In the moments before entering every supercell thunderstorm, there’s a moment of pause that washes over me. It usually comes as daylight vanishes, a few seconds after I turn on my headlights; just before the first raindrops, and just after the wind has gone still. I silence the radio, tighten my seatbelt, and lower my armrest. Here we go again, I think. There’s no turning back now.

Then it hits, in this case like a car wash. The strongest storms often have the sharpest precipitation gradients. There’s no gradual arrival of the heavy rain. You’re either in or out. And I was in it.

My windshield wipers flailing wildly to and fro, I peaked at the GPS map and radar display guiding me. “Hmmmmmmm,” I muttered. “This is going to be tight.”

The storm wasn’t moving fast, but it was moving east; I was approaching from the north at a right angle. That meant I’d be hard-pressed to get into the storm’s vault, or precipitation-free notch east of the circulation, in time. I’d instead end up plowing through the hail core, escaping south of the rotation’s path right before it passed over my location.

The strongest storms often have the sharpest precipitation gradients. There’s no gradual arrival of the heavy rain. You’re either in or out.I considered my options. I could bail on the storm, wait for it to pass me, or thread the needle. Which meant slicing into the heart of the storm’s rotating hook echo.

But threading the needle can be iffy. If there is a tornado on the ground, you might not see it until the last minute, when you emerge from the rain and hail and it’s virtually on top of you. It’s easy to fall into the trap of trusting radar data, but it’s often outdated, and can lead to complacency. Plus, rural cellular networks make it unreliable, with spotty service at best. I didn’t see any indicators of a tornado on the ground though based on radar aberrations, and decided to continue south.

The familiar high-pitched metallic pinging of hailstones ricocheting off the hood commenced, a sound I find oddly soothing; once again, I was right at home in my natural habitat. Sheets of rain still poured down, the hail becoming larger. It was no longer striking my windshield directly, now large enough that it couldn’t fit through gaps in the fence-wire welded to the hail cage above. I knew that meant the hail had to be about the size of half dollars.

It was growing louder, a few golf ball–sized pieces mixing in. I reached for my safety glasses, a precaution I always take in case of shattering glass. My front and back windshields were protected, but the side windows were not. I’d never lost any of them, but there’s a first time for everything.

Cresting a hill, little was visible against the sky’s greyscale background, the hail shaft greedily sapping color from its surroundings. After minute or two being bombarded by hail, I began to discern the silhouette of a wall cloud about five miles to my southwest, casually lurking halfway above the ground. I was closing in. But just then, an impact struck the roof of my truck. It sounded—and felt—like a brick had been dropped on me.

I watched an icy projectile explode on the roadway up ahead, a white blur disappearing in an explosion of fragmented shards. A mischievous smile crept across my face. I knew what was coming. Seconds later, I was in a batting cage. Baseball-to softball-sized chunks of ice hurtled out of the sky at speeds topping 100 mph. Some shattered on the pavement, while others bounced upon impact and splashed up mud in adjacent fields.

I drove through a thicket of trees, the pavement slick and green from a fresh coating of shredded leaves. It smelled like Pine-Sol. Every twenty seconds or so, the truck was rocked by an enormous thud, hailstones striking either the rooftop or landing in the pickup bed. Some collided with the hail cage, harmlessly deflected from the flexing web of fencing and metal. A few even skimmed along the driver’s side exterior, narrowly missing my window.

I was alone; no cars passed by, and the breeze was still. Yet the wall cloud churned closer, producing occasional funnel clouds.Eyeing the wall cloud and knowing the hail had another ten minutes to go, I decided not to chance it. I swiftly pulled off the road and backed into the driveway of an isolated farm house, praying whomever lived there would be friendly. I thought back to the gun-toting Oklahoma man who threatened to shoot me for turning around at the foot of his driveway just days earlier.

No lights were on in the single-story house, either because no one was home or because the power was out. A mound of dirt sat in the front yard, with a few dilapidated strips of chicken wire circled into short makeshift pens or trellises. A rusted green riding mower sat surrounded by clumps of grass adjacent to a bird feeder. A stone birdbath, perfectly positioned between two trees yet tilted slightly off-kiter, was overflowing with rainwater. The home was covered in white vinyl siding, a tin roof hanging over the front porch and wrapping around to form a carport occupied by two white pickup trucks. A pair of Big Wheel tricycles were strewn haphazardly about the front yard. Each thunderous impact on the home’s roof sounded like someone swinging a hammer against sheet metal.

