How I Wrote My Memoir, One Notecard at a Time

Or: How to Fit Your Trauma in a Recipe Box

In the fall of 2008, I was high on nitrous oxide when two ideas came to me, in this order, with equal fervor: First, I needed to tell the dentist that I loved her, really loved her, like if I were to make love to a woman it would be her, as soon as she removed her hands from my mouth. Also, it was time for me to start writing again. I’d earned my MFA in fiction five years earlier and had been waiting since for an idea to land. My spaceship had come in—I would record all the bizarre stories of my Indiana family, one at a time, and call the book Weird Shit.

Of these two things, I was certain. Less certain were the circumstances of my life.

After the dentist chair revelation, I went back to work at the educational publishing company where I’d been told to “look busy” and wait for “the end.” I began writing those odd family moments as memoir flash pieces (though I thought of them then more as practice than “pieces”). Within weeks, the company folded, like so many during The Great Recession, and I discovered I was pregnant with a second child (surprise!). The next two years brought stress, little money, semi-homelessness, and moves between four states. What continued were the flash pieces. By the time I moved to Montana in 2012, where the kids and I would stay, I’d accrued over 100 pages of memoir shorts. The thing is, they didn’t feel done. They felt like a thing just getting started.

The question was: What to do with them?

At a thrift store I found a black plastic box, the kind my mother used to hold her meatloaf and tuna casserole recipes, hand-written on note cards stained with soup concentrate and worcestershire. I bought a fresh pack of 3 x 5 cards and wrote the title of each flash piece on a card. Then I made a list of not-yet-written moments I planned to tackle, mostly big Traumas and little traumas. On the flipside of the cards about new pieces, I wrote details like point shoes and first period and Virginia Slims so that when I found the time to write, I’d remember what it was I’d meant to say.

This kind of fragmented note-taking came naturally to me. My father, to this day, keeps blank note cards and a pen in his shirt pocket. My brother did the same. I inherited his truck when he died in August of 2000, and in it I found a slim notepad from the Days Inn which held, in his distinct script, a few “to do” lists, and a prayer.

Once I filled out all the note cards, I could tell by the depth of the stack that these flash pieces wanted to be a book, though I did not think of myself as the kind of person who would ever be able to write a real book. The MFA program I’d attended had not talked much about the book-making process, nor do I recall us reading many craft books. To be fair, though, perhaps I simply wasn’t paying attention. I’d started the program two weeks after my brother’s death, so I was, at the time, neck-deep in despair.

Not to worry: Writing was all practice, I reminded myself. So I would write a book as practice.

“I’d earned my MFA in fiction five years earlier and had been waiting since for an idea to land. My spaceship had come in—I would record all the bizarre stories of my Indiana family, one at a time, and call the book Weird Shit.”

I shuffled the cards around, searching for structure and order, but every time I sat down to write the book (which I now knew was not only about weird Indiana stories but also about my older brother’s suicide when I was 24 and he was 29), it felt like someone let the air out of my sentences. Every time I skirted the Big Trauma, words fell flat, my brain choked by mud.

But I kept tinkering, shuffling, writing. One day I drew a note card for a piece I’d not yet drafted with the word Volaré on one side and blue vinyl, eight track, and Paradise by the Dashboard Light on the other. As I wrote about the first car our family bought new off the lot in 1978, an idea came to me. I made a note card for each car my family had owned in my youth, then cards for my cars, then cards for my brother’s cars, including the Ford F-150 I inherited when he died. I put the cards in chronological order and, under each car, I shuffled in the corresponding flash pieces. I finally had it—a shaping device, and a way to move the narrative forward, one car (and card) at a time.

Though I had not yet read Bird by Bird by Anne Lamott, I had taken the three-year route to discover the advice she delivers so succinctly in that craft book, through a story about her father helping her brother write a report on birds which, of course, is due the next day. Her father tells her brother, “Bird by bird, buddy. Just take it bird by bird.” Which is how I finally wrote the book that had been knocking on my door since my nitrous-infused crown replacement. I wrote with intention, from beginning to end, with no clue whether the manuscript would remain practice, or grow up to be something more. I took it car by car, memory by memory.

I shuffled each card into a “done” pile as I drafted, writing the new moments, and grafting in the old ones. I’m glad I didn’t know then, while cobbling out what Anne Lamott would call a “shitty first draft”, how many times I would empty and fill that recipe box with note cards, as if my desktop were a test kitchen for a cookbook and each recipe would have to be made and re-made a dozen times. Whenever I got overwhelmed or discouraged, I returned to the box for guidance. I made notes on the go, carrying cards with me, scribbling down song lyrics, chapter titles, and car metaphors about life in my twenties and driving at night on bald tires over black ice.

The cards helped me with another thing Anne Lamott writes about in Bird by Bird: How to look at things through a one-inch picture frame in order to stay focused. If I wrote about my brother’s truck on the hot August day at the Athens landfill when I first climbed inside, I could describe the feel of the upholstery on the backs of my thighs, and the smell of dust and motor oil and cigarette butts baking in the sun at the height of a Georgia scorcher. I could write about the truck, but when I tried to write about Grief, I did a verbal face-plant. Staying focused on the details I scrawled on those cards triggered the larger feelings, gave them a target while keeping them manageable.

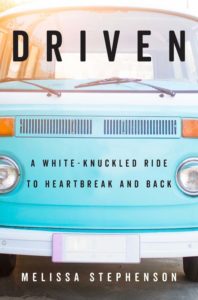

Only through attention to each one of those cards, and the micro details on the back—the one inch picture frame—did Weird Shit become more than practice. It became my forthcoming memoir, Driven.

Bird by Bird functioned like a map in the wilds of revision for me. When I found it, I’d wandered long enough on my own to truly appreciate it. I thank the stars or god or whomever/whatever it is people thank that Lamott’s guidance has made a shitty first draft of my second book go so much faster than my first. I spent about a year making notes on cards, randomly, as if it were practice (again). Then I cleared out my recipe box, organized my cards, pinned them up by chapter, and started writing. A year later, I have another shitty first draft, which could probably be called Weird Shit Two. And I know the way I did it is the way I’ll redo it: bird by bird, card by card.

__________________________________

From Driven: A White-Knuckled Ride to Heartbreak and Back by Melissa Stephenson, published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Copyright © 2018 by Melissa Stephenson.

Melissa Stephenson

Melissa Stephenson earned her B.A. in English from The University of Montana and her M.F.A. in Fiction from Texas State University. Her writing has appeared in publications such as The Rumpus, The Washington Post, Barrelhouse, Mutha, Blackbird, and Fourth Genre. Her memoir, Driven, is forthcoming from Houghton Mifflin Harcourt in July of 2018. She lives in Missoula, Montana with her two kids.