When the stock market crashed in 2008, the offices closed at the legal publication where I worked. I lost my benefits, my office space, and my security, all in a single meeting. I holed up in the New York University Bobst Library for a couple of weeks as a freelance writer, scribbling reports and watching my health insurance expire. I was a single speck in a national catastrophe for writers.

According to the Department of Labor, the printing and traditional publishing sector shed well over 134,000 jobs during the Great Recession. This was part of a much larger set of losses as digital technology disrupted traditional publishing. Between 1998 and 2013, the book publishing industry lost 21,000 jobs, periodical publishing cut 56,000 jobs, and the newspaper industry shed a staggering 217,000 jobs.

After my old job folded, I camped out on the seventh floor of the library, tucked away among the American Literature shelves. I started looking for clues on how writers survived the Great Depression. In the stacks, I found You Can’t Sleep Here, a novel written in 1932 by a 20-year-old Hungarian immigrant named Edward Newhouse. His book tells the story of a young newspaper reporter fired during the early days of the Great Depression who sleeps in a tent city along the East River and who showers in a bathroom at the New York Public Library.

The reporter paces up and down the side of Central Park at sunrise, hoping to get the first look at the want ads before thousands of other unemployed people. “I had to walk till 55th Street before one of the newsstand men would let me look into the want ads.” A quiet desperation permeated every line of Newhouse’s story. I couldn’t stop reading.

US unemployment peaked at 25 percent while Newhouse was writing his novel. Economic catastrophe led to the unprecedented closing of hundreds of magazines and newspapers. Library budgets were slashed. Chicago and Philadelphia both reported that their book buying budgets had been completely cut for 1933. The NYPL saw its budget cut from $256,000 to $120,000 in the same year.

I came across a photograph of a line outside a Depression-era employment agency. The men were wearing suits left over from better times, waiting in an endless chain. They were resigned souls shuffling towards a wall covered with job posters that had already been filled. A New York Times columnist poked fun at the plight of struggling authors in a 1931 column called “Our Lazy Writers”: “Our younger writers, possibly due to the greater rewards of success, make a great how-de-do about turning out a fairly long novel once every two years; and for this they must have European trips, winters in California and Florida, summers in Vermont and Maine, city penthouses and what not . . . Can it be that American authors waste too much time attending literary teas?”

In You Can’t Sleep Here, the novel’s young hero struggles to make a living as a writer. “The story sounded funny but the situation wasn’t,” Newhouse wrote, as his hero finishes yet another story he can’t publish. One character chides the young journalist: “Anybody who really wants to work can find a job,” and you can feel Newhouse’s fury radiating through the pages.

“Anybody who really wants to work can find a job.” The old lie is still alive. Internet job boards have created the illusion of boundless opportunity during our Great Recession, but I soon came to realize, like everybody else, that automatic email programs did most of the responding. This was new corporate machinery to avoid discrimination lawsuits and to create the illusion of agency and opportunity. I read a story about a thousand people applying for a minimum wage job at some online publication. It was easy to imagine us all as that throng of unhappy men in the Great Depression photograph, shuffling toward some imaginary goal.

Scattered among those job postings were the realities of the gig-economy. Apps had broken transportation, food delivery, and housecleaning into discrete units that could be performed by temporary workers around the country. In a quest for endless growth, these companies turned to automated strategies to find gig-based employees. For a year straight, I received a stream of job emails promising to “Supplement Your Writer Income.” These job postings had nothing to do with writing. They were part of an enormous automated campaign to find more Uber drivers around the country, feeding the same subject line to writers who couldn’t make ends meet anymore. These job descriptions had nothing to do with expertise in the field: “Drive with Uber and earn money anytime it works for you. Driving is an easy way to earn extra, and it’s totally flexible around your schedule. You decide when and how much you drive.”

This “Supplement Your Income” recruitment strategy also worked for Postmates, a food delivery company that depends on a fleet of gig-economy drivers. That company flooded job sites with automated and generic job postings with the same structure: “Teacher? Earn Extra Income—Drive for Postmates!” There were hundreds of postings targeting everybody in our gutted workforce with the same “Earn Extra Income—Drive for Postmates!” structure: Receptionist? Maintenance Technician? Social Worker? Medical Technician? Administrative Assistant? Call Center Representative? Registered Nurse? The flurry of job title queries highlighted the fractured state of our post-recession economy. Millions of workers needed to supplement lower paychecks with gig-economy work.