“Is it gon’ make a tornado?” a voice shouted. Startled, I whipped my head right, a man in a plaid shirt pressed up against my open passenger-side window. Apparently, somebody was home after all. “It’s trying,” I said, pointing the wall cloud.

“Yeah, it’s getting close,” the man said anxiously, shaking his head. I tried to hand him a hard hat, incredulous that he would be nonchalantly standing outside as lethal meteorites of ice pounded down. He seemed unfazed.

“Yeah, I’m all right,” he said, seemingly distracted.

In the most severe hailstorms, water in the cloud is divvied up into much larger hailstones, meaning fewer of them can form. That leaves a bit of space between where they fall. The man, however lucky, was playing a deadly game of dodge ball in a minefield.

I asked him if he minded me parking in his driveway.

“I don’t care,” he said, his attention turning to the sky once again. The wall cloud was only two or three miles to the west. “Yeah, that doesn’t look good.” He took off, disappearing into the house. I turned back to the wall cloud.

A moment later, the front door clacked open. The man and his wife, each carrying a small child, dashed toward the dirt pile in the front yard. He reached behind it and grabbed something—a door. They were heading into their storm cellar. I was alone; no cars passed by, and the breeze was still. Yet the wall cloud churned closer, producing occasional funnel clouds.

Amidst my continued pummeling, I had the perfect view, but decided to bail south out of the hail-laden bear’s cage before the wall cloud tracked overhead. A mile south, I pulled to the berm of the roadway, now watching the mesocyclone crawl just above the ground and revolve like a malevolent birthday cake. Grass and grain bowed down in waves, showing reverence to the atmosphere above. It rippled in the river of strong inflow winds feeding into the storm from the south.

Despite a few funnels shedding off the main updraft, though, it appeared to me the storm had lost its gumption. Looking west, the sky beneath the distant cloud base was orange. It was around 8:15 p.m. A textured lowering hung beneath one of the clouds, but radar didn’t show much there. I didn’t think much of it. To the east, the tops of faraway thunderstorms had become heaps of cotton candy, their rosy-pink paint strokes emblazoned against the graying horizon.

I rested against my truck and sighed. It was a good day, I told myself. A mothership, giant hail, and some funnels. Not bad for 2020. I casually strolled around the truck, inspecting for new dents. There were plenty to be found. “Oh, ho, ho!” I exclaimed, my eyes lighting up. “That’s a bigg’un!”

I leaned down to get a closer look at a large divot impressed in the hood. There were a few more dents of similar magnitude on the driver’s side door and rooftop. My father, a car aficionado, would have cried if he saw them. But I was ecstatic.

“Battle wounds,” I declared, no one around to hear me but the breeze.

I smiled smugly, satisfied with the scars of a good day.

I often hope that life winds up being like my truck: beaten, driven to the limit, and with a hell of a story to tell. Some people never take their vehicles out of the garage, passing up the chance to go for a ride for fear of getting them dented or dirty. Sure, those cars will always look pristine, but their odometers are empty. My road may not be paved, but every scratch, scar, and bump is a memory, an experience, part of the journey. I want a life with a lot of dents.

Little did I know the day had more in store. A quick check of radar showed that storms were beginning to clump together and grow upscale, becoming a cluster with a diminished tornado potential. I decided to pack it up and head back to a hotel an hour and a half east in Gainesville, Texas. I drove north, then east, the dusky sky illuminated by constant lightning strikes. It was as though monochromatic police strobes were bearing down on me.

Eventually, the storms reshaped into a line oriented southwest to northeast, with several embedded more intense cells. Wind and hail were still concerns, but the tornado threat was quickly decreasing with the setting sun. From in between flashes, a cloud to my north seemed to be dipping lower than the rest. Instinctively, I pulled over, watching out the windshield. A few specks of rain rested on the glass, while tree frogs and crickets sang their chorus outdoors.

I had to face the facts: three areas of spin, all of which could be tornadic, would pass within a few miles of me; one to the north, one directly overhead, and one to my south.Exhausted but relentless, I opened the RadarScope app on my phone, the display resembling a bucket of spilled paint. “Humph,” I grunted. Maybe a little something-something? The rotation seemed fleeting, though, and I wasn’t convinced it would hold together within a line of storms. I decided to instead sit back and seize the opportunity to post some photos and videos from the day to Twitter, hoping to capitalize on the ongoing storm buzz and pick up a few new followers.

Suddenly, however, my phone yelped, hissing its three-tone alert. I leapt, spilling my water and knocking my Nikon camera onto the floor. I suspected a flash flood warning had been issued. I reached for my radio.

