How Do You Know If Your Short Story Should Be a Novel?

Bill Cotter Wrestles With the Right Way to Tell a Story

The list of novels that began their lives as short stories is long and well known. Jeffrey Eugenides’s The Virgin Suicides, Eudory Welty’s The Optimist’s Daughter, Jhumpa Lahiri’s The Namesake (which began as a short story titled “Gogol”), Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway (expanded from her 1923 story, “Mrs. Dalloway in Bond Street”), Jonathan Franzen’s The Corrections (which grew from his 1996 story “Chez Lambert”)—these are just a few of the most often–cited examples in the English language. There are thousands of others, of course, in every language, by writers from every generation since the modern short story arrived as a literary force in the early nineteenth century. It’s a genre in itself, almost: the novel that was born a short story.

Why does a writer decide to expand a story into a novel? The answer will differ for everyone, though I think it’s safe to say that the transformation must necessarily stem from a kind of ineffable hollowness; a sense or feeling that the story one has written is somehow wanting, or maybe belongs to something larger. The feeling, I imagine, could be a bit like homesickness, a disregulation in the innate understanding of where—or in what form—a story is to be most comfortable. If a story is in need of a heart, or a hearth, this will reveal itself to the writer eventually. Sometimes a story requires a drastic change to get home.

A transformation into a screenplay, a poem, an opera, a mime; crystallization to flash fiction or haiku. But those are true metamorphoses; we’re mainly concerned here with a kind of linear, generic expansion: from short to long-form fiction.

If a story is in need of a heart, or a hearth, this will reveal itself to the writer eventually.

I had a friend in New Orleans back in the mid-1990s whose daughter, a smart kid of five or so, was interested in the ritual and trappings of Halloween. One year she went out trick-or-treating dressed in a skeleton costume. Her older brother challenged her.

“You don’t even know what a skeleton is!” he shouted from under his Ninja Turtle mask.

“Yes I do!” she shouted back from under her skull mask. “It’s what God hitched the meat to!”

The immediacy of this imagery, and its ghoulish Art-Linkletterian construction, has stuck with me for years, and I’ve occasionally found it useful to illustrate some point or another. It seems appropriate in thinking about expanding short-form fiction. You have a story, a good narrative; a skeleton with some connective gristle and maybe a reticulum of nerves and vessels. A core spark—faint, maybe, but evident. And you have decided that it needs more. Some meat. A novel’s worth of meat to hitch to your skeleton. You just have to figure out how your barren creation is ultimately going to look. Lean, cocksure, indomitable; a Jim Thorpe of a novel? A bull, bloodied but still raging against the walls and the picador? Or an asp, hidden in the weeds by the side of the road?

At risk of carrying this Vesalian analogy a bit too far, there is another way to think about a story vis-à-vis expansion: not as a framework, but as a discrete element—a chapter—already fully formed. An organ. Something that cannot survive long without a body around it. The lone chapter dies without its surrounding novel.

It’s okay to think of story-to-novel expansion in these ways, but not much help if you actually have a story that is demanding to be something more. It’s better to have a toolbox, and a roadmap.

This might be a good spot to open a brief contextual parenthesis. I have expanded exactly one short story into exactly one novel, so my experience is limited. The story was written ten years ago. I hitched a lot of meat to it, then carved some off. That 3,000-word story transformed, over two years, into a 135,000-word novel-like work, which was then pared down to an 80,000-word novel. I had a lot of help along the way. Here is what I found useful in the process.

To start, think about whether your story is a skeleton or an organ.

Next, reread your story. Out loud if you can. Consider reading not with a critical eye, but rather as a kind of lie detector, a device whose needle spikes when it encounters something bumpy in the narrative. Anything that gives you pause, or makes you stumble, or which gives you a subtle feeling of guilt, as if there is a lie of omission. Mark these passages. These spots are ripe for examination and expansion.

Read the story again, this time with an eye strictly on character. The people who populate your story have backgrounds, friends, enemies, secrets, futures. Short stories don’t have room for all this, but novels do. It’s easiest to start with minor characters. Imagine where they might be from, who they’ve hurt and been hurt by, what it looks like under their kitchen sink.