As more and more workers have turned to the gig-economy, transportation earnings have steeply declined. The JP Morgan Chase Institute published a 2018 report about the state of our “online platform economy,” analyzing how 2.3 million Chase checking accounts processed gig-economy earnings—crunching 38 million payments directed through 128 different online platforms from 2012 to 2018. During that period, “transportation sector” gig-economy drivers for companies like Uber or Postmates saw earnings decrease by 53 percent. The gig-economy gave our post-Great Recession economy the illusion of progress, but we filled the landscape with unreliable jobs offering diminishing pay.

“Our younger writers, possibly due to the greater rewards of success, make a great how-de-do about turning out a fairly long novel once every two years.”We officially emerged from our nationwide recession in 2009, but the situation facing contemporary writers has not changed. The newspaper and magazine jobs that disappeared were never replaced. The bookstore chain Borders closed for good in 2011, erasing nearly 10,700 bookselling jobs. The American Library Association noted that 55 percent of urban libraries, 36 percent of suburban libraries, and 26 percent of rural libraries cut their budgets in 2011. In the same survey, librarians said that job-search services were most in demand at the library, but that 56 percent of the libraries didn’t have enough resources to meet the demand.

Wherever I looked, I discovered that Newhouse had been there before me, describing what he called “the crisis generation”:

I was the crisis generation who had never been absorbed into the industry or the professions. Depression. Periodic dip. Economic cycle. Normal course of events. Aftermath of speculation. Act of God. We had all the old problems … but we also had something new, the passing of economic insecurity. We college and high school and public-school graduates were certain of our economic future. The pile of lumber and the cement under the billboards was [our] immediate future. The public comfort station down the block and leftover buns at the automat and hourly super- vision by twirling bats were our certainties.

The Crisis Generation. That phrase guided me through the next few years. I paid 50 dollars to get a copy of Newhouse’s out-of-print novel so I could show it to everybody I knew. Like some misguided missionary, I’d show it to people and say, “See? See? He’s talking about us!” His book felt like a bomb with a busted timer that had stalled back in the 1930s and had been stuck on a dusty shelf for 80 years, losing none of its dangerous potency. I wanted to fix the timer and blow something up all over again.

Even so, researching these pages, I saw the tremendous class privilege that helped me survive this long as a writer. As a white man from a middle-class family, I had a certain level of security and privilege, a safety net that cushioned me from the worst parts of the recession. Even though I chose a turbulent profession, I fared far better than millions of Americans who lacked my opportunities. Robert Frank described this privilege in his 2009 New York Times essay, “Before You Protest, Thank Your Lucky Stars.” He wrote: “People born with good genes and raised in nurturing families can claim little moral credit for their talent and industriousness. They were just lucky.”

Throughout the Great Recession, the media industry depended on the work of writers of privilege. In a 2016 interview, Shane Smith, executive chairman of Vice Media recalled the early days of his digital publication: “There was a time when we were a trustafarian commune, and that was fun, that was good,” he reminisced. The Urban Dictionary defines trustafarians as “privileged white kids who subscribe to the hippie lifestyle (because they can) since they have no worries about money, a job etc.” Built by these industrious upper-crust workers, the company’s value has since ballooned as high as $5.7 billion and now pays top salaries.

I never enjoyed a trustafarian lifestyle, but I survived the recession with a series of steady writing jobs—including an unpaid internship at a glossy magazine. How many writers missed crucial digital journalism opportunities because they lacked the financial security required to enter the profession?

In 1938, a book called New York Panorama captured a similar calculus that took place during the Great Depression:

The few writers who starved it out until fame reached their garrets have been memorialized in many romantic biographical sketches; but of the many who were forced by want to abandon their literary aims no record exists. In New York City, where struggling authors are to be found in greater numbers than anywhere else in the country, the depression of the early 1930s had unusually severe effects, and there was a united demand that the Federal government should include in its work-relief program a plan to employ the writer in work suited to his training and talent.

My book is dedicated to the stories of poets, novelists and journalists who never made it. My bookshelves have always been filled with underdogs, because I still remember the uncertainty of my early days as a writer. Our canon should celebrate more than just the lucky few writers who managed to survive the Great Depression with their reputations and lives intact. We should remember the writers we left behind.

