How Hate-Fueled Misinformation and Propaganda Grew in Nazi Germany

“It is inconceivable that for an indefinite period the 65 million people in Germany will endure it.”

American freelance journalist Dorothy Thompson created a stir in Germany and abroad with a series of investigative stories she wrote for New York City’s Jewish Daily Bulletin in May and June 1933. She was from upstate New York but had moved to Europe in 1920, living for stretches in Vienna and Berlin. Thompson lived large. She’d been married to (and divorced from) a Hungarian writer, carried on a long-term lesbian relationship with a German sculptor, and covered European politics first for the Philadelphia Public Ledger and later as Berlin bureau chief for the New York Post. In 1928 she married American novelist Sinclair Lewis and settled down, relatively speaking, in New York City and Vermont.

Thompson had a closet full of stylish hats, a brassy manner, an intrepid devotion to work, and didn’t take guff from anyone; in the best sense of that hard-bitten professional patois of the day, a “newspaper broad.” She reported for the Jewish Daily Bulletin that postelection rampages by Nazi thugs resulted in “perhaps hundreds” of deaths and “tens of thousands” arrested.

Munich’s Völkischer Beobachter (People’s Observer) newspaper, the longtime mouthpiece of the Nazi Party, said an April 1933 raid conducted by more than 120 stormtroopers and police “took place quietly” in a Berlin neighborhood primarily inhabited by Polish Jews. Thompson provided a starkly different account, saying the assault team had entered a synagogue and destroyed part of the Torah, cut the beards off Orthodox Jews, and thrashed people indiscriminately.

She obtained the address of one victim from a source at the Polish consulate and, accompanied by her friend Edgar Mowrer—Berlin correspondent of the Chicago Daily News—proceeded to that location, climbed the stairs of a drab tenement, and knocked on an apartment door. It opened a crack.

“Who are you?” a woman whispered.

“Foreign journalists.”

“Go away!” she said, closing the door.

Thompson kept ringing the bell until the woman relented and let them inside, saying they needed to speak to her husband who had “gone away.” They continued talking, and a man gingerly shuffled into the room dressed in a hospital gown: the husband.

“It is really as bad as the most sensational papers report. . . . It’s an outbreak of sadistic and almost pathological hatred.”

“The Polish consulate told us bad things happened to you,” Thompson said. “We shall not reveal anything you say.”

“I tell nothing,” the man sharply replied. “But what the Polish consul told you is true.” He let his gown fall open. Thompson and Mowrer could see he was wrapped in bandages from his knees to his throat.

“I will tell you nothing,” he repeated.

*

Early in her reporting trip Thompson mailed a letter to Lewis, eager to share with her husband what she’d been witnessing in Germany. “It is really as bad as the most sensational papers report. . . . It’s an outbreak of sadistic and almost pathological hatred,” she wrote. “Most discouraging of all is not only the defenselessness of the liberals but their incredible (to me) docility. There are no martyrs for the cause of democracy.”

Curiously, a letter sent at the same time to her London friend Harriet Cohen—a concert pianist who kept company with widowed British prime minister Ramsay MacDonald—was less restrained. Perhaps Thompson hoped Cohen would share it with the prime minister, a high-minded pacifist. She said that Hitler’s Brownshirts were “perfectly mad” in their hounding of Jews and other quarry. “They beat them with steel rods, knock their teeth out with revolver butts, break their arms . . . urinate on them, make them kneel and kiss the Hakenkreuz [the Nazi swastika]. . . . I feel myself starting to hate Germany. And already the world is rotten with hate.”

*

In a meeting in late March 1933 with the foreign press corps in Berlin, General Hermann Göring—Hitler’s corpulent and ever-preening “minister without portfolio”—acknowledged there had been some postelection fatalities, a stunning admission. However, Göring immediately qualified his statement by adding that such “individual acts of lawlessness” were “negligible” and to be expected under the circumstances.

“Where there is planing, there are shavings,” he said, employing an odd carpentry metaphor before lapsing into public-relations gibberish. “The deaths incident to the national revolution were actually no more than there were in the normal unhappy Germany in her internecine conflict.”

The transformation of the country continued unabated. April 1 brought a one-day nationwide boycott of Jewish stores and businesses. Signs with a bright yellow circle on a black background (the international symbol for quarantine) appeared in many shop windows. On other windows Brownshirts scrawled “Jude” in red or white paint. Nazi supporters took to the streets carrying placards that read “Germans, defend yourselves! Don’t buy in Jewish shops!” The boycott proved to be more of a symbolic show of force. Almost everyone who insisted on patronizing a Jewish business was allowed to do so, but as the Völkischer Beobachter noted, “The Jews now have been made to understand that we no longer intend to bargain with them, but that we propose to tackle them in their most vulnerable spot: their purses.”

Very few Jews hadn’t already gotten that message. They’d been ostracized from most professions, were not allowed to withdraw large sums of money from their bank accounts, and as a rule couldn’t depart the country because the government refused to issue them passports. “Amongst the Jews there is a terrible despair,” Britain’s Manchester Guardian newspaper reported. “They are neither allowed to make a living in Germany nor to leave.”

