How Horror Mirrors the Irrevocability of Grief

Gus Moreno on the Power of Sitting in Dread

I’m sitting in my car in the parking garage at Rush Hospital, reading from After the People Lights Have Gone Out, a short story collection by Stephen Graham Jones. The story I’m reading is called, “The Dead Are Not,” and it’s about a husband who notices strange beings attending the funerals of the people in his wife’s cancer support group. He’s also struggling to cope with the reality of his wife’s terminal illness. Time is ticking, as group members succumb to the disease, and partners succumb to their unbearable grief. He wonders what lies beyond this life. He’s so desperate for his wife not to leave him, he’s willing to do anything to keep her from oblivion.

The reason I’m in the Rush Hospital parking lot is because I’m visiting my sister-in-law, Carol, who was diagnosed with stage-four cancer a few months earlier. She’s someone I’ve known since I was ten. The book is supposed to occupy my time in case I walk into her room and she’s asleep from the morphine, but my head is buzzing with the first couple pages I’d read at home, and now I can’t leave my car without knowing if this guy finds a way to keep his wife alive. I know it’s a story, but maybe…

And for a small window of time, I forget I’m reading a horror story. Because the husband does uncover something, and when it’s revealed, I’m left stunned in the driver seat, staring blankly out the windshield. I feel implicated in his action, doused with it, but beneath this is a deeper current rolling through me, this realization of how much I love Carol, how much I don’t want her to die—recognizing for the first time how much I’ve been trying to negotiate with something that’s ultimately beyond anyone’s control.

*

Three years later, in late 2020, the pandemic and my personal life converged into a perfect storm of high anxiety, and the last thing I wanted was anything horror-related to enter my eyes or ears. I spent most of the time binging 90s television shows. The familiarity of Hank Hill, Bart Simpson, Carlton Banks, and The Adventures of Pete and Pete soothed my nerves. I’m sure there are people out there who used this same time locked in their homes to comfort themselves with horror instead of adolescent nostalgia, but I guess the difference has to do with why someone seeks out horror in the first place.

Every horror story is a gauntlet I willingly enter to be amazed when I make it to the other end.

For every horror fan whose closet is filled with black t-shirts of their favorite slashers, who laugh during jump scares and read King novels to help them fall asleep, there are scaredy cats like me huddled behind them, hands covering our faces but still peeking between our fingers. I’m the kid who would run out of the living room if a scary movie trailer played on TV. Goosebumps books gave me nightmares. In high school, before we started reading George Orwell’s 1984, our English teacher had us write down our deepest, darkest fears on a piece of paper.

When we reached the chapter where Winston is taken to room 101 and is confronted with his deepest fear, which is rats, Mr. Crosby read each of our answers out loud to the rest of the class, to mimic Big Brother’s exploitation of what scares us most. Everyone had written things like death or losing their parents or drowning. I was the only person who wrote “zombies.” Even in my twenties, home for the weekend from college, I went with my brother and Carol to the midnight premiere of Paranormal Activity, and when I got home, I pulled my mattress out of my room in the basement and slept upstairs in the living room.

Horror, you know, actually scares me, which is fine because—and this took me a long time to realize—I enjoy being scared. I like the attrition involved. Every horror story is a gauntlet I willingly enter to be amazed when I make it to the other end. But when I’m already in a heightened state of panic or dread, something like Midsommar or Kathe Koja’s The Cipher is not going to comfort me, because I don’t gravitate to horror to be comforted.

In a video interview with GQ, DMX breaks down some of his most popular songs. For “What’s My Name?” the GQ interviewer says, “There’s an anger in it which I always felt like—people never want to admit they are angry about something.” DMX responds by saying he’s angry all the time. He recorded the album in Miami, and had a great time in the city, but once he was in the recording booth, it was a different situation. The rage and violence just came out of him. “It’s kind of who I am,” he says. “Sometimes people want to feel worse, you know what I mean? They don’t always want to feel better.”

*

Carol passed away in 2017, and I fell down a horror rabbit hole. First, I burned through books about grief. I watched videos on YouTube of various faith leaders talking about mourning a loved one, read essays from people who lost their spouses, parents, even children, but nothing could quell this persistent hunger at the core of my being for some kind of reassurance that Carol was okay. I was hungry for meaning in her death. The grief books only made me feel like delicate porcelain. I wanted something that would at least acknowledge the pain I was in, not move past it.

It was only when I put down the grief books and picked up the horror again that I found what I was looking for—not an escape from my grief, but a way to dive deeper into it. You don’t have to look too hard to find horror movies and books that deal with loss. Because for horror to work, characters need to be compromised in some emotional way. If horror is an emotion, that means it resides in every one of us, so all it needs is a crack in the facade to seep through. We see it in other works. In John Langan’s The Fisherman, two widowers strike up a friendship over fishing to help cope with their loss. In Scream, Sidney Prescott is still mourning her mother’s death when friends start to die at the hands of Ghostface. In Hereditary, Annie hasn’t processed the death of her mother before her life is thrown into disarray with another devastating loss.