“At 8:27 p.m. Central Daylight Time, a severe thunderstorm capable of producing a tornado was located near Bellevue, or seven miles west of Bowie,” the radio warned. I sat upright, surprised. It was a tornado warning. And I had just been in Bellevue minutes earlier. Flipping back to radar, I could see why: rotation had increased dramatically in a kink in the line, and the circulation was just to my north by a mile or two. I knew I hadn’t been imagining when I saw that suspicious cloud.

I figured I was in a fine position where I was to let the rotation pass me by. The road network wasn’t great, the only roadway heading from southwest to northeast into Bowie; that was parallel to how the storms were moving, too, so as long as I stayed put, the problematic cell would miss me just to my north.

But the radio hissed again. I squinted at my phone, skeptical that the signatures I was seeing were accurate. If this is legitimate, there are two more rotations, I thought. It was about to get ugly.

Sometimes, weather radars get tricked by high velocities within a cloud, and range folding can plot spurious signatures. That’s what’s going on, I thought. But a new scan came in, and the winds hadn’t changed. All three rotations were getting stronger.

I had to face the facts: three areas of spin, all of which could be tornadic, would pass within a few miles of me; one to the north, one directly overhead, and one to my south.

I was faced with a choice, but none of the options were optimal. I was on an east-west road, with no north-south options; the nearest intersection was in Bowie, seven miles to my east. If I tried to escape north or south, it would be fifteen or twenty minutes before I was in the clear. I didn’t have that kind of time. I could try to position in between circulations, but that would be risky, too. All three mesocyclones were like atmospheric sink drains, with potentially destructive straight-line winds orbiting around the vortex. Sitting between a pair of rotational couplets meant facing off against 70–80 mph gusts on a deserted roadway bordered by flimsy power lines. Plus, additional areas of spin could form, and I’d have no shelter.

Without a viable choice, I decided my best option would be to ride out the middle circulation in Bowie. I’d be in a town with access to shelter, and roadways in all four cardinal directions in case an escape route opened up, and it was comforting to know other people would be nearby. I raced east to Bowie, greeted by sirens as soon as I entered town.

The roadways were desolate, traffic lights rolling through their sequence against the backdrop of a rain-soaked roadway. The winds were still; a light rain was falling. Maybe this won’t be so bad, I thought.

My road may not be paved, but every scratch, scar, and bump is a memory, an experience, part of the journey. I want a life with a lot of dents.I had ten minutes until the worst was set to arrive. But the radar wasn’t encouraging—it wasn’t looking good. I knew that less than a third of rotational couplets produce tornadoes, though, and there was a majority chance the spin would pass with little fanfare. I was wrong.

Winds along the thunderstorm gust front showed up within moments; so did rain. The rain progressively got heavier, winds now lightly stirring. Radar said the rotation was just overhead. No tornado. I shrugged off the storm, and used the GPS to route myself to Gainesville, Texas, to spend the night. Well that was anticlimactic, I thought.

As I drove north through the heart of town, I knew something was wrong. The rain was increasing in intensity, and the winds beginning to change direction. I realized that the radar had been scanning high aloft in the storm, and wasn’t representing conditions at the surface; the vortex near the ground still hadn’t arrived.

Flash! A bright blue burst of light lit up the landscape to my north. Then another. Power flashes, I thought—a sign of electrical infrastructure being damaged or destroyed by high winds.

Around that same time, a twig bounced off my window. It hadn’t come from a nearby tree, though; it fell from the sky. And something had to have sucked it up there.

Suddenly, the town went dark. Main Street was pitch black, the sound of the sirens vanishing as the wind whispered louder. Rain fervently splattered on my windshield, as if trying to seek refuge inside. Then the fog hit, a milky shroud swallowing my vehicle. Visibility dropped to hardly fifteen feet, gusts of wind shaking the truck. The air was becoming saturated, but the temperature wasn’t changing. There had to be a powerful funnel of low pressure nearby.

I unconsciously slowed to ten miles per hour, then five, then four, then two. With the wind blowing straight at me and leaves and debris rocketing past the windows, I thought I was still driving rapidly; in reality, I was stationary. That’s when the edge of the tornado arrived.

The truck leapt side to side, the wind working as if to pry off the hail cage or the hood. Knowing the heart of the tornado was seconds away, I frantically checked my surroundings. Through the maelstrom I could faintly make out a brick wall thirty feet to my right. I revved the engine, clipped the curb, and pulled up in front of the wall. It was one of several; the structure was apparently a self-service car wash.

