How It Took a Diverse Coalition to Truly Fight for Reproductive Freedom in America

Felicia Kornbluh on the Birth of the Reproductive Justice Movement

It was 1963, and Karen Stamm was unmarried, pregnant, eighteen years old, and eager for an abortion. A bright woman from a lower-middle-class family, she was finishing her education and in no way interested in having a child. Her home state of New York had treated abortion as a crime since the early nineteenth century. Starting in 1830, state law defined a carve-out or exception to the blanket illegality; it allowed a doctor to perform an abortion if he (and they were virtually all “he”) judged it necessary to save a woman’s life.

By the 1960s, this was known as “therapeutic” abortion and, for a small number of people who sought abortions, nearly all fairly wealthy white women, doctors interpreted the word “life” to mean something like quality of life. Doctors performed abortions for women who could argue successfully that an unwanted pregnancy would damage their mental health—and with whom the doctors were sympathetic. Stamm received approval on this kind of mental health basis.

Just before the procedure, at Montefiore Hospital in her natal borough of the Bronx, she recalled, “I was handed a consent form. It was a one-page consent form for the abortion. I read it, I signed it, I turned it over. The other side of it was a consent form for sterilization. And during the time I was there, I was approached by one of the staff doctors who told me that since I was so irresponsible, he was sure it”—pregnancy outside the bounds of marriage—“was going to happen again, and why didn’t I just turn the paper over and sign the other side and get it over with?”

The doctor persuaded her mother to join the chorus. In effect, he told Stamm that the same factors making her unable or unwilling to raise a child in her late teens, or the abortion itself, or the sexual activity that led to her pregnancy, or all three, made her permanently unfit for motherhood.

Despite the pressure, Stamm refused to sign the sterilization-consent page. “After that I made a commitment to myself, which was that if ever there arose a situation in which I could do something about this, I would do it.” That commitment led her to become a reproductive rights activist in the 1970s, first as member of a group called the Women’s National Abortion Action Coalition and then as a leader of the Committee to End Sterilization Abuse (CESA). She and other activists argued that, much as laws that criminalized abortion violated women’s rights by interfering with their ability to end a pregnancy, sterilization abuse violated their right to be parents.

What happened to Karen Stamm was the result of two big flaws in state abortion laws. First, while a small number of women could access legal abortions because their doctors believed they were psychologically unfit to carry unwanted pregnancies to term, the doctors might by the same logic push them toward sterilization: if one pregnancy was impossible on mental health grounds, doctors could use those same grounds to justify their sense that women seeking their help should never become mothers. Second, the whole idea of therapeutic abortion was that the procedure should be accessible only when medically appropriate. All power rested with the doctors, who may have been sympathetic to a young white woman with some economic means, like Karen Stamm.

But even when approving therapeutic abortions for women like Stamm, some doctors appear to have believed that pregnancy, abortion, and then sterilization were the wages of sin. Rather than have a sexually active unmarried woman return for a second abortion, or let her pass “promiscuous” genes to future generations, the doctor would perform a surgery on her and shape her future.

The two sides of reproduction, the right to it and the right to control or resist it, comingled in a different way for Loretta Ross than they did for Karen Stamm. Because of a malfunctioning birth control device, Ross lost the ability to get pregnant in 1973. It was the year of Roe v. Wade, supposedly a banner time for reproductive liberty. Ross was twenty-three years old and recently a student at Howard University, cream of the historically Black college and university (HBCU) system.

Ross had experienced the full brunt of America’s restrictive reproductive policies, becoming a mother at fifteen, then reneging on a promise to the staff at a Salvation Army home for unwed mothers that she would let them place her son for adoption, and becoming pregnant a second time because she needed parental consent for birth control. Ross aborted that pregnancy—legally, thanks to a federal court case that had liberalized the law in Washington, D.C.

Loretta Ross would eventually become a preeminent reproductive advocate and theorist. But in the early 1970s, as a student whose third pregnancy occurred while taking (and occasionally forgetting to take) the Pill, Ross asked at the university health center for an easier-to-manage form of birth control. The student medical clinic at Howard offered, free of charge, a long-acting, difficult-to-remove intrauterine device (IUD) called the Dalkon Shield. “And of course it was a defective IUD that ended up causing acute pelvic inflammatory disease, [which traveled up] the fallopian tubes” and went undiagnosed for months while she was under the care of a doctor who chaired the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology of a major teaching hospital.

Ross wound up with a full hysterectomy and considers herself a victim of sterilization abuse. She remembered with a lilt of irony: “To be told at twenty-three that one shall not have any more children, it has a way of getting your attention.” As she sees it, the Dalkon Shield was the kind of long-acting birth control method that was “very attractive to people who are making decisions about the fertility of vulnerable women.” Ross “didn’t get any information on contraindications” or potential risks, she remembers.