*

The New Masses

Alison Dinsmore, the daughter of Edward Newhouse, sent me a photograph of her father. Newhouse looks sly in the picture. His fedora is tipped at a hard-boiled angle. His trenchcoat collar is popped up to keep out the cold. He peers over his shoulder. He is the scrappy reporter already looking out of the frame for the next story. He does not smile, instead keeping his mouth tight and serious.

Henry Ford drove Newhouse crazy. The young novelist spent his early twenties hanging out with literary Communists around the city, and the capitalist icon became a clear Depression-era target. The Depression was Ford’s opportunity to build an automobile empire on the backs of a non-unionized workforce.

While writing You Can’t Sleep Here, the young reporter stewed over a newspaper clipping that he saved from 1928. As the American economy unraveled, the European press confronted the automobile mogul. Ford laughed off a question about reports of breadlines in America: “It is curious that we do not hear these things in the United States . . . If there were bread lines, they must have sprung up since I left New York six days ago.” Newhouse used an excerpt from that same newspaper article as the epigraph for his novel, a quote describing the celebrity industrialist and his wife dancing on a cruise ship bound for Europe: “Seizing his wife around the waist, Mr. Ford led off with a waltz and everybody joined in . . .”

The rich danced while the workers paid the price.

The hero of Newhouse’s book is Eugene Marsay, a name that combines two characters from novels by Honoré de Balzac. Eugene was based on Eugene de Rastignac from Le Père Goriot, a bold student in Paris who had a “desire to fathom the mysteries of an appalling condition of things, which was concealed as carefully by the victim as by those who had brought it to pass.” Henri de Marsay, on the other hand, “was aristocratic, a noble, a dandy, dauntless, highly skilled, fearless. In Hungarian, [Marsay] is a highly aristocratic name.”

The whole time I struggled to make it as a working writer, I was constantly aware of how many people were willing to do the same work I was doing and how many of them would write for free.Sharing characteristics of both Balzac characters, Eugene Marsay is a member of the newly unemployed middle class, struggling to understand how these “appalling” changes have occurred in America.

When Franklin Roosevelt took office in March 1933, he deconstructed Ford’s argument in a remarkable speech. His inaugural address blamed failed banking leadership, unjust distribution of national resources, and ruthless businessmen for the Great Depression. He made an urgent plea that still resonates in our own time:

The rulers of the exchange of mankind’s goods have failed, through their own stubbornness and their own incompetence, have admitted their failure, and abdicated. Practices of the unscrupulous money changers stand indicted in the court of public opinion, rejected by the hearts and minds of men. True they have tried, but their efforts have been cast in the pattern of an outworn tradition. Faced by failure of credit they have proposed only the lending of more money. Stripped of the lure of profit by which to induce our people to follow their false leadership, they have resorted to exhortations, pleading tearfully for restored confidence. They know only the rules of a generation of self-seekers. They have no vision, and when there is no vision the people perish.

The line which is remembered from Roosevelt’s speech today is, “The only thing we have to fear is fear itself,” but the president also called for new business ethics, job reform, and redistribution of resources. “The joy and moral stimulation of work no longer must be forgotten in the mad chase of evanescent profits,” he said, chastising Henry Ford and his cohorts.

Newhouse finally found a job in the summer of 1933. A magazine called The New Masses assigned the broke, young reporter several stories. First published in 1926 and running until 1948, The New Masses was an early outlet for radical writers and unionized workers, featuring some of the most famous voices to emerge from the Great Depression, including Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, and Langston Hughes. While the journal began as a monthly, it would become a weekly paper during the Depression in an ambitious attempt to reach a new generation.

For an early assignment, the magazine sent Newhouse into the hellish depths of the Commodore Hotel to cover a service worker strike. At the time, the luxury hotel was the biggest in the Grand Central neighborhood, counting 2,000 and 28 stories. The hotel staff toiled in an underground complex five stories deep. Subway trains rattled by alongside them. The owners installed a mammoth air-conditioning system, a modern wonder that cooled patrons on the floors above ground. However, in the bowels of the hotel, the cooling system pumped deadly gases straight into the unventilated laundry complex. Newhouse met two women who had collapsed on the laundry floor after inhaling fumes. The foreman brought them upstairs until they recovered consciousness and then sent them straight back down to the machinery.

Newhouse railed against a world where a hotel worker made $1.25 a day while nearly choking to death on coolant fumes. One foreman made a point of lurking around the bathrooms, bursting in when his female employees stayed past the five-minute break limit. Newhouse called it the “merciless speedup.”

I read a story about a thousand people applying for a minimum wage job at some online publication.Companies in the 21st century have been adopting similar “speedups”: trimming salaries, breaking unions, and pushing for longer hours, capitalizing on the floundering economy. A 2011 investigative report in The Morning Call shed light on punishing conditions inside an Amazon warehouse in Pennsylvania:

Workers said they were forced to endure brutal heat inside the sprawling warehouse and were pushed to work at a pace many could not sustain. Employees were frequently reprimanded regarding their productivity and threatened with termination, workers said. The consequences of not meeting work expectations were regularly on display, as employees lost their jobs and got escorted out of the warehouse . . . During summer heat waves, Amazon arranged to have paramedics parked in ambulances outside, ready to treat any workers who dehydrated or suffered other forms of heat stress. Those who couldn’t quickly cool off and return to work were sent home or taken out in stretchers and wheelchairs and transported to area hospitals. And new applicants were ready to begin work at any time.

Amazon reformed its warehouse policies after this story broke, but it raised a difficult question for activists: how do you fight an online retailer? In 2011 and 2012, the nonprofit American Rights at Work staged a Cyber Monday boycott attempting to sabotage Amazon’s crucial holiday sales. The group described working conditions in Amazon’s fulfillment centers:

Workers in shipping centers who fulfill online orders are asked to grab items for boxes at unsustainably high speeds. In many cases, workers are required to collect 1,200 items in a 10-hour shift, or one item every 30 seconds. If employees can’t keep up, they are disciplined or fired . . . Workers have to continuously cross great distances inside the massive warehouses. ‘Pickers,’ who locate and collect items for shipping, reportedly walk on average between 12 and 15 miles every shift. Despite some items being football fields apart, workers are expected to maintain the same frenzied pace.

Amazon entered these national controversies with a powerful advantage: they have no physical store locations that activists can target at the height of the holiday season. Protestors cannot reach the customers they wish to confront. Allentown, Pennsylvania’s newspaper, The Morning Call, covered the boycott in 2011, estimating that Amazon lost 12,600 customers during the action, which cost the online retailer $9 million. Those protests barely dented Amazon’s holiday sales. In January 2013, the company noted that net sales had increased 22 percent during that period—totaling a whopping $21.27 billion for the fourth quarter of 2012.

In the 1930s, the Food Workers Industrial Union represented hundreds of Commodore Hotel employees, launching what Newhouse called a “venomous, bitter and desperate strike” that dragged on for ten weeks in the streets of New York City. The union relief committee could only feed the unpaid strikers with dry bread. Newhouse stalked the picket line outside the Commodore Hotel, growing angrier and angrier as he walked: “[Strikers] appear each day with hundreds of other workers who are getting their first glimpses into the magnificent tropical lobby of the bull-necked business men whose linen they launder in the subterranean inferno.” Newhouse recorded hotel detectives and cops beating strikers senseless. His prose smoldered with rage. He was a young writer finding his voice during an American disaster.

By August, Newhouse had also landed a gig writing a sports column for The Daily Worker. This labor magazine was two years older than The New Masses and was founded by American Communists in Chicago. The editors moved the paper to New York City in 1927. With income from both papers, Newhouse scraped together a living.

Newhouse described himself as a radical during these early years:

as far back as I can remember I have been accustomed to think of myself as a Communist … The great part of my activity in the Communist movement has been literary. Alternately I worked on the staffs of the Labor Research Association, The New Masses and The Daily Worker. I was a charter member of the first John Reed Club which started in 1930.

One day, after reporting on the ongoing tribulations of the workers outside the Commodore Hotel, Newhouse toured its upper reaches with a chubby wool-manufacturing executive who was there for an industry conference. While strolling past “tropical birds, the ornate vases, jewelry shop,” the mogul complained that his daughter had bought $9,000 in dresses during a recent trip to Europe. “The girl has to be taken in hand,” he said. Pausing to buy a stuffed rabbit for her, he told Newhouse to forget about the strikers: “Don’t pay any attention to them . . . I don’t. Those people don’t know when they are well off.”

*

Publishing’s First Strike

Within a year, the New York City strikes had spread from farmers to factories. Service workers and even white-collar workers were ready to strike. In June 1934, Newhouse joined a ragtag group of employees from the Macaulay Company, marching in one of the first publishing-industry strikes. Camped out at Fourth Avenue and Twenty-Seventh Street, the picket line protested the firing of a bookkeeper and Office Workers Union member. Eleven employees walked out, making a very public scene in the crowded neighborhood. The strikers had a long list of demands, some of which reveal how rudimentary working conditions were compared to today:

All abuse and tyranny on the part of the employers must stop.

Employees must be permitted the use of sufficient electric light.

The installation of electric fans in warm weather.

Employees absent because of illness for a period up to ten days should receive full pay.

No discharge without either two weeks’ notice or one week’s salary.

Workers employed by the company for a year or longer should receive two weeks’ vacation.

F. Furman, the president of Macaulay, blamed the firing on “economy and efficiency,” and said he would never take the bookkeeper back. At the end of a New York Times article about the afternoon strike, Furman threatened to “re-staff” if the demonstration didn’t end soon. He would be in for a long, long summer. The next day, the picket line swelled to 36 writers. A thicket of protesters blocked Fourth Avenue foot traffic and attracted swarms of reporters. The cops showed up and got drawn into an argument with a Guggenheim fellow about blocking the street. Shortly after, the police trucks arrived, hauling away 18 writers including a New Republic editor and a New Masses editor, Mike Gold.

The poet and novelist Maxwell Bodenheim had once held publishing contracts at Macaulay. He described the publisher’s neighborhood in his novel, Slow Vision:

Madison Square Park and its environs showed neither brightness nor comradeship. People flew along, looked at one another with suspicion, or aloofness. A frowning exhaustion was on most of the faces and many of the others—faces of drones, or worldly men and women in good clothes—were inordinately self-centered and showed not a scrap of interest in the human beings passing them.

The police shipped the writers and editors they arrested to Yorkville where they spent two hours in jail, singing “The Star-Spangled Banner” together in the cells before being brought to court. A cop explained that the protesters had peacefully occupied the street with no pushing or shoving, and then the judge sent everybody home. They left a pile of cardboard signs on the courtroom floor. The next day, the protest swelled, with 23 more protestors arrested after a long day on the picket lines, including an editor, a publicist, and an actress. This was the last straw: a lawyer showed up and negotiated a truce between Macaulay and the Office Workers Union.

Everybody knew the Depression-era excuse of “economy and efficiency”: it justified mass firings and all sorts of workplace abuses.Everybody knew the Depression-era excuse of “economy and efficiency”: it justified mass firings and all sorts of workplace abuses. With unemployment at 25 percent, employers could manipulate workers with ease. The publisher knew he had workers by the throat. As a testament to his power, only half the staff at the small company had even gone on strike while the other half kept working. The company quickly hired temporary workers from the sea of the unemployed to fill the strikers’ spots.

The whole time I struggled to make it as a working writer, I was constantly aware of how many people were willing to do the same work I was doing and how many of them would write for free. We were an unlucky generation, squeezed between technological change and economic collapse. We had no place to go, and no bargaining chips. In 2002, 10 percent of the traditional publishing industry was represented by unions, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. By 2012, only 4 percent of all employees had union support.

The aughts peeled back more layers of legal protections and workplace rights—taking us back to Depression-era conditions. By prioritizing “continuing to work” over taking a stand on pay and conditions, we all contributed to this new reality. I have never wanted to do anything else with my life except write. I fought bitter battles to hold on to my small corner of the publishing world while trying to ignore the ways in which we are all accountable for the state of the industry in which we work.

In September of 1934, the president of Macaulay fired three union leaders working at his publishing house, setting off an even larger wave of protests. Edward Newhouse joined the demonstrations once again. The strike committee telegram was sent directly to President Roosevelt and read: “we earnestly call upon you to enforce your guarantee to the workers of this country.” Within days, other writers called for a boycott of the publisher. The famous radical novelist John Dos Passos wired his own support from Los Angeles, attaching the signatures of 13 other authors: “We urge all writers to refuse to adapt Macaulay books for the screen and to have no dealings with your company until the writers fired for union activity are reinstated.”