I unhooked my camera from the dash mount, making sure it was still recording. Shelter was close, only ten feet in front of me, but that was still too far away. Wind gusts at 80–90 mph had pinned my door shut, as if an invisible linebacker was working against me.

I kicked my legs against the center console, stretched out my body, and shunted the door ajar with my shoulder. It was my shot to escape. An instantaneous lull afforded me a second or two to slip out, suddenly bracing against the tornado’s fierce winds. A spattering of raindrops struck me, stinging as if they were solid.

The truck’s door slammed behind me, but I didn’t care. I was already inside the wash wells, crouching in the lee of a steel-and plumbing-reinforced cinderblock divider. Assuming it wouldn’t topple, my concern shifted to the corrugated roof. I watched as tree limbs, building materials, and a litter of other debris hurled by, projectile silhouettes against the headlights of my parked pickup truck. A piece of sheet metal narrowly missed the vehicle, careening south in winds gusting near 100 mph. The wind sounded like an enormous compressor.

Virtually every yard seemed to have trees snapped or downed, some resting on homes or having fallen on cars, while sheds and carports lay mangled.“Alrighty guys, we’re getting winds of one hundred miles per hour!” I shouted into my camcorder, pointing it outside the building. “We have debris flying by right now. We are likely in a tornado.” The final words faded into the jet-like roar of the wind. But it was over as fast as it came. Forty seconds later, the winds relaxed, the ferocious rush of air receding. It was louder in my left ear than right; I assumed the tornado was moving east-southeast. “So much for sounding like a freight train,” I muttered, rolling my eyes and smirking.

I sauntered back over to the truck, pulling the hood of my rain jacket over my eyes. The air smelled like a giant lawnmower had just churned up all the dirt and trees. I plopped down in the driver’s seat, turning on the air conditioner to wax away the fog on the window. I shivered, soaked in rain and sweat, and clicked on the seat heater. I yawned, suddenly aware of how tired I was.

Fighting the urge to shut my eyes, I tapped my phone, once again preparing to route myself to Gainesville, Texas. I frowned. The network was down, probably due to severed power or toppled cell towers. I knew I had to head north. I shifted into reverse, checking my backup camera for debris. Specks of shrapnel glinted in the headlights. I made it fifty feet to the main road before I was forced to stop. A pair of tree limbs, each a foot thick, were blocking the roadway. I was just here, I thought. Traffic signs, branches, and occasional building supplies were strewn about, slowing my progress to a crawl.

Toppled wires blocked multiple lanes. I relied on my headlights to help me avoid ongoing flash flooding; pools of water a foot and a half deep inundated low-lying parts of the roadway. I decided to tour a neighborhood that looked to have been in the apparent tornado’s path. Widespread EF0 to EF1 damage, commensurate with winds of 80–100 mph, was evident. Virtually every yard seemed to have trees snapped or downed, some resting on homes or having fallen on cars, while sheds and carports lay mangled. The next morning, the National Weather Service in Fort Worth confirmed it was an EF1 twister that had stampeded through town.

Meanwhile, it was now past midnight. I had been up for twenty hours straight, driven nearly six hundred miles, been to three states, and been concentrating nonstop since around lunchtime. It was time to get to the hotel.

White-knuckling it the remaining ninety minutes to Gainesville wasn’t fun. In heading east, I caught up to the storms, reentering their heavy rain from behind. I drove on the crown of the road, avoiding dozens of power lines that had been knocked over like dominos in bursts of straight-line winds. When I finally arrived to my hotel, the wind were back at 60 mph. I parked in the parking lot, slung my backpack over my shoulder, and nonchalantly shuffled into the hotel, refusing to acknowledge the storm again raging around me.

“Wonderful weather we’re having,” I chuckled, exchanging a smile with the hotel clerk. A man and two children, presumably her family, were piling towels in the lobby where the ceiling had sprung a serious leak. I tiptoed around the newly formed indoor swimming pool, lugged my back down the hallway, and fumbled as I dug around in my pocket for the room key.

A swipe and a double beep later, the door swung open. The familiar smell of must, mothballs, and cigarette smoke greeted me as I collapsed down on the bed. I signed contentedly, smiling, thinking about my truck. “Today, that was a good dent,” I said.

___________________________________

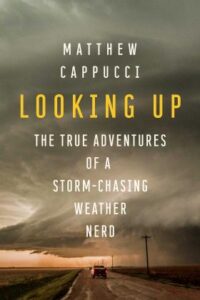

Excerpted from Looking Up: The True Adventures of a Storm-Chasing Weather Nerd by Matthew Cappucci. Copyright © 2022. Available from Pegasus Books.