After her experience, Ross became an activist. First, she sued the company that made the malfunctioning IUD, A.H. Robins. She realized, too, that she was hardly the only Black woman she knew who had been sterilized through one means or another. Much later, after years of work linking people who were passionate about abortion rights with those who cared about sterilization abuse, Ross co-convened a meeting of women of color in the movement in 1994. The group coined a new term to describe their agenda, a broader understanding of reproductive rights: “Reproductive Justice.”

*

In the era just before and after Roe v. Wade, the movement for the decriminalization of abortion and then for abortion rights was relatively strong and mainstream. In this period, the movement’s leaders missed possible connections with what was then a rising movement against sterilization abuse – a movement that would have spoken to experiences like Loretta Ross’ and would have stood not only for the right to end a pregnancy when one chose to but also for the right to bear and raise children when and how one chose to do that. The missed connections occurred for two reasons.

One was a genuine difference of philosophy: a belief on the part of sterilization-abuse opponents in the need for strict regulations to prevent abuse, and an equally strong belief on the part of some advocates of abortion rights that such regulations themselves threatened people’s reproductive autonomy. Second was a sense on the part of many proponents of abortion rights that they could not afford the risk involved in expanding their mandate to include new issues when they were in a hard fight to preserve the legality and accessibility of abortion.

It seems in hindsight that the movement for abortion rights might have been stronger if it had embraced those risks instead of shying away from them. Of course, opposition to legal abortion has been forceful and persistent. However, politics that have started and ended with defending abortion have proved vulnerable to attack in ways that a broader agenda that included opposition to sterilization abuse and a defense of all people’s right to parent might not have been. An abortion-centered approach created opportunities for conservatives to pursue their agenda of remaking the Republican Party, vanquishing its liberal wing, and marrying economic policies that favor the wealthy with sexual and reproductive policies that appeal to a supposedly moral majority.

In addition to what appears in retrospect to have been an inaccurate assessment of risk, leaders in the most mainstream reproductive rights organizations were weakened by limitations in perspective. Most white people in the movement to decriminalize abortion did not examine their white privilege or how privilege and the lack of it structured women’s experiences of sex and reproduction. And so racial bias affected their “vision as does a faulty lens,” in the words of the Puerto Rican public health leader and CESA co-founder Dr. Helen Rodríguez-Trías.

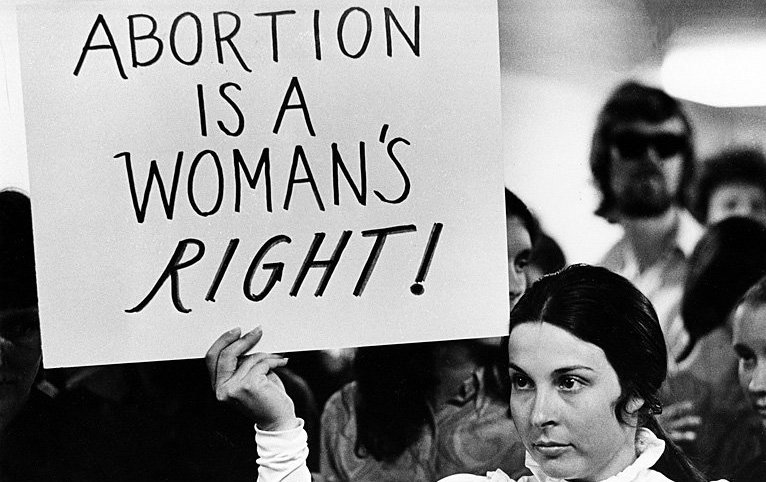

Still, the fight to decriminalize abortion was by itself a vital and historic one. As feminist legal thinkers started to argue in the late 1960s and early 1970s, the criminalization of abortion was part and parcel of a legal regime that demeaned and diminished all women. Laws that forbade doctors from performing abortions or women from obtaining them never kept abortions from occurring. However, they made it difficult, expensive, perilous, and sometimes deadly to obtain what had the potential to be a fairly safe medical procedure.

These laws, products of all-male or mostly all-male legislatures, in theory affected everyone equally but in fact harmed Black women, Latinas, young and unmarried women, and working-class or poor women the most. For this reason, many of the important, although rarely remembered, leaders of the movement to decriminalize abortion in New York and nationally were Black people who were committed to Black freedom and equality as well as to women’s rights. Harlem’s assemblyman Percy Sutton, for example, introduced the first bill in the state’s modern history to liberalize the abortion laws.

