How Geraldine Stutz Personified the Mid-Century Professional Woman

Julie Satow on the Early Career of a Future Icon of Fashion and Business

Geraldine Stutz stood with her slim five-foot-six frame ram rod straight, her large brown eyes staring at the floor, her thick hair pressed into a sophisticated wave, waiting nervously.

“’My dear, you are too young,” Elizabeth Penrose Howkins, the editor in chief of Glamour, told the twenty-three-year-old before her. “And you do not have enough experience.”

The pair were in Hawkins’s office on the nineteenth floor of a Lexington Avenue skyscraper, the Conde Nast headquarters, down the hall from Vogue. It was 1947, and Geraldine had been working steadily for two years, since graduating from college, in junior editing jobs at movie magazines. This was fashion, though. A position at Glamour was everything.

While inexperienced, Geraldine had preternatural confidence for her age and obvious flair. “I shall hire you anyway,” Howkins suddenly concluded with a nod, “because you have style, and that’s the only thing we can’t teach you.”

While inexperienced, Geraldine had preternatural confidence for her age and obvious flair.Geraldine could not believe her good fortune. “I didn’t know beans about the fashion business,” she said. “The only way I could get around New York was to think of the East River as Chicago’s Lake Michigan.” A girl from north of Chicago, the product of years of strict Catholic schooling, Geraldine quickly found an apartment in the West Village with several roommates and took to city life, and her job, with vigor. As associate fashion editor, Geraldine was responsible for sourcing accessories, especially shoes, that were featured in the magazine’s style stories. Her first months in New York were spent venturing out on what she dubbed “safaris,” wandering Manhattan’s avenues and side streets, peeking through store windows, stopping into shops, ferreting out “just what the Girl-with-a-Job has been hankering for… and can afford.”

Started in 1939, Glamour used the tagline “For the girl with a job,” and its pages reflected readers who, like Geraldine, were young, educated, mostly white and enthusiastically entering the workforce. The pendulum of female wage earners had swung again, from the opportunities of the 1920s, to the strictures of the Great Depression, and now back, as the World War II draft created a vacuum increasingly being filled by women workers. In addition, advances in information technologies spurred demand for office and clerical work, and as more women graduated from high schools and colleges, they had the relevant skills to fill these positions.

Meanwhile, household appliances such as washing machines became more readily available, easing the path for women to have a job and also maintain a home. Glamour was filled with advice columns on how to conduct yourself in an interview, decorating tips for living on your own, and dinner recipes that could be thrown together after a long day at the office. Under Howkins’s direction, the magazine published essays on balancing relationships and work, travelogues on where to spend your two-week holidays, and pages upon pages of colorful photographs illustrating everything from budget-friendly office wardrobes to fashionable yet functional hairstyles.

As the postwar years continued, and the ethos of the 1950s took hold, Glamour became ground zero for discussions on women’s work outside the home. There were special “Career Issues,” and articles like “Who Is Indispensable to the Boss?” that profiled female assistants to male luminaries like the journalist Edward R. Murrow and the composer Hoagy Carmichael. In one Glamour article, “Who Works Harder: The Wife Who Goes to the Office or the Mother of Two Who Stays Home?,” there were side-by-side schedules of two women, as well as an accompanying photo essay, illustrating them busily completing their days. The magazine even housed a special conference room in its Manhattan offices, where readers were invited to come and peruse the library of career pamphlets and fact sheets on women’s employment. If you couldn’t make it in person, you were welcome to write in for advice.

“A job has become more than a weekly paycheck—it’s our guarantee of confidence in ourselves,” wrote Howkins. “We know that jobs are no longer ‘amusing,’ nor a stopgap until marriage, nor a tiresome way to piece out the budget. They’re something a girl needs to know just as she knows her way home in the dark.”

Glamour became ground zero for discussions on women’s work outside the home.Geraldine excelled at Glamour. She instinctively understood the reader, since she herself was one, and she had a fashion editor’s deft eye. As part of her job, Geraldine found and collaborated with illustrators, whose work accompanied her fashion features. The most famous was Andy Warhol, who was of a similar age and was newly graduated from art school when he was hired by Glamour to draw his first shoe illustrations. It was in 1949, for a piece Geraldine edited, titled “On the Way Up: The Walking Pump.” Warhol’s drawing was a wash of warm brown, with various shoe styles hanging from ladders that crisscrossed the page at steep angles.

Next to the fashion feature were twin essays, “Success Is a Job in New York” and “Success Is a Career at Home,” and Warhol drew the same spindly ladders in brown, but with smartly dressed young women perched on the rungs, rather than shoes, the ladders rising above sketches of the New York skyline. Warhol was “straight from the hinterlands with his portfolio under his arm,” Geraldine said of the moment they met. “In so many ways, Andy came from nothing. That’s the wonder of it.” When Geraldine eventually left Glamour, she hired Warhol at her next job as well, only stopping when he grew too famous to limit himself to shoes.

At Glamour, Geraldine wrote occasional pieces and used her nick name Jerry for a byline. It was a habit she later broke, after being inundated with letters addressed to “Mr. Jerry Stutz,” including numerous invitations to clubby men’s groups. Geraldine frequently penned columns on the importance of accessories, such as how a bold scarf or a leather belt could elevate an old, tired outfit. The best accessories are not “extraneous, spur-of-the-moment purchases,” she wrote, “but adaptable wearable pieces, each one right in character and color for her clothes and the life she leads.” Being able to choose the correct accessory was a “sixth sense possessed by every really chic woman,” Geraldine maintained. It was those women “about whom a best friend or beau says, ‘You look wonderful’…not, ‘That’s a wonderful suit.’”

It was a statement that could very well have been made about Geraldine herself. In fact, her sixth sense would propel Geraldine’s career, and she eventually settled on her own trademark accessories: a turban wrapped around her head, loud bangles running the length of her wrists that jangled as she gesticulated, and a dramatic diction that sounded, inexplicably, English.

__________________________________

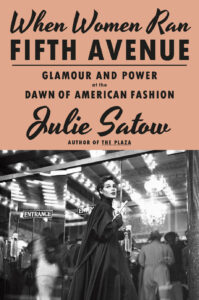

Excerpted from When Women Ran Fifth Avenue: Glamour and Power at the Dawn of American Fashion by Julie Satow. Copyright © 2024. Available from Doubleday, an imprint of Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.