How Do You Write One of Humanity’s Most Intimate Moments?

Toward a Unified Literary Theory of the Kiss

Brian Turner: Over the course of several email exchanges, I asked a handful of the writers included in this anthology to think about their own internal struggles and processes when they meditate and write about moments of intimacy—specifically when writing about the experience of kissing. Basically, I sent out a small questionnaire to each of them—a kind of Kinsey Report on literary kisses—and here are some of their responses . . .

1.

When attempting to write about an intimate moment, such as a profound and meaningful kiss, what is the single most challenging aspect of it for you?

Benjamin Busch: Intensity. How do I join words to create electricity of the kind a kiss can have? I have to be dutiful to passion without concern for how I’ll be seen in its light. In this case I just didn’t think I was allowed any disguise, no protection from how vulnerable it made me. There’s often a tendency to keep confession at a distance, to use retrospect instead of introspect as a way to hide. In a kiss, we forget to do the dishes, we drive off the road, our horizon warps and blurs. There are just the two people touching.

Pico Iyer: Intimacy is exactly what we’re crying out for—because we’re missing—in our super-accelerated, short-attention-span, distracted times. So I think a writer has a chance (you could almost call it a duty) to liberate the reader from the fast-forward roller coaster on which she’s found herself and return her to that slower, more sensuous and spacious place she has inside her that has got overgrown or forgotten in our times.

It’s hard, therefore, to get the reader to sit still long enough now to pay attention to a kiss, which is a perfect example of something that needs to be slow, absorbed, and heartfelt to be exciting; but that’s exactly why we have to do it.

We live in the age of the blog, and the first-person narrative, which tempts us to forget that the personal is not necessarily the private, and that the felt is not always the deep. So in recording a kiss, I want to try to take the reader to that inner space where all thought of self is dissolved and we’re ready to let go of everything we think we know and hope we can control.

Philip Metres: Of all the kisses that I could have written about, writing about a “shut-the-fuck-up” kiss to a competitor athlete on the basketball court was probably the least likely one to choose. It induced contradictory feelings of pride and shame, and that made writing about it intriguing to me. The most challenging aspect was laying bare those layers, some of which revealed my own human failings.

Major Jackson: With great effort, I tried to navigate the borders between the literalness of a kiss and its symbolism, but also, wanting to arrive at some insightful meaning. Whenever I see young people (and it’s mostly always our youth) engaged in public acts of intimacy, I inevitably marvel at their boldness and feel the magnetic pull of intimacy.

2.

What are the pitfalls in writing intimate moments—and how do you suggest avoiding them?

Nickole Brown: The question really is this: What aren’t the pitfalls in writing intimate moments? The problem is with language—we simply don’t have the adequate words to describe the complexities, especially when there is such a vast chasm between the way an act of love looks versus how it feels. A description that’s too emotional will shorthand the experience with abstractions of love or desire, but one that’s too literal will barrage with a tangle of lips and limbs, sort of as if one might try to describe the experience of a delicious meal by placing a tiny camera in the mouth. Make the mistake of the former, and your reader will dismiss the writing as sentimental; make the latter, and a whole undercurrent of feeling is often lost or, worse, will turn your reader off altogether. In reality, the joining of two people is a flood so complicated that it seems that literature might be the only form truly capable of not just handling the sensory details but the unpredictable fires hot with memories and other associations lit in the brain during intimacy.

Philip Metres: Writing about intimate moments is as fraught as any self-representation. Now more than ever, with the avatar-level self-fashioning of social media, it’s easy to slip into creating a mere performance. Just as, when you were young, your bedroom moves were all imitations of what you’d seen on-screen, in films or videos. You’re there but you’re not there, not in the vulnerable place. You have to write past the performance and into the vulnerable place.

Sholeh Wolpé: I think when a piece of writing about an intimate moment does not work, it is because it lacks authenticity of experience. You can either translate an intimate experience, or you can re-create it. Translating a moment means: You are intellectually and factually accurate. You recount what happened. How you felt or what you saw. However, re-creating a moment for the reader requires marriage of fact with imagination. Did it feel cold? Then it was cold—even if it was 80 degrees and sunny. Was there a breeze? There was if you felt it.

3.

Among all of the kisses captured or explored in literature and art, is there one that you would point to as the North Star of them all?

Camille T. Dungy: I don’t know that I’ve ever thought about this question. It’s a good question. I do love (in a tear-my-heart-out kind of way) the scene between David and Joey in James Baldwin’s Giovanni’s Room. The intensity of emotion Baldwin describes in that early scene shadows the entirety of that novel. But that turns out not to be a happy kiss. I wish I could bring my mind to settle on a happy kiss. There is an amazing and beautifully intimate scene in An American Marriage by Tayari Jones. The kiss(es) in this particular scene I have in mind is one that I have been thinking about since I first read it. It’s a kiss that I’m glad to know someone in the world has experienced. And it’s a kiss that helped to make fictional characters feel to me like people who exist in this world.

Philip Metres: I love the curves of Auguste Rodin’s “The Kiss,” that sense of twining and twinning. You can almost see the DNA helixing through them.

ROMEO: Sin from thy lips? O trespass sweetly urged! Give me my sin again.

Major Jackson: One of the ending lines in Dorianne Laux’s poem “Kissing” states: “In a broken world they are / practicing this simple and singular act / to perfection.”

