How From Here to Eternity Contradicted Post-War America’s Wholesome Notions

M. J. Moore on James Jones’s 1951 Novel and Its Film Adaptation

Seventy years ago, on August 5th, 1953, the film adaptation of James Jones’s From Here to Eternity premiered at the Capitol Theater in New York City. A heat wave persisted. The theater was not air-conditioned. Nobody cared. Lines formed around the block beginning on that torrid night. A 1 a.m. screening was added to accommodate overflow crowds. The film was a blockbuster throughout the world, and the movie’s beach scene soon became iconic.

Before the film opened, James Jones’s debut novel had won for itself the 1952 National Book Award for Fiction and an international readership. It sold a half-million copies in hardcover and three million copies in paperback. Timing, indeed, was one of the critical factors. From Here to Eternity was published between the release of the controversial first Kinsey Report (1948’s “Sexual Behavior in the Human Male”) and its scandalously received sequel, “Sexual Behavior in the Human Female,” in 1953. News stories reported reactions of shock, dismay, denial, and disgust as the Kinsey Reports’ charts about extramarital sex, masturbation, and queer orientations contradicted America’s postwar self-image and its proprieties.

Jones’s novel, published in February 1951, was a febrile reading experience for millions of women and men in part because From Here to Eternity dramatized those same sexual taboos. When Sergeant Milt Warden and Karen Holmes (the long-suffering wife of Captain Holmes) plunge into their impassioned affair, they’re breaking the rules, both civilian and military. And their cinematic romp on the beach is modest compared to the written version. In the film, they’re wearing bathing suits. In the novel, Jones wrote: “They had waded, nude, out into the water, hand in hand…”

Then there’s Private Prewitt. His devotion to a sex worker creates a parallel love story balancing both the novel and the film. In the movie, Prewitt (Montgomery Clift) is seen pining away for Lorene (Donna Reed), who is presented as a “hostess” at the New Congress Club. She and the other “hostesses” are there to dance with the soldiers and share soft drinks. That was Hollywood sanitization, imposed by the censors in 1953. Readers who pick up the book after first seeing the film are often startled to discover that Prewitt’s love affair is not with a “hostess,” but with a smart young woman who fled Oregon and has mapped out her plan with precision: she’ll be a sex worker until she saves a certain amount of money, and then she’ll move away.

The love between Prewitt and Lorene is as doomed as the adulterous liaison between Sergeant Warden and Karen Holmes. It’s a wonder that Jones’s bold, rough, grimly realistic narrative managed to get published when it did (by Scribner, no less). A saturation novel in the densely textured tradition of Theodore Dreiser, the book is still shocking for its evocation of relentless hazing and the stockade’s brutalities, as well as the profanity-laced lingo of enlisted Army men. But the dueling tales of star-crossed lovers offer readers an abundance of human yearning and emotional sensitivity. It just happens that the men are in uniform.

From Here to Eternity was not the only postwar bestseller contradicting America’s wholesome notions. In 1947, an audacious debut novel called The Gallery appeared. It was written by John Horne Burns, an ex-G.I. who served during World War II in North Africa and Italy. He was the opposite of Jones, in one respect: John Horne Burns was gay.

Both authors presented intimate, intelligent portraits of characters whose quests for love bring them much suffering (as well as moments of joy and episodes of bliss). What profoundly connects their debut novels is that both Burns and Jones managed, in the epoch of Presidents Truman and Eisenhower, to write about sexual taboos, and specifically gay characters and gay encounters, despite that epoch’s rampant homophobia and the military milieus of their respective books.

Both Burns and Jones managed, in the epoch of Presidents Truman and Eisenhower, to write about sexual taboos.

In From Here to Eternity (the novel), dialogues in the bars or at Schofield Barracks emphasize the gnawing sexual frustration of soldiers whose pent-up sexuality rages within, before finally being unleashed in drunken weekend sprees. Jones portrays furtive sexual exchanges between men (sometimes for money, often to assuage loneliness, and usually soaked in alcohol) as well as blunt talk of such options.

As for The Gallery, a unique novel comprised of 17 interlinked stories, only three (“Momma,” “The Leaf,” and “Queen Penicillin”) present gay male soldiers. Nonetheless, to do so in 1947 was nearly impossible; it was also hazardous to John Horne Burns’s fledgling career.

Burns enfolds his boldest lines deep within the book. At the very end of “Momma” (the eponymous character presides over a gay bar in Naples), a British sergeant remarks to a fellow officer that they’re all “expressing a desire disapproved of by society. But in relation to the world of 1944, this is just a bunch of gay people letting down their back hair…”

Almost as risky is the book’s brazen reminder to readers that during the war, Allied soldiers and Italian civilians sexually combusted, sometimes with tremendous emotional intensity and at other times with brutal indifference. The Gallery was nominated for the Pulitzer Prize but lost to James A. Michener’s folksier Tales of the South Pacific.

No movie was made of The Gallery, and so no iconic images exist to rival the beach scene in From Here to Eternity. But in Burns’s writing, he creates prose portraits akin to those magic moments on the beach. “She bent down and laid her mouth against his temple, passing down to his lips,” Burns wrote in “Moe,” the final chapter of The Gallery, as a G.I. and his Neapolitan lover say farewell. “There was no pressure in her kiss, but it sealed a wild peace he’d been feeling with her all evening. Her kiss made him hers…”

Most of America’s World War II veterans have died. Their numbers dwindle each day. Yet in The Gallery and From Here to Eternity, John Horne Burns and James Jones offer today’s readers extraordinary, timeless truths about their tormented, commercially sentimentalized generation.

_________________________

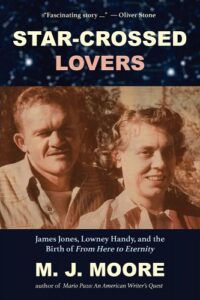

M. J. Moore’s Star-Crossed Lovers: James Jones, Lowney Handy, and the Birth of From Here to Eternity is available from Heliotrope Books.

M. J. Moore

M. J. Moore is the author of the biography Mario Puzo: An American Writer’s Quest and the novel For Paris: With Love & Squalor. Moore’s writing has appeared in The New York Daily News, Literary Hub, The International New York Times, and The Paris Review Daily. He lives in New York City.