Labor leader and public administrator Dorothy “Dollie” Lowther Robinson proposed an amendment to the state’s constitution that would have codified equality on the basis of sex and made access to abortion a component of that equality. Activist attorney Florynce “Flo” Kennedy helped put the issue of abortion decriminalization before the membership of the National Organization for Women and later served as one of four co-counsels in the first federal case that made women, not doctors, the subjects of abortion litigation.

The most significant contribution of the movement to decriminalize abortion was its forceful recognition of women’s personhood. By insisting on women’s rights to obtain safe, legal, and affordable abortion care, the decriminalization movement said in effect that women’s lives mattered, not because of their capacity to bear children or to be partners to men but in themselves.

My mother, the late Beatrice Kornbluh Braun, made a particular contribution as a lawyer and member of the National Organization for Women (NOW) in New York. She outlined legislation that would have removed abortion fully from the state legal code. Weeks after she shared her draft, it was a bill, the first proposal for full decriminalization of abortion introduced into any state legislature in the country. And although it would be modified before passing, it was a landmark because it encapsulated what had become by the late 1960s the position of most feminists—that rather than reform the old laws as some lawyers and doctors wanted to do, government must repeal all controls on abortion and allow women to decide for themselves when it was right to terminate a pregnancy. My mother’s draft expressed in legislative terms the insistence of Florynce Kennedy and thousands of others that abortion shouldn’t be regulated any more than appendectomy should.

The statute my mother helped pass eliminated criminal sanctions for doctors and patients before the twenty-fourth week of a pregnancy, and imposed no residency requirement on people who sought abortions. After its implementation in July 1970, pregnant people from across the country and the globe found their way to doctors in New York, testifying to their need and to the lingering inequality between those who could and those who could not get there. The cost of abortion declined. Maternal mortality dropped dramatically, especially for Latinas and Black women, who had accounted for virtually all the deaths from illegal abortion in the years just before the New York law changed. Decriminalization in New York was not everything, but it was a very big thing, particularly before the Supreme Court ruled on the constitutionality of Texas’s abortion law in Roe v. Wade. Stanley Katz, a former law professor and American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) lawyer, has said that in the movement for decriminalization of abortion, “we all looked to New York…We never expected the Supreme Court to bail us out.”

*

Part of the reason that Dr. Helen Rodríguez-Trías and her allies in the Committee to End Sterilization Abuse arrived at the sterilization issue sooner and with greater urgency than other feminists was that she had spent much of her life in Puerto Rico. Not only the locus of a morally troubling large-scale study of the birth control pill, Puerto Rico was also the first place in the world with mass population control via sterilization.

Sterilization in Puerto Rico resulted from partnerships between government and private funders, and a meeting between families’ desires for birth control and the limited options they were offered. It also resulted from an artificial separation between sterilization and abortion, with one becoming legal and popular and the other criminalized. The birth control movement in Puerto Rico predated the rise in sterilizations. In the 1920s, legalizing birth control was a Socialist Party cause, and Puerto Rican nurses and social workers opened the island’s first birth control clinic in the 1930s. In 1935, the New Deal government of Franklin D. Roosevelt assumed management of the birth control program on the island.

From the perspective of policy makers in Washington, D.C., this birth control program became problematic when opposition to it arose from Puerto Rican nationalists who treated it as an example of imperialist policy. Fearful that Catholics who heard about their dissent would desert the Democratic Party, the administration of Franklin D. Roosevelt withdrew its support from the program. A scion of the Procter & Gamble Company fortune and population control enthusiast named Clarence Gamble became the program’s main backer. He financed private clinics and a Maternal and Child Association (Asociacion pro Salud Maternal e Infantil) whose main purpose was to provide contraceptives and gather data about their effectiveness—as distinct from supporting the overall health and wellbeing of Puerto Rican citizens.

He advocated the decriminalization of birth control, which occurred in 1937, the same year that the Puerto Rican government legalized sterilization and created a eugenic sterilization board to make decisions about mandating involuntary sterilizations. Thousands of Puerto Rican women eagerly became patients of these clinics. In the Puerto Rican legislation of the late 1930s, sterilization was allowed for “health reasons,” which came eventually to cover all reasons for all people of childbearing age who sought sterilization. Unfortunately, many of the non-sterilization birth control methods Puerto Ricans were offered were experimental ones, provided by rich inventors like Gamble and representatives of major pharmaceutical companies who seized the opportunity Puerto Rico presented to test products that could make them millions in the U.S. market. Some of the things they tried were rankly ineffective. Others, like the early generations of the IUD and of the highly effective birth control pill, could be downright dangerous.

The most significant contribution of the movement to decriminalize abortion was its forceful recognition of women’s personhood.Sterilizations, the ones that were ostensibly voluntary, became an ever more popular contraceptive option. This helped give Puerto Rico the lowest level of population growth in the Caribbean by 1955 and the highest national sterilization rate in the world, at over 35 percent, by the end of the 1960s. Two-thirds of those sterilized were in their twenties.

