical pass to visit an ophthalmologist outside the camp gates. Amazingly, he was then allowed to walk out, showing the pass, and he never went back.

Instead, he returned to Paris, and got back to work.

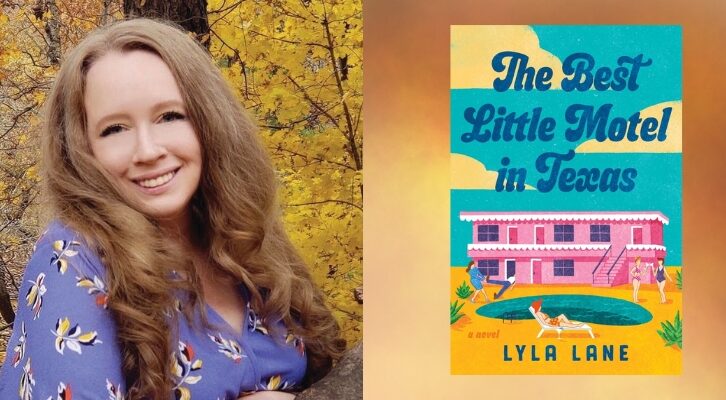

Emily Temple

Emily Temple is the managing editor at Lit Hub. Her first novel, The Lightness, was published by William Morrow/HarperCollins in June 2020. You can buy it here.