How I Became a Modern Bootlegger

“Even after 25 years in journalism, I never knew humanity the way I did working at a strip club and moving product.”

It’s a little after midnight on a cold winter night. I’m in someone else’s van, driving down a highway I’ve never seen before. I’m on my way to pick up a load of marijuana and transport it across state lines.

What could go wrong?

The trip was organized at the last minute. In situations like these, you don’t ask questions. But when a friend of a friend calls to ask if you can drive to Oklahoma for a quick drug deal, it’s hard to say no. The money is just too good.

The trip, however, is nerve-wracking. I don’t know the client, nor the person I’m meeting in Oklahoma. It’s 25 degrees outside. The van is old, and cold air rushes in through cracks in the window. I can’t seem to keep my phone charged because the cord is frayed. And where the hell is that heater control?

I’m making good time, though, considering that I’m supposed to make the connection around 3 a.m. At this rate, I should get in around 2 a.m. Once I’m there, I’m not exactly sure how it’s supposed to go down. I’m working solely on trust.

About an hour outside Oklahoma City, my client calls to check on my progress.

“Hey, you be real careful when you get down there,” my client says. “That’s the same place a guy got killed a couple months ago.”

Wait. What? The who did what now?

The adrenaline kicks in. I remember this feeling from when I was a reporter, embedded with Marines in Iraq. Your senses are heightened. Backing out is not an option. You just have to push forward, hyper-aware of every ripple and detail, every nuance in the moment that might spell trouble. Because you cannot fail. Failure in this job means jail or worse.

I’ve got bills to pay, which is theoretically why I’m out here. But to be honest, I’m also enjoying the adrenaline rush. I don’t know what attracts me to this task more, the money or the excitement. I’ll make more money on this one run than I would have working at Amazon for two months. But just as valuable to me is the feeling of vitality, of intensity, of real stakes. I feel engaged, alive. What I do has consequences. It matters. You don’t get that working at an Amazon warehouse either.

This is something they don’t tell you about criminal activity. When you’re facing economic hardship, you’re also usually facing mind-numbing, soul-destroying drudgery at the jobs that are available to you. It’s not just that they don’t pay you enough. They also make you feel dead. A lot of people turn to illegal or otherwise questionable activity simply because they want to feel alive.

*

It started for me when I got back from Iraq. I went there three times as a journalist. I got shot at, bombed, and watched a lot of people die. And then I was back at the office, writing about an infestation of woodpeckers at a local retirement village. The disconnect was severe. The alienation was setting in. But at least I was compensated well.

When a friend of a friend calls to ask if you can drive to Oklahoma for a quick drug deal, it’s hard to say no. The money is just too good.

Maybe too well, my bosses thought. After working as a journalist for 25 years, I was laid off from the paper. I had no other work experience, no other skills, and the industry was beginning its death throes, making jobs scarce. Worse, I had a bad attitude—I’d never been good at pretending to like people I didn’t, so networking didn’t exactly come naturally to me. My job prospects were limited. That’s an understatement; they were nonexistent. Soon, depression set in.

But depression or not, eventually the bills had to be paid. I spotted an ad looking for people to manage some of the strip clubs in town. I had some familiarity with that world, having covered San Francisco’s underground sex scene for a while. While not always a particularly pleasant milieu, it was at least a vibrant one. I figured that if getting paid decently for boring work was out of the question, my best option was getting paid poorly to do interesting work.

I worked as a manager for San Francisco strip clubs for two years. I broke up fights, drove out pimps and drug dealers, had a stripper throw up on me. And those are just the highlights. It was a stressful job, but there was never a dull moment. At the heart of it all were the dancers, the women who stripped in front of crowds and who would grind on strangers’ laps for money. I was in some sense a pimp, even though everything I did was legal.

Once you take the first step into the netherworld, others are easy. Your self-worth is no longer tied up in following society’s rules. In fact, it starts to get tied up in bending them. In time, the idea of a strait-laced life starts to sound a little repugnant, the idea of a job behind a desk or counter a touch insulting.

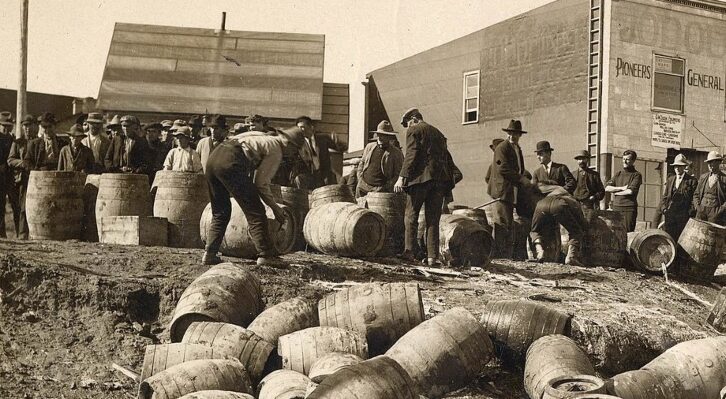

One day, I was on the phone with a friend who had moved to Florida. He was complaining about the high price of marijuana down there. He said an enterprising person could take a couple pounds of California green to Florida and make some cash. The idea appealed to me. I’m not a bad criminal—I would never hurt someone or steal anything. But I don’t agree with the laws prohibiting cannabis. Everyone I know uses it or at least thinks the laws are stupid. So I had no moral qualms that way. The only question was: could I do it and not get arrested?