In a display of cross-industry solidarity that seems unimaginable in today’s business climate, employees from all around the city joined the Macaulay strikers, including publishing professionals from Macmillan, Vanguard Press, Charles Scribner’s Sons, and The Viking Press. In a New York Times interview, Macaulay insisted it wasn’t his fault: “We are all in the same boat … the depression gives me no choice but to cut my staff. My position is no different from that of other employers who have had to do the same unfortunate thing.”

The situation at the company did not improve. Macaulay fired four more union workers and refused to budge when workers launched a second strike in September. The New York Regional Board ruled in the workers’ favor, but the publisher successfully appealed to the National Labor Relations Board. The federal decision eventually ruled that since the strike happened before the National Recovery Act was established, the rules preventing employers from firing labor organizers had no authority over the publisher.

Macaulay won in court, but the damage had already been done. Writers now knew they could stand up and fight. The New Masses was enthusiastic: “it was the first strike in publishing history. It destroyed forever the notion that white-collar workers are constitutionally averse to using the tactics of the more class-conscious manual workers.” The New Masses began investing in strike coverage, hiring Newhouse to cover the growing unrest in New York City.

*

Proletarian Literature

Joseph Freeman, the editor of The New Masses, praised Newhouse’s novel You Can’t Sleep Here for its focus on “unskilled intellectuals” like newspaper reporters and other “wage slaves of capitalist arts and letters.” In his review, he described a dilemma familiar to bloggers, citizen journalists, and other internet artists:

. . . in the best of times, such members of the intelligentsia are migratory workers; they drift from jobs; they have neither the training nor the stability of engineers, physicians, lawyers or scientists. They are the first to be declassed by the crisis and pushed into the ranks of the proletariat. In times like these, it means into the ranks of the unemployed proletariat.

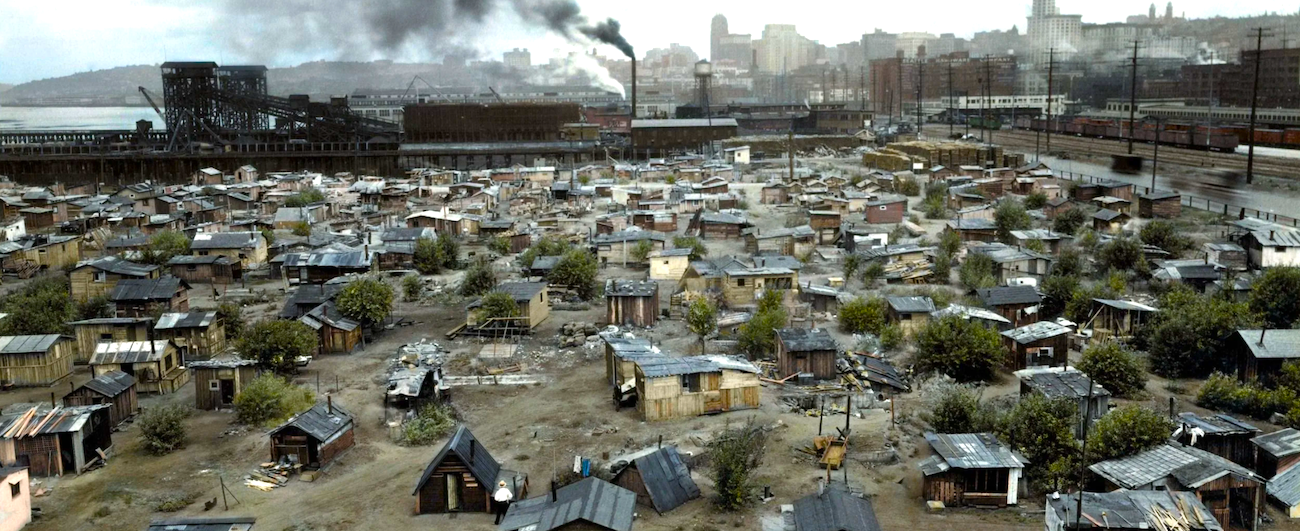

Newhouse literally camped out among the “unemployed proletariat” in an East River Hooverville, one of several tent cities scattered around New York City—encampments nicknamed after President Herbert Hoover who oversaw the economic crash of 1929. The homeless men drew water from a fire hydrant 200 yards away from the camp, carrying drinking water in pots, pails, buckets, and cups back to their shacks. Firewood was currency, scavenged inside the biggest city in the United States. Men pushed baby strollers full of firewood around town, selling kindling and earning half a dollar a day.

