How Dorothea Nutzhorn Chased the Promise of Possibility and Became Dorothea Lange

Jasmin Darznik on the Beginnings of a Legendary Photographer

When I moved back to the Bay Area, where I’d grown up, in 2013, I could barely recognize whole swaths of San Francisco anymore, but one part of it, North Beach, was almost exactly the same. More than ever, spending time there had the feeling of a pilgrimage—a pilgrimage to the City’s past and my own. Then I heard about a place called Monkey Block, a four-story artists’ colony that had stood where the Transamerica Building is now. I immediately fell deeply in love with it—or rather, the idea of it.

Learning about this magnificent old building and its illustrious roster of past inhabitants, I was astonished to learn that so many women artists—a few known to me, many not—had made their homes in the city at the same time. I tried to imagine the conversations that had taken place in Monkey Block and the nearby streets of North Beach almost a hundred years earlier. I wanted to know what had drawn them to this place, and what sorts of lives they’d led in San Francisco.

I began casting around for people who’d been part of the world for which Monkey Block had served as a wild but steady heart. Was it a coincidence that they’d all lived here, or was there something about the City that spoke to them and, if so, had that “something” made its way into their work?

*

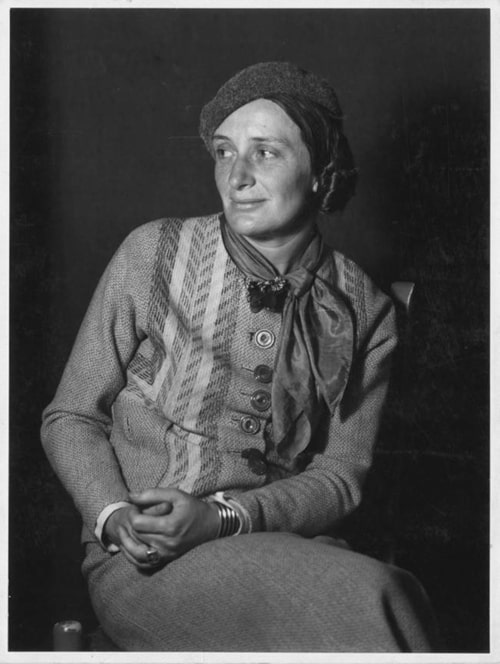

In May 1918, a 23-year-old woman named Dorothea Nutzhorn set off on a round-the-world trip. She’d been working as an assistant in a Manhattan portrait studio, but then her boss shuttered the business—a casualty of America’s entry into World War I. In a way, it was her lucky break.

For years she’d been saving money to travel, and now she could. Europe, the usual destination for a young person with an artistic bent, was out of the question, so she went west, toward California. By the time she got to San Francisco, two things had happened: she’d been robbed of all her money and she’d renamed herself Dorothea Lange.

The city she found was just a decade old, having been almost totally destroyed in the earthquake and fires of 1906. Then, as now, it was a city on the edge of the continent, a place of beauty, promise, and tragedy. In May of 1919, the month she arrived, soldiers were shipping out by the thousands from the West Coast and the Spanish flu had just begun its advance.

The bright moneyed days of the Jazz Age glimmered in the far distance, but for women, this was a time of possibility. In the first decades of the 20th century, women, particularly young women, were in open rebellion against the past. Lange had first joined this rebellion in her native New Jersey, albeit on her own terms, but its most delightfully raucous interludes took place during those first years in Northern California.

“I found myself in San Francisco,” she’d later say.

The self she found was profoundly shaped by the company she fell in with. Since 1901, nearly two decades before Lange arrived in California, photographer Anne Brigman had been trekking to the Sierra Nevada, photographing herself on the edge of a cliff like a swaggering buccaneer, or else posing nude in the crook of a wind-warped tree. 1901 was the same year another pioneering photographer, Imogen Cunningham, bought her first camera.

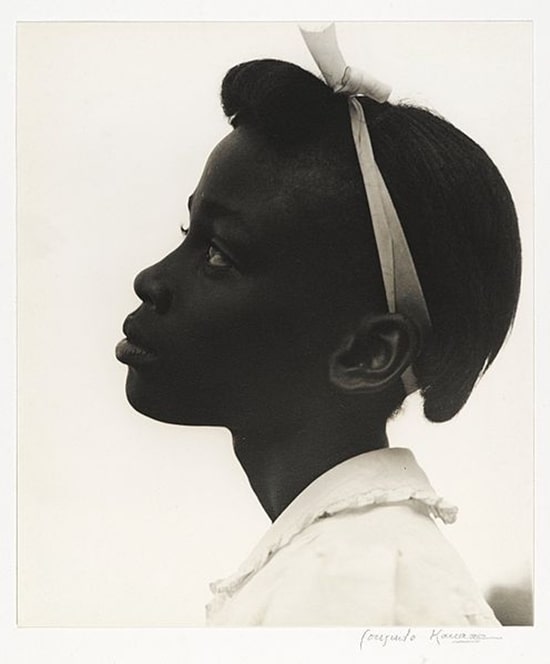

Soon enough she was causing a scandal by photographing male nudes. Eventually, her skill would earn her a place alongside Ansel Adams and Edward Weston in the pioneering Group f/64. Working in the same vibrant milieu was Consuelo Kanaga, who’d bring a radically inclusive eye to her portraits of people of color.

San Francisco had always been a welcoming place for artists, but it was a disaster of epic proportions that kicked the door open for these women photographers. The earthquake and fires of 1906 had devastated San Francisco’s artistic community. Many members set off for Carmel, which was then a sleepy coastal village, or to Berkeley and Marin County. Some went to Mexico. Others, like Lange’s own mentor, Arnold Genthe, returned to New York.

It’s from this vacuum that a band of women photographers emerged. Of necessity and temperament, they were resolved to earn their own money. During their time in San Francisco, these women not only took groundbreaking pictures but initiated and sustained connections with one another. As each woman asked what kind of pictures she wanted to take, she also faced the question of what kind of life she wanted to live, and it was in looking at one another that they began to answer that question.

Before coming to California, Lange had dipped a toe into the New York art scene, not as a participant but as a spectator. A practical young woman of German immigrant stock, she was years away from thinking, much less of calling, herself an artist. “Tradeswoman” is what she thought of herself back then. I wonder how much this owed to the sexism of the East Coast photography establishment of her youth. For all his professed modernity, the reigning king of the New York photography world, Alfred Stieglitz, didn’t bar women from his circle outright, but he might as well have, given the very small number of women whose work he chose to promote.

San Francisco had no king. What it had was a number of very successful women photographers. Imogen Cunningham, one of the first photographers Lange met in the City, was one of them. She’d attained a degree of critical recognition that was still rare for a woman in what was still thought of as a man’s profession. But that wasn’t all that impressed Lange. Cunningham had run a portrait studio in Seattle, and while she continued to do portrait work in San Francisco to support herself, when she and Lange met, Cunningham was making art photography.

The bright moneyed days of the Jazz Age glimmered in the far distance, but for women, this was a time of possibility.

Notably, she also served as an advocate and mentor for many other women photographers. She joined the Women’s Art League in San Francisco, which Dorothea Lange would also join, and became very close to sculptor Ruth Asawa, whom she’d photograph extensively.

Consuelo Kanaga also upended Lange’s notion of what photography could be and do. In 1915, at the age of 21, Kanaga had been hired as a reporter and features writer for The Chronicle—a real feat for a woman then. She soon showed a talent for photography and began contributing pictures to the paper as well. She and her friend Louise Dahl (later Louise Dahl-Wolfe) roamed the City on Sundays looking for interesting people and places—and found them in spades.

Kanaga was the first woman newspaper photographer Lange had ever met. Many years later, Lange shared her first impressions of this renegade photographer: “[She] lived in a Portuguese hotel in North Beach, which was entirely Portuguese working men, except Conseulo… She’d go anywhere and do anything. She was perfectly able to do anything at any time the paper told her to. They could send her to places where an unattached woman shouldn’t be sent and Consuelo was never scathed. She was a dasher.” Lange wouldn’t begin taking documentary photographs until 1932, by which time Kanaga had been practicing a version of that art for over a decade.

Dorothea Lange’s coming-of-age harkened back to a San Francisco where artists and writers could still arrive with nothing and make a home, where a young woman with no connections or money but heaps of grit might encounter a new version of herself. Researching and writing about her formative years, I learned that art—like the people who make it—thrives in communities. Solitude and independence are necessary conditions for most creative people, but a life of sustained artistic practice requires friendship, mentorship, and community.

In the first decades of the 20th century, women created these conditions for one another. Each of the women photographers Dorothea Lange met in San Francisco was brilliant, tenacious, and brave. Taken together, they were a force.

__________________________________

The Bohemians is available from Ballantine Books, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2021 by Jasmin Darznik.

Jasmin Darznik

Jasmin Darznik is the New York Times bestselling author of The Good Daughter: A Memoir of My Mother’s Hidden Life and Song of a Captive Bird. Her books have been published in seventeen countries. She was born in Tehran, Iran, and came to America when she was five years old. She holds an MFA in fiction from Bennington College, a JD from the University of California, and a PhD in English from Princeton University. Now a professor of English and creative writing at California College of the Arts, she lives in the San Francisco Bay Area with her family.