In May, books were burned. All thirty of Germany’s universities held pep rally-like events. In Berlin some forty thousand Nazis gathered in the public square near the opera house, where a bonfire worthy of a Viking funeral lit up the night sky. A band played martial music. A student wearing a Nazi uniform told the crowd “un‑German” works needed to be incinerated before they corrupted any more pristine minds.

Books by Sigmund Freud got tossed into the flames, “for falsifying our history and degrading its great figures,” someone shouted. In went copies of Erich Maria Remarque’s World War I pacifist novel All Quiet on the Western Front, guilty of “degrading the German language and the highest patriotic ideal.” Books by the truckload flew through the air and onto the fire. The words of Thomas Mann . . . Karl Marx . . . muckraking American author Upton Sinclair . . . and Hugo Preuss, the man who wrote the Weimar Republic constitution.

Joseph Goebbels, Hitler’s diminutive, clubfooted minister of propaganda, stepped out of the shadows to address the book burners. “Jewish intellectualism is dead. National Socialism has hewn the way,” he said. “The German folk soul can again express itself. . . . The old goes up in flames, the new shall be fashioned from the flame in our hearts.”

*

Through the Nazi rallies, boycotts, and book burnings, the world watched and waited. Did Hitler mean all the provocative things he’d said before taking office? Would he act upon them now, or would the responsibility of governing tame his tongue and temper his politics?

The German press had no choice but to be favorable in its coverage. Yet foreign journalists, subjected to appreciably less pressure by government censors, gave the Nazis a semi-honeymoon. Dorothy Thompson, Edgar Mowrer, and a few others were writing tough pieces, but for every one of those there was the Christian Science Monitor reporter who concluded Hitler had brought to “a dark land a clear light of hope” and that “only a small portion” of Jews seemed to be suffering in the process.

In July 1933 Anne O’Hare McCormick, a roving reporter for the New York Times, got Hitler to sit for a rare one‑on‑one interview in his Chancellery office. The snake charmed her. “The dictator of Germany seems a rather shy and simple man,” McCormick wrote in her front-page story. “His voice is as quiet as his black tie,” his eyes “curiously childlike and candid.” For those Times readers who might have been wondering, Hitler “has the sensitive hand of the artist.”

He assured McCormick his focus was on creating a “program of public works,” “cutting red tape,” and fostering a strong German national identity. Unfortunately, the Reichstag had gotten in the way of his reforms, so “it has disappeared.” Same for opposition political parties.

Regarding the “fantastic” allegations of violent reprisals and of Jews being mistreated, Hitler insisted the Nazi changeover had been commendably peaceful, accomplished “without breaking a windowpane.”

*

That was nonsense, but the Nazi propaganda machine papered over such lies and the public had been cowed into silence. New laws made it a crime to disseminate “information detrimental to Germany.” Punishment could be swift and harsh. Edith Hammerschlag, a twenty-five-year-old typist at the Kodak Company in Berlin, was sentenced to eight months in prison for telling colleagues she’d heard of Jews whose eyes had been cut out by Nazis. Torsten Johnson, a merchant seaman from Brooklyn, New York, got hit with a six-month sentence. While on layover in the port city of Stettin near the Baltic Sea, he’d had a few drinks in a tavern and made the mistake of blabbering to everyone within earshot that Hitler was “a Czechoslovak Jew.”

“It is a movement based on propaganda, spectacles and insincerity, and it is inconceivable that for an indefinite period the 65 million people in Germany will endure it.”

Foreign governments maintained a cordial, nonconfrontational posture. To do otherwise might “prejudice the friendly feelings” between nations, as Secretary of State Cordell Hull delicately phrased it in a memorandum to the US diplomatic corps in Germany. Privately, there was a mix of caution and consternation. Two days after the April boycott of Jewish businesses, George Messersmith, the American consul general in Berlin, wrote to Hull about the accelerating climate of repression. “The point has been reached where it is really dangerous for the average individual to express an opinion which would not be favorable to the present regime. Even with his best friend the average German is unable to have free expression of opinion.”

*

As consul general, George Messersmith read the reports filed by Geist and other consuls spread across Germany. His own memos became more pointed. “With few exceptions, the men who are running this Government are of a mentality that you and I cannot understand,” he confided in a June 26, 1933, dispatch to Undersecretary of State William Phillips. “Some of them are psychiatric cases and would ordinarily be receiving treatment somewhere. . . . There is a real revolution here and a dangerous situation.”

Despite the ugliness unfolding all around him, Messersmith didn’t believe Hitler had staying power. In mid-November he wrote Secretary of State Hull, marveling at how an entire country could be “hypnotized and terrorized” into a psychologically altered state. How mind-boggling crazy, this Nazi blather about Aryan supermen destined to rule the world. “It is a movement based on propaganda, spectacles and insincerity, and it is inconceivable that for an indefinite period the 65 million people in Germany will endure it.”