The reporter found homeless veterans, actors, boxers, mechanics, and workers of every stripe. When a family had to decide between children and cousins, sharing and starvation, these were the sorry souls who didn’t make the cut.A New York Times investigative report about Hoovervilles counted some 2,000 men, women and children living in tent cities inside New York City. The reporter found homeless veterans, actors, boxers, mechanics, and workers of every stripe. When a family had to decide between children and cousins, sharing and starvation, these were the sorry souls who didn’t make the cut. The unluckiest men slept in boxes alongside the huts. One homeless man dug a hole straight into the frozen earth, building a wooden roof over this grave. These nightmare towns sprang up all around New York City that winter. On Houston Street and Broadway, five people camped out in an empty lot on the corner, using the brick wall of an adjacent building to block the wind. They insulated the walls with rags.

Newhouse wrote all of these men into You Can’t Sleep Here, railing against the world that pushed these men to the margins. His hero stayed proud and wouldn’t accept charity from his socialite girlfriend, opting to sleep in a Hooverville instead of taking shelter in her pampered world. At the climax of the novel, the homeless newspaper reporter turns down a cushy magazine job so he can stand beside the squatters in the East River camp. His decision seems self-destructive to his middle-class friends. He is beaten bloody and gassed by the cops while defending these flimsy houses.

But Newhouse backed up his story with true accounts of how the government cleared tent cities around Manhattan. In 1933, the Sanitation Department steered a red wrecking truck through a Hooverville squatter camp called “Hardluck-on-River” on the East River at ten in the morning. Flanked by 15 workers and 5 cops, the city superintendent commanded the 250 men living there to evacuate the site.

The New York Times wrote about the attack:

. . . there was no revolt, no resistance. The men turned back into the ramshackle driftwood, tin and linoleum shacks to pack their few personal possessions. A few of the more stolid types—eleven nationalities were represented in Hardluck—loaded their quilts and things on go-carts and headed for nowhere in particular. All morning and up to 4 o’clock in the afternoon the wreckers tore down the makeshift dwellings with the great hooks set in the rear of the red trucks. The campers sat on the edge of the pier and looked on, with a pathetic melancholy not unmixed with curiosity in the working of the juggernaut.

In Newhouse’s novel, however, the homeless men refuse to leave the shacks they’ve built, so the police descend upon the camp. They axe open a crack in the locked doors and pitch canisters of tear gas inside the houses. Newhouse’s hero gets a face full of tear gas, a memory drawn from his time on picket lines, from attacks at factories, and from breadline riots: “Maybe you have been insane for one period of your life. Do you remember the moment before you went mad or didn’t it happen all of a sudden? Or maybe you have had fever dreams of a particular kind. Or is it possible that your dentist may have gone insane and began drilling your eyeballs instead of your teeth?”

Newhouse deconstructed the world around him, rewriting his own career as he took part in historic events. But he was also part of a larger literary movement. Before the Great Depression, Mike Gold called on writers at The New Masses to produce a new kind of fiction, an idea he labeled “proletarian literature.” In his essay, he described the range of work he hoped to include:

letters from hoboes, peddlers, small town atheists, unfrocked clergymen and schoolteachers. Everyone has a great tragicomic story to tell. Almost everyone in America feels oppressed and wants to speak out somewhere. Tell us your story. It is sure to be significant … Let America know the heart and mind of its workers.

His letter to readers spawned an entire literary movement. In The Radical Novel in the United States, the literary scholar Walter Rideout counted 70 such novels published between 1930 and 1939. Almost all these novels have been forgotten today, but Rideout’s book counted novels by Henry Roth, Josephine Herbst, James Farrell, and Richard Wright. For a few years during the Great Depression, Newhouse’s You Can’t Sleep Here became one of the most well-known examples of the genre, though the book has been out of print ever since.

_________________________________

The Deep End by Jason Boog is available from OR Books.