Think about the setting. If your entire story takes place in the storage room of a bar in South Boston, then open the doors. Spill out onto Avenue D, wander into Boston, drive out to the Berkshires, fly to County Cork.

Think about whether your story is a skeleton or an organ.

Chronology and periodization. Most short stories take place over relatively brief periods—a few moment, hours, or maybe a week. Those that take place over longer periods tend to be episodic, with short scenes separated by summaries of the missing chunks of time. “Jorge turned away from daughter. When he turned back, she was gone. Four years later…,” and so on. When expanding a story into a novel, these summarized blocks of time are what get slid under the microscope, and the squirming details resolve.

Theme. Does your story deal with addiction, loss, missed opportunity, cheating? Is there a love triangle? Could these themes be expanded to form threads that plait throughout a whole novel? Could the love triangle become a love trapezoid? Could it start that way, and someone dies off?

Not every story is destined for novelhood.

Conflict. Your story has some kind of precipitating conflict that threatens to explode. We are rapt, and we read to the end to find out who stomps on the fuse or is consumed in the fireball. In a novel, the initial conflict metastasizes more slowly. Other conflicts flare. The tension builds by increments, page by page. The narrative is separated into chapters, each of which ends with some unexpected but absolutely inevitable development that will prevent us from tucking the bookmark in the gutter, shutting the book, and turning out the bedside lamp.

Remember that when writing a novel (or anything, really), you can start in media res. Write the scene that is most lustily eating at you. Write the part you’re afraid of writing. Write the chapters that precede and follow your short story.

Subplots. Maybe the essential difference between a a short story and a novel is that the latter has room for minor narratives woven into the main storyline. It’s sometimes helpful to think of subplots as existing above or below a central narrative. A subplot that exists below a storyline might be a character’s struggle with a secret addiction to gambling. A subplot that exists above could be a virulent election, a comet on the way, a pandemic, an Amber Alert. Subplots can of course coexist with the central narrative, too. The main character, in addition to being stalked by an ex-lover, is also doctoring the books for his mother’s law practice, putting off a much-needed root canal, and quietly stealing koi from his neighbor’s pond.

Preparatory experimentation. If you’ve got some anxiety about starting the process of turning your story into a novel, try storyboarding an existing work, a famous or favorite story. Steven King’s “The Ledge,” about a man forced to inch along the tiny ledge around an upper floor of a skyscraper, has always seemed like a lone chapter—an organ—and I have imagined how it could be surrounded by a novel. Same with Nadine Gordimer’s “A Find,” a harrowing portrait of an angry man who finds a diamond ring on a beach and schemes to use it to find a mate. This story is of the skeleton variety, with meat demanding to be hitched on. I like to think about the life of this terrible man, the story beyond the beach, the backstory of the ring, the themes of fury, desperation, and the erosive, timeless waves.

The most important thing to remember is that not every story is destined for novelhood. Some of the stories you’ve written are already home, self-contained and literarily durable. Choose a story you’ve written that is calling to you for more, begging for a narrative body to live in. The result may look nothing like the original, having been divided and boiled down, as Ocean Vuong puts it, “to a single red tripwire.” Or it may be entirely unchanged, nested comfortably as a discrete chapter, cozy and at home in a symbiotic relationship with the novel surrounding it.

__________________________________

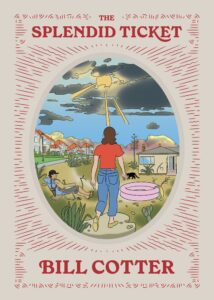

The Splendid Ticket by Bill Cotter is available from McSweeney’s.

Bill Cotter

Bill Cotter is the author of the novels Fever Chart, The Parallel Apartments, and, upcoming September 2022, The Splendid Ticket, all published by McSweeney’s. He is also responsible for the middle-grade adventure series Saint Philomene’s Infirmary for Magical Creatures, penned under the name W. Stone Cotter, and published by Macmillan. Cotter’s short fiction has appeared in The Paris Review, Electric Literature, and McSweeney’s Quarterly Concern. An essay, “The Gentleman’s Library,” was awarded a Pushcart Prize. Cotter lives in Austin with his wife, the sensational mezzo-soprano Kristine Olson. His books are for her. When he is not writing, Cotter labors in the antiquarian book trade.