4.

What does it mean for a reader to experience the joining of two worlds, as the depiction of a kiss suggests? That is, what can we, as readers, glean or experience in the literature of intimacy?

Benjamin Busch: A moment of verse or prose that seeks to inspire human intimacy is an attempt at transference, a hope that another mind will be lit. That’s the work of a messenger. I’m offering my dream to yours, hoping that your imagination and memory enter it, subvert it, subsume it and leave it behind. I want the reader to take my place. I want my words to be the reason that happens.

Sholeh Wolpé: Stanley Kunitz says, “Words are so erotic. They never tire of their coupling.”

Camille T. Dungy: One of the things that is so tricky about describing kissing is that fine line between voyeurism (and its even less couth cousin, pornography) and what this project is working toward. When we write the kiss, when we read the kiss, we want to be welcomed into the wonder of the beauty of a world that is at the very center of the created creation. I once heard Jericho Brown say that he is a manifestation of the living God and so when someone touches him, when someone loves him, they are touching God.

Those are my words for Jericho’s, but the sentiment struck me to the core when I heard him speak it. One of the things that poetry can do is give sound to the inarticulate voice of creation. When we kiss, when we touch each other with love, we are touching the skin of creation. It’s a gorgeous thing, this liminal space both great art and great intimacy bring us to live inside. It can be easily corrupted, and it is hard to watch someone else enter that space without wanting a fig leaf or some sort of mediation, because it can be so pure and so fundamentally perfect it practically sears. But if the writing is good, the reader can be present—not just as voyeur, but as participant.

Major Jackson: Intimacy abounds in the natural world; our carnality however, is conjoined with our ability to assign meaning, and it is our imagination and intelligence that I find the most erotic. More than appeasing our appetites for titillating details that may or may not arouse, pulling back the sheets so to speak on our most private moments gives us a fuller portrait of our humanity. Somehow, too, we are wrenched toward a greater enlightened space when we can do more than delight in the sensuousness of human contact. We are gifted a storehouse of images that models closeness and affection. Who couldn’t use more of that in their lives?

5.

When writing about intimacy, is it crucial to have an element of the subversive included in the meditation?

Nickole Brown: Many contemporary artists might consider an element of the subversive necessary to make a kiss effective in literature, but I don’t agree. Shock and surprise and irony work at times to make such a sentimental and over-used topic new, but it’s not the only way. For me, I prefer something more vulnerable—deep attention and a raw, muscular kind of seeing to defamiliarize those things we’ve all seen depicted too many times. I also think it’s worth mentioning that saying a thing plainly and with your heart is worth the risk . . . Listen. We’re human beings, all pretty much wired the same way. We yearn for companionship, for love, and need to be touched. You can subvert that all you want and it may get your readers’ attention, but my guess is it won’t stick, that they won’t turn to that poem or passage again in a time of need. I’d rather encounter a weaker poem keenly felt than a clever one that leaves me cold.

Benjamin Busch: Intimacy is all subversion. Your sense of independence, your lone identity, is partially destroyed by that kind of invasion of privacy. Beyond that, in writing about it, readers take our words and construct their own version of our confessions. There should be a law . . .

6.

What makes a kiss profound? What makes it unforgettable?

Major Jackson: A kiss is profound when it feels most singular—like a new planet being born.

Camille T. Dungy: I read/heard once that new atomic studies suggest that when you come in close contact with people in particular kinds of ways certain parts of your atomic matter leave the atoms that make up you and enter the atoms that make up them. But not really. The parts are still whole within themselves, they just stretch out and are also whole within the other. After hearing/reading this, I began to understand why some people I have loved still feel like they are a part of me, even when we have not been a part of each other’s lives for a very long time.

Philip Metres: A kiss is a mere touch of the lips, but it’s the electrical field of the body and mind electrified that make it memorable, that scores it into memory.

7.

Is there a connection between lyric suspension and an unforgettable kiss? That is, when the world sloughs away and time is upended, life swirling around a moment until all that seems to exist is the kiss and the singular moment of it—does this point us toward the eternal, the spiritual, the sublime?

Benjamin Busch: We kiss each other mouth to mouth. It’s a connection at the source of sound, where our language is spoken, where we eat and breathe. A deep kiss is an attempt to join another person at their most vital point. I don’t know what gets at eternity, I’m not sure what counts as spiritual, but the sublime is at work in a kiss.

Major Jackson: Time is held at bay when one is kissing, properly. The demands and facts of our life seem to disappear and two people are their own purpose, far away from the banality of existence. Such transcendence is achieved by other means but every kiss is an echo of the very first human kiss, ancient and long-ago.

Sholeh Wolpé: I once kissed a man in an elevator at a writers’ conference. The trip between the first and twelfth floor is continuing. My knees went limp and gave way. I would have collapsed had he not held me tight against himself, not relenting a second of that kiss which—if I close my eyes right now—is still happening, there in that elevator, moving up, never stopping.

__________________________________

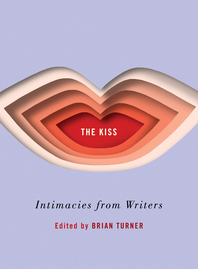

From The Kiss, edited by Brian Turner, courtesy W.W. Norton. Copyright Brian Turner, 2018.