I remember this feeling from when I was a reporter, embedded with Marines in Iraq.

At the time, I would have told you that my main interest was money. But then I remember something that happened before the idea was proposed, back when weed was illegal in California too. I once met an older woman at a bar in San Francisco’s upscale Noe Valley neighborhood. Her husband had died, and she had trouble making her rent. I asked how she was able to live in this expensive city. “Don’t tell anyone,” she said, leaning in and whispering, “but I sell marijuana.” I detected a note of pride in her voice, and I understood it implicitly. Poverty can’t subdue me, she seemed to be saying. I live life on my terms.

I knew some people who knew some people. The arrangement seemed pretty straightforward. Buy low in Humboldt, drive to Florida and sell high. Long drive, nice payoff, no problems. Well, maybe a few problems. As much as I didn’t want to go to jail or get robbed or shot, the idea that things might go bad sweetened the deal. It meant I had to keep my wits about me. It was a choose-your-own-adventure story.

That first drive was nerve-wracking. I kept my speed down and my head on a swivel, careful for any sign of the highway patrol. The cardinal rule of drug smuggling is don’t get pulled over. It’s not that hard: don’t drive a car that looks like a drug dealer’s car, don’t go over the speed limit, and never not be white.

After the first time, I got more comfortable with the process—but not too comfortable. That’s the other trick to staying out of jail. Never cut corners. Always take the greatest care. And never sample the product. Save that for later and buy your own.

It would be more noble to say that I smuggled drugs out of economic desperation, but that’s not true. I liked the rush. I also liked the people I dealt with, and the exposure to the human condition. Even after 25 years in journalism, I never knew humanity the way I did working at a strip club and moving product. In the dark, you see people close up. You learn who has a good soul and whose is muddy. You have to trust your gut. People will show themselves to you and it’s important that you listen.

Living on the edge brings you closer to other people, and closer to yourself. That’s why people do it. Because they want adventure, connection, and proof of their own existence in a world that otherwise treats them as expendable and interchangeable.

*

I’m overgeneralizing. There are lots of people whose lives are made worse, not better, by their involvement in illegal activity. In those cases, money is usually an even bigger factor in participation.

But truthfully, I’m not sure it’s the whole story for them either.

In time, the idea of a strait-laced life starts to sound a little repugnant, the idea of a job behind a desk or counter a touch insulting.

My friend Sarah Lauren got into sex work when she was just 19. She had grown up adopted in a conservative Christian household in Northern California, but turned rebellious upon graduation. She joined the Air Force to try to get some discipline, but that didn’t take and she was kicked out. By then, she had a drug habit and no particular way to make a living. She sought out her birth mother, who turned into a good-time drug buddy.

Sarah Lauren saw ads on Craigslist looking for beautiful young women for modeling jobs. She replied to a few and soon learned it was just code for escort work. “That was a scary moment for me,” she tells me now. “Naturally the person I turned to was my birth mother. Her response was, ‘That’s OK baby, I did it too. Everybody does it.’ That’s where my journey of sex work started.”

Sarah Lauren tells me she suffered from low self-esteem, which is not uncommon among sex workers. That, combined with her religious upbringing, had her convinced that she’d crossed a line she could never come back from, that she was permanently marred, worthless, and probably damned to hell. She worked as a prostitute for a long time, her self-hatred deepening with every transaction. For years, she didn’t think of stopping, because it seemed like all she was good for.

Her journey away from sex work was rocky. She got married and had a child. That worked for a while and life was good. But after domestic abuse, a bitter custody battle that dredged up her past, and two messy breakups, she returned to tricking. She had no other options—or, at least, that’s how it felt to her in her lowest moments. “I could just as easily have gotten a job, gone on welfare, sold pot,” she now admits. “There were a million other paths I could have taken. But at that time, in my world, that was the only choice I had.” Eventually, though, she lost control and was put under the scrutiny of child protective services.

Everything came to a screeching halt when she got pregnant a second time. She was dead set against abortion and decided to have the baby. “At that moment, I told myself I had to break the cycle,” she says. “I told myself I would make this work no matter what. I could not face the possibility that I could lose my child.” Not again.

So she found a job about two hours away from her home in South Georgia. Some days she had child care for her son, but other days she took him with her to work in an office. Some nights she had no money for gas to get home, so the two of them slept in her car and ate convenience store food. Still, she wouldn’t return to tricking, not even for the money.