Perhaps it seemed so “inconceivable” because other people had to do the enduring. How should one resist this Nazi mania? What price was worth paying? Who could be trusted with your secrets? With your life? George Messersmith never had to ask himself those questions. He could leave Germany anytime at will—and did so in April 1934 when President Franklin Roosevelt appointed him ambassador to Austria. Messersmith boarded a plane and left Adolf Hitler’s propaganda, spectacles, and insincerity behind. Tens of millions of Germans couldn’t do that.

One of them was Harald Poelchau.

*

On April 1, 1933—the day of the nationwide Jewish boycott—Poelchau started a new job at Tegel Prison in Berlin. It was a civil service position. He was one of nine chaplains (seven Protestant, two Catholic) attending to the spiritual needs of Berlin’s prison population, scattered over a dozen facilities. Pastor Poelchau was twenty-nine years old, thinly built with a pompadour of reddish-blond hair, and a disciple of liberal theologian Paul Tillich, his doctoral thesis adviser at the University of Frankfort am Main.

Poelchau’s father was a conservative Lutheran church pastor, but Harald felt a calling to social justice. At Tegel he ministered to some six hundred prisoners in overcrowded, austere conditions. Full portions of meat were served just three times a year: Easter, Pentecost, and Christmas. Religious services were permitted, but the chapel pews had been modified by adding chest-high wood partitions every few feet, creating cubicles that prisoners had to sit in while worshipping. The wardens, however, generally gave Poelchau a free hand. Prisoners could tend a garden he maintained on a small plot of ground outside, and the guards never examined his briefcase as he entered and left the building.

A year into the job, on April 17, 1934, Harald Poelchau’s life changed. That day he was the clergyman assigned to a condemned prisoner he had never met. His execution took place a few miles away at Plötzensee Prison, the city’s host site for capital punishments. It was as if the clock had been turned back to the Middle Ages. The defendant and three accomplices were convicted of armed robbery and murder. Just after dawn he was marched into the prison courtyard, where a judicial representative read the charges and the sentence. Two execution assistants dressed in black then stepped forward, forced the man to the ground, and positioned his neck on a chopping block. With all the dignity afforded a farm-fresh chicken, the executioner lopped off his head in one swift stroke of an extra-large hand ax.

Poelchau felt sick to his stomach. Spurting blood soiled his clothes. “The presiding officer took pity on me,” he later said, “and told me I could leave.”

Two months after that jarring introduction to the macabre responsibilities of prison pastoring, Richard Huettig, a twenty-six-year-old communist, was beheaded for the fatal shooting of an SS man. The evidence was circumstantial at best. Poelchau attended that execution too, calling it “judicial murder.” Huettig became the first German put to death by a Nazi court for presumably political reasons.

*

Death sentences traditionally had been seldom imposed, usually just two or three a year. Then Hitler came to power. There were sixty-four executions in 1933 and seventy-nine in 1934. And the new People’s Court was just getting warmed up. As arrests and convictions for crimes against the state increased, Pastor Poelchau’s work took a darker turn. He became a death chaperone of sorts. More of his ministry involved counseling and comforting the doomed. He would visit their cell in Tegel Prison during their last night: talking, praying, helping with farewell letters.

These awful hours passed mostly in silence. “How much time left?” a prisoner would ask. The pastor would check his wristwatch. Ask and check. Ask and check. As dawn approached, the prison cobbler always came to fetch the defendant’s shoes and belongings. Poelchau then accompanied him or her in the green transport van to Plötzensee Prison, lighting a last cigarette or perhaps jotting down final thoughts during the fifteen-minute ride. When it was over, he informed the family, always an awkward task, especially since the Nazis never provided advance notice of executions. A prisoner would learn only the night before that his time had finally come.

What a wretched but hallowed responsibility to be that last friendly face, to be the one trying to somehow ease the transition from here to Hereafter. It gave Poelchau nightmares, but the convictions kept coming, executioners kept sharpening their blades, and he kept staring at the dying light in anxious eyes.

As they carted Richard Huettig’s broken body away on that June morning in 1934, Pastor Poelchau had no idea how far out of control Germany would spin or that he might someday lose track of how many souls he escorted out of this world. Eventually, the numbers got too big, too inconceivable. He stopped counting and started estimating—somewhere around one thousand corpses.

__________________________________

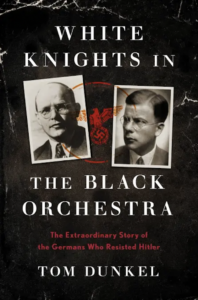

Excerpted from WHITE KNIGHTS IN THE BLACK ORCHESTRA: The Extraordinary Story of the Germans Who Resisted Hitler by Tom Dunkel. Copyright © 2022. Available from Hachette Books, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Tom Dunkel

Tom Dunkel is a Washington, DC-based journalist and author, a former staff features writer at The Baltimore Sun, and a long-time freelancer for publications ranging from The Washington Post Magazine (where his byline has appeared for more than twenty years) and The New York Times Magazine, to Sports Illustrated and Smithsonian. His first book, Color Blind, was published in 2013 by Grove/Atlantic.