No amount of horror could have ever prepared me for Carol’s death, but it was the only genre that didn’t try to polish my grief into a stepping stone to get me back to normalcy. It validated what I was feeling, and wove it into a larger tapestry of the uncanny and supernatural, things that can’t be explained away, that shouldn’t exist in our world but do.

It was only when I put down the grief books and picked up the horror again that I found what I was looking for—not an escape from my grief, but a way to dive deeper into it.

It’s almost like we can’t accept the horror otherwise. A happy-go-lucky character is maybe too ignorant to notice any shift around them. They make quick work for our killer/monster. But a protagonist already at odds with life? They’re more cognizant, open to interpret that creaking door, that scratching sound. Pain makes them not stupid. This doesn’t stop the characters from feeling fear, but it makes them more likely to survive it. That’s one of the nuggets of wisdom in the genre. Yes, your pain is real. Yes, it can’t get much worse than this. Yes, you have every right to be scared. But the underlying metaphor in horror is that you are always capable of handling more than you could have ever imagined.

*

The most scared I’ve ever been has to be the time my wife and I went swimming with whale sharks. We were in Cancun with friends, and the resort we were staying at offered a whale shark excursion. I immediately wanted to do it, and my wife was on board because I rarely ever want to do anything. Two days later, we were up at sunrise with a couple of other guests, and a speedboat took us on a ninety-minute ride a third of the way to Cuba, where a pod of whale sharks were migrating to warmer waters.

By the time we reached the pod, my wife and I were sick from the choppy waves, having never ridden in a boat before, and realizing seconds before we jumped into the ocean that neither of us were great swimmers either. A sign on the boat highlighted the predators of whale sharks, including manta rays, blue marlins, orcas, and great white sharks. So where a pod of whale sharks were, there had to be predators nearby, right? And didn’t my wife and I just lean over the edge of the boat and spew chum into the water? And we were doing this, why again? I was seriously regretting our decision, but it was too late now.

With horror, there is no ultimate triumph at the end. Even if the characters survive or defeat the monster, there’s no going back to the people they once were. That’s what grief feels like.

I couldn’t even see the sharks in the water when the instructor told us to jump. I pushed myself off the edge and sunk like a bowling ball into open water, then frantically swam back to the rolling surface. All I could focus on was keeping my wife in front of me as we swam toward the instructor, who was a few feet ahead, the water splashing all around us, though I couldn’t tell why.

He pointed down at the water and I could finally hear him over the blood rushing in my ears. “Look down!” he was calling out.

I plunged my face under the surface, and floating only a few feet beneath me was a monster, a whale shark bigger than the boat we were on, rays of light glistening over its dark shape. My head jerked upright to the surface, and I finally saw all the dorsal fins around us. We were surrounded by whale sharks swimming close to the surface because of the rising plankton. The instructor would tell us afterward he hardly ever saw so many whale sharks in one place.

As soon as I noticed we were surrounded by these massive, sleek shapes ebbing on the surface, I was struck by the stillness of everything. The boats had shut off their engines. No one was screaming. For being monsters, with their spotted backs and huge mouths extended at least four feet wide, the whale sharks didn’t make a sound. For all the danger I felt I was in, another part of me marveled at the lack of a synth score or frightening music to play up the terror. If I was going to get caught in a whale shark’s mouth, or if one of its predators was going to catch me instead, or if I was going to drown, then I figured more of a production would have been made for my death. But there was only calm, this wise passivity in everything, and floating in the water, a great indifference permeated through me, and I felt the awesomeness of being a small thing in an incomprehensibly big world.

With horror, there is no ultimate triumph at the end. Even if the characters survive or defeat the monster, there’s no going back to the people they once were. That’s what grief feels like. I had been irrevocably changed, and no matter how many times someone said I needed to move on or let go, I knew they were wrong. Grief isn’t something you need to rush through, and no medium understands this better than horror. It sits in the dread, basks in the despair, and dares you to find buoyancy in it. Because if you do that long enough, you notice there’s a stillness in everything, and that’s how the beauty gets in.

___________________________________________________________

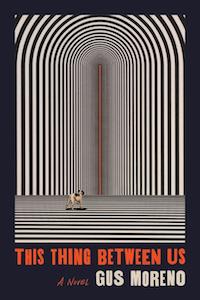

Gus Moreno’s novel, This Thing Between Us, is available now via MCD x FSG Originals.

Gus Moreno

Gus Moreno's stories have appeared in Aurealis, PseudoPod, Bluestem Magazine, and the anthology Burnt Tongues. He lives in the suburbs with his wife and dogs, but never think for one second that he's not from Chicago. His debut novel, This Thing Between Us, is now available from MCD/FSG.