Once you take the first step into the netherworld, others are easy.

Life is better for Sarah Lauren these days. She’s working as a copywriter and content editor, with a little web development and social media management along the way. Still, she faces economic hardship, and making ends meet is a struggle. I ask her if she ever thought about going back to hooking to pay the bills. “No,” she says without hesitation. “I would rather be homeless than spend one hour having sex with someone I didn’t want to be with.”

“Today, I am a creator,” she says. “I am the captain of my ship, the architect of my life and the world I live in is created by me, however I desire.”

The world seems almost designed to estrange us from ourselves. Everyone’s path back from that alienation is different. For me it involved breaking society’s rules, rejecting the tedium imposed on me as punishment for economic hardship. For Sarah Lauren, a bit of underpaid drudgery was part of her story of reclaiming her humanity.

Our journeys seem to run in opposite directions, but they share something important. For both of us, the choice to engage in criminal activity appeared on the surface to be about money. And it was. But it was also about how we felt about ourselves and our place in the world.

*

My friend Joe started selling weed when he was in seventh grade, because he wanted to get high and weed was expensive. If you sold it, you could smoke from your stash. “I had older siblings and that’s how it worked,” he tells me. “They would give me an ounce and I would roll it into joints and I would sell 80 percent of it and smoke 20 percent of it.”

He never considered whether selling weed was right or wrong. “You have to understand, my father was a bookie for over 30 years. He used to carry a gun,” he says. “I’ve seen things a lot of children wouldn’t.”

Joe has sold drugs all his life. When he was young he sold cannabis and cocaine. Later, working construction, he would do it to bring in some extra cash, especially during slow times. And when he got too old to swing a hammer, selling drugs again paid the rent. It made life livable, both because it provided needed income and because it allowed him to live life on his own terms. Selling drugs was a form of resistance to the tyranny of low-paid retail or fast food work, or whatever other mind-numbing jobs might be available to him.

Most working-class jobs require you to clock in, do what you’re told, and clock out. You could be anybody. You’re anonymous, interchangeable. There’s very little variation or genuine interaction. By contrast, Joe’s lifestyle involves a lot of person-to-person contact, and requires him to adhere to a moral code. “You’re good to me, I’m good to you,” he says. “If you’re an asshole to me, I’m going to be an asshole to you. That’s life.”

Trusting your instincts and proving your loyalty are both critical in the drug-selling business. You have to learn to distinguish friend from foe, the honorable criminals from the bottom-feeders. You come through for people in hard times, and cut ties with those who don’t return the favor. As Bob Dylan once sang, “If you want to live outside the law, you must be honest.”

It would be more noble to say that I smuggled drugs out of economic desperation, but that’s not true. I liked the rush.

The main drawback of this life, for Joe, is the judgment from people whose lives are squeaky clean. He remembered dating a girl in his twenties and really liking her. When she saw his rolling papers and discovered what he did, she called him a “pothead, scumbag, piece of trash.” It stung. His family still judges him harshly sometimes, and it hurts. But they hold their tongues, he says, “because I pay a lot of bills.”

I’ve felt the hammer-blow of that judgment before. It mostly comes from people who have never faced the economic uncertainty. They just don’t understand. Yes, it is true that people like us could get two or three jobs, completely subsume our personalities under the dictates of bosses and whims of customers. But we don’t want to, because we’re not dead yet.

The key to a successful drug business, Joe says, is to work with the right people. Generally, he does business only with people he’s known for ten years. Despite what you see in movies, there’s little violence among people in the business. For the most part, if someone lies, cheats, or steals, they are shunned and excluded from future deals.

Still, it could always turn ugly. “If you’re really unlucky,” he says, “someone with a gun who can’t accept the fact that you owe them a couple of grand will shoot you.”

Now, nobody wants to be shot. But when Joe says this, I don’t just hear fear. I hear pride, too—pride that he lives a life that requires him to demonstrate intelligence, loyalty, bravery, and discernment, or else face consequences. Joe is not nobody. What he does matters. He matters. He is my brother and I would do anything for him.

The trip to Oklahoma, which started with such intensity, ended without a hitch. It was like something out of Breaking Bad. I ran the van into a garage, waited an hour while the crew finished packaging and loading, and then drove off. Hours on the interstate, staying vigilant for threats that never appeared.

And then it was over. Not just that trip, but all of this work. All the money and adrenaline has vanished with the ever-growing legalization of this terrible drug that everyone likes so much. You used to be able to make a fortune, but that’s dried up to a trickle. Jobs at Amazon are looking better all the time.

______________________

This piece was supported by the Economic Hardship Reporting Project.

John Koopman

John Koopman spent 25 years as a newspaper reporter and editor, visiting Iraq three times as a war correspondent for the San Francisco Chronicle. A Nebraska native and veteran of the Marine Corps, Koopman is the author of McCoy’s Marines: Darkside to Baghdad.