How David Foster Wallace Anticipated Netflix’s Digital Gatekeeping

Stuart Jeffries on the Algorithm and the Illusion of Choice

In Infinite Jest, David Foster Wallace imagined two new television technologies—neither of them as liberations from the flow of broadcast TV, but as superior means of controlling couch-prone viewers. He also imagined broadcast TV being replaced by Interlace TelEntertainment, a company from which cartridges could be bought or rented on demand and played on home cinema systems. The “on demand” invited customers to suppose that they were controlling the supply and curating their entertainment.

Interlace TelEntertainment, in its essentials, was Netflix, the home-entertainment streaming service that was launched in 1997, the year of I Love Dick and of Diana’s death, and now consumes about 15 per cent of the world’s internet bandwidth. Started by two Silicon Valley entrepreneurs, Marc Randolph and Reed Hastings, Netflix at first enabled its users to order DVDs from its website that would arrive days later in the post. When users had finished with them, they returned the DVDs in the envelopes provided. At the time, Netflix was valuable to those who had no video rental stores nearby, or couldn’t be bothered to leave their homes.

But the revolution Netflix effected on home entertainment began a few years later, when it hired Ted Sarandos and embraced what became known as predictive analytics. Sarandos had been working at a video store in a Phoenix strip mall, not dissimilar to the one where Quentin Tarantino developed his encyclopedic knowledge of cinema. What Sarandos did next, though, would make video stores obsolete. Sarandos recognized that viewers were addicts, and that his role was to supply what they wanted.

Viewers have long been battling schedulers bent on stopping them seeing what they want, when they want, he argued: “Before time shifting, they would use VCRs to collect episodes and view them whenever they wanted. And, more importantly, in whatever doses they wanted. Then DVD box sets and later DVRs made that self-dosing even more sophisticated.”

In the post-modern age, helped by technology, we dream of achieving 24/7 joy. But behind the joy are the algorithms.

But “self-dosing” makes it sound as though viewers were in control. In the same year as Sarandos was hired, Netflix introduced a personalized movie recommendation system, which used viewer ratings to predict choices for all Netflix subscribers. In 2007, it introduced a streaming service called “Watch Now,” allowing subscribers to watch TV shows and films on their personal computers. Ultimately, DVDs would become expendable: Netflix’s streaming model spread around the world not through snail mail, but through fiber-optic cables. “People have always been frustrated when they can’t get to see what they want,” Sarandos told me. “Today you can’t stop spreading the joy for long. That’s where I come in.”

Spreading the joy—a resonant phrase. In the post-modern age, helped by technology, we dream of achieving 24/7 joy. But behind the joy are the algorithms. In 2012, for instance, when Sarandos commissioned a political drama for Netflix TV called House of Cards, starring Kevin Spacey and Robin Wright, predictive analytics helped justify his decision. “It was generated by algorithm,” Sarandos told me. “I didn’t use data to make the show, but I used data to determine the potential audience to a level of accuracy very few people can do.”

Netflix’s use of predictive analytics has changed since its inception. Initially, Netflix worked on the same sort of principle as Sarandos used when he worked in a video shop. He was a human gatekeeper, designing his store’s content according to the tastes of his customer. This “if you liked that, then you’ll like this” facility has become commonplace in the new millennium, tailoring cultural supply to your tastes. And yet, customized culture such as that devised at Netflix risks creating what internet activist Eli Pariser in 2010 called “filter bubbles”: each of us isolated intellectually in our own informational spheres.

Customized culture has become much more sophisticated. Today, at least 800 Netflix engineers work behind the scenes at their Silicon Valley HQ to try to predict what you might want to watch next. Tom Vanderbilt, author of You May Also Like: Taste in an Age of Endless Choice, discovered that when Netflix was a DVD-by-mail company, customized recommendations were based on the ratings of users for particular content; but the ratings of viewers, and the predictions based on those ratings, were insufficiently accurate when Netflix went digital.

The problem for Netflix engineers is to monitor behavior less explicit than viewer ratings. In the old days of DVD rental, you added a movie to your queue because you wanted to watch it a few days later; there was a cost in your decision, and a delayed reward. “With instant streaming, you start playing something, you don’t like it, you just switch. Users don’t really perceive the benefit of giving explicit feedback, so they invest less effort,” says Netflix engineering director Xavier Amatriain.

As a result, to model tastes, more sophisticated algorithms are needed—algorithms that make Netflix sound more Orwellian than Huxleyan: “We know what you played, searched for, or rated, as well as the time, date, and device,” said Amatriain:

We even track user interactions such as browsing or scrolling behaviour. Most of our algorithms are based on the assumption that similar viewing patterns represent similar user tastes. We can use the behaviour of similar users to infer your preferences . . . We have been working for some time on introducing context into recommendations. We have data that suggests there is different viewing behaviour depending on the day of the week, the time of day, the device, and sometimes even the location. But implementing contextual recommendations has practical challenges that we are currently working on.

This observational data is more accurate than self-reported ratings: “A lot of people tell us they often watch foreign movies or documentaries. But in practice, that doesn’t happen very much.”

By this means, Netflix was delivering in reality what Wallace had imagined in fiction. He imagined the Interlace as an enormous gatekeeper deciding what you would watch while seeming to offer viewers choice. He supposed the internet would evolve similarly. Because the information supply is in principle infinite, we demand some kind of digital gatekeeper to protect us from being overwhelmed. Wallace told an interviewer: “If you go back to Hobbes, and why we ended up begging, why do people in a state of nature end up begging for a ruler who has the power of life and death over them? We absolutely have to give our power away. The Internet is going to be exactly the same way . . . We’re going to beg for it. We are literally gonna pay for it.” What dies as a result is the utopian idea that the internet or digital culture in general is democratic.

What we’re literally paying for is what Ted Sarandos calls the joy, the pleasurable experience of not deferring our pleasures. In that sense, Raymond Williams’s notion of flow—a term coined for an age before post-modernism—is not obsolete. What Netflix’s notorious binge culture results in is flow by another means, more efficient and more insidious— insidious in that we seem to be getting what we want all the time, and we suppose we have liberated ourselves from the gatekeeper of TV (schedulers), only to be ruled by another, much more sophisticated group of gatekeepers, whose task is to keep us watching while at the same time suggesting that viewers are being liberated by being given more choice.

Wallace wrote about television at a pivotal moment. In 1997, broadcