How Dungeons & Dragons Helps Build Empathy

Marcus du Sautoy on the Joys and Benefits of Low-Tech Role-Playing Games

Christmas 1983. I was eighteen years old. Spotty. A nerd. Big into games. A present sat under the tree addressed to the family. My mom handed it to me and my sister to open. As the paper ripped apart, the image of a dragon emerged sitting atop a pile of gold. A wizard and a knight were about to engage it in battle. It looked amazing. The box declared, “You are holding a fantastic world of swords and sorcery adventures in your hands! In Dungeons & Dragons you become a mighty wizard, a fearless hero, a stout dwarf, a clever halfling or any one of a dozen other adventurers ready to explore the mazes and labyrinths of a vast and deep dungeon.”

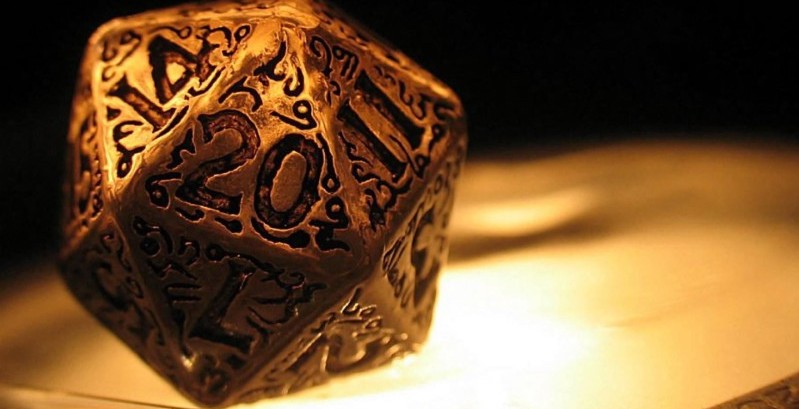

Wow! Here was my chance to live out my fantasy of being in a Tolkien story. We opened the box, excited to arrange all the pieces on the board. Except there wasn’t too much inside—just dice and a lot of rules. But what dice!

In addition to the classic cube-shaped dice of our Monopoly board, there were some of the other dice that I’d already understood were available since my forays into ancient Greek mathematics. A twenty-sided icosahedral die. A four-faced tetrahedron. A die made of twelve pentagonal faces called the dodecahedron. And finally the eight-faced octahedron. Someone had obviously done their research. One of each of the Platonic solids. I was already intrigued. But apart from the dice, there was just a lot of reading material that started to feel worryingly like an examination booklet. “You may turn over your papers now.”

Someone had to volunteer to take this exam in order to become Dungeon Master. The role seemed to require becoming a novelist and creating the setting and scenarios that the rest of the family would encounter as they descended into the dungeon. It all seemed a bit daunting until I found that part of the exam material consisted of a pre-prepared map of a two-level dungeon, plus a sort of script to help me narrate players’ journey through the dungeon. It would be my job as Dungeon Master essentially to populate the dungeon with a selection of monsters and hidden treasure. The gauntlet was thrown down. I accepted the challenge.

I spent several days that Christmas in my room studying for my exam to become Dungeon Master. Eventually I felt ready to take the rest of the family on their first adventure: In Search of the Unknown. One of the unique things about this game is that rather than commanding an army that you push around the board, like in chess, you assume an individual role. You can choose between becoming a wizard or a dwarf or a knight and then act out the adventure through your decisions in the team. This was one of the first of what would become known as role-playing games.

Perhaps board games and role-playing games like D&D tap into the very human need to sit around a campfire and tell stories to each other.

Also unique was the way the game allowed players to work together rather than against each other. Although the idea of collaborative board games wouldn’t formally appear on the scene until the early twenty-first century, Dungeons & Dragons exhibited a shift in mentality. Later collaborative games like Pandemic have clear goals, and you either win as a group or the game beats you. That is less obvious in Dungeons & Dragons. It is more like the kinds of open games or infinite games where the task is more about keeping the narrative going. There might be a dragon guarding a treasure hoard whose conquest marks a successful mission, but this game has the flavor more of reading a novel where the last page is a very small part of the whole experience. It’s about how you get to that denouement.

The game of Dungeons & Dragons, or D&D as it’s fondly known, became a phenomenon of the 1970s and 1980s, but as computer games became ever more sophisticated, the power of code to navigate your way through the multiple choices involved in exploring a fantasy world took over from the need for a human to do all the work of preparing the world in advance. Yet, powerful as such fantasy worlds as Elden Ring, Tomb Raider, or the Legend of Zelda may be, Dungeons & Dragons has seen incredible growth in the last few years. Indeed, 2020 was the game’s most successful year since it first was launched in 1974, with over fifty million players worldwide.

In contrast to the stereotypical nerdy, white, young male gamer—me—who was attracted to D&D during the 1980s, the recent surge in popularity has seen a much more diverse community being drawn to the game.

People have acknowledged how powerful an experience it is to assume a character with diverse traits and be accepted for who you are. It can offer a safe space for exploring part of your personality that you are nervous about expressing in a public social environment. With people exploring different gender identities, the possibility of playing a different gender in the environment of a game has the potential to be super liberating. My experience of assuming a female character called Zeta Siegel in the virtual world Second Life gave me unexpected insight into the sexual harassment women encounter. I still feel a little guilty about leaving Zeta frozen in the metaverse after I stopped exploring the thrills of this virtual space.

Introverts especially have found Dungeons & Dragons a very safe space to take the risk of being more extroverted. This perhaps is particularly relevant to those on the autism spectrum. It is a controlled environment, with rules and a time limit, which means you know when it will end. The game sends a message that diversity is a superpower, a sentiment Greta Thunberg promoted with the hashtag #aspiepower in connection with her diagnosis of Asperger’s syndrome.

Diversity is key to battling through the dungeons because you need people with complementary skills. If you’re all the same, your campaign is unlikely to succeed.

The internet has provided a space for hugely elaborate expansions of the concept of Dungeons & Dragons. Games like Dark Summoner and Villagers & Heroes allow players to create characters and join clans to go on virtual quests. My mother has found these worlds a fantastic escape in her old age, where she can assume the role of a great warrior and not be judged as a woman in her eighties. I expect my inheritance might include a rather splendid array of virtual armory that she has accumulated over the years. I discovered recently that thanks to her status in these games, she’d found herself a key member of a clan whose other members in real life turned out to belong to a Mexican drug cartel in Chicago and to enjoy playing the game when not dealing amphetamines. Amazing how a game can provide a common space for such diverse individuals to interact. These games all provide that sense of relatedness that our psychology craves.

Ultimately perhaps board games and role-playing games like D&D tap into the very human need to sit around a campfire and tell stories to each other.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Around the World in Eighty Games: From Tarot to Tic-Tac-Toe, Catan to Chutes and Ladders, a Mathematician Unlocks the Secrets of the World’s Greatest Games by Marcus du Sautoy. Copyright © 2023. Available from Basic Books, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Marcus du Sautoy

Marcus du Sautoy is Simonyi Professor for the Public Understanding of Science and professor of mathematics at the University of Oxford. He is author of eight books and two plays. Du Sautoy is a Fellow of the Royal Society and recipient of many awards, including the Berwick Prize and an OBE. He lives in London.