In the overwhelming majority of cases, neither the U.S. nor Puerto Rican governments forced women into sterilization. At the same time, as sociologist Iris Lopez and others underline, the language of “reproductive choice” was hardly accurate in describing Puerto Rican women’s very high rates of sterilization. Puerto Ricans asked for or consented to sterilization as they sorted out their lives—lives shaped by, among many other factors, imperialism, racism, economic opportunity, economic inequality, sexism, and other factors.

On the U.S. mainland, just as there was a long history of Black, brown, disabled, and poor people being compelled or persuaded into sterilization—the involuntary sterilization of Black women was common enough to be known popularly as the “Mississippi appendectomy”—people who were native-born, white, able-bodied and -minded, and relatively well-off were unable to become sterilized when they wanted to. By the 1950s medical professionals typically used a rule of 120: a woman’s age multiplied by the number of children she had borne had to total 120 or more before they would accede to her sterilization request.

This meant that a woman of thirty would not be sterilized unless she had four or more children. The American Medical Association and American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists endorsed this 120 rule, as did many hospitals. Such policies had real power although they were not written into legislation. They changed only after they were challenged openly, and even then did not change completely.

The Committee to End Sterilization Abuse emerged against this background. CESA members focused on controlling the internationally imperialist and domestically racist and class-based dimensions of population policy. The CESA version of reproductive rights was upside down to that of the Supreme Court majority in Roe v. Wade. The Puerto Rican, Black, and leftist white feminists in the group argued that racist doctors were pressuring their clients, shielding vital information, and removing women’s ability to parent no matter their desires. By contrast, Justice Harry Blackmun wrote the Roe opinion as though the interests of doctors and their patients were virtually identical.

*

The story of how a diverse group, mostly of women activists, revolutionized abortion law shows how effective a political coalition can be when it throws everything it has at its chosen problem—from disruptive civil disobedience, to demonstrations of commitment by people of faith, to tireless lobbying that holds fence-sitters “on the pan” until they feel the heat of their constituents’ dissatisfaction, as Assemblywoman Constance Cook, cosponsor of the New York law, described her method of rounding up votes for a bill.

It is also relevant at a moment when democracy is increasingly imperiled. New Yorkers like my mother were hardly alone in fighting for changes in their state abortion law. From 1965, when Assemblyman Sutton introduced his abortion law reform bill, until 1970, when a version of the bill my mother outlined passed into law, the democratic system seemed to work. Across the country, public opinion gradually turned against the old, highly restrictive laws. One state after another passed reform legislation. New York’s was the most liberal, and Washington State’s, approved by referendum in that November’s elections, the last.

The story of the fight against sterilization abuse teaches a similar lesson. After the Roe decision, Dr. Helen Rodríguez-Trías, Karen Stamm, and other members of the Committee to End Sterilization Abuse soured on a politics that treated access to abortion as the be-all and end-all of women’s reproductive needs. In 1976, they organized successfully for a New York City law (passed by a vote of 38–0, with three abstentions) to eliminate sterilization abuse. In 1978, CESA and the newer Committee for Abortion Rights and Against Sterilization Abuse organized nationally to get the federal Department of Health, Education, and Welfare to mirror the New York City law in regulations that applied to all health-care institutions that received funding from the department.

Like the story of how activists changed the law of abortion, the chronicle of the fight against sterilization abuse is one of legal change that occurred not from the courts down but from the grassroots up. They stumped for endorsements from feminists, civil libertarians, Black and Puerto Rican movement groups, and progressive doctors, but not from doctors in the mainstream of their profession or experts in population science.

The wider reproductive rights movement that opponents of sterilization abuse represented created new ideas. Rodríguez-Trías, Stamm, and other leaders took on the problem of sterilization abuse because it was a crisis on both the island of Puerto Rico and the U.S. mainland. But they did not only battle an evil. They also outlined an ambitious and forward-looking political program: What, they started to ask, would it mean for people to have the right to parent, as well as the right to choose not to parent via contraception and abortion? Their allies encapsulated this program in the term “Reproductive Freedom,” meaning women’s “possibility of controlling for themselves, in a real and practical way—that is, free from economic, social, or legal coercion—whether, and under what conditions, they will have children.”

__________________________________

Kornbluh will be in conversation with Cynthia Nixon as part of the Books That Changed My Life Festival at the Marlene Myerson JCC on Jan 17.

*

Adapted excerpt from A Woman’s Life Is a Human Life: My Mother, Our Neighbor, and the Journey from Reproductive Rights to Reproductive Justice by Felicia Kornbluh. Copyright © 2023. Available from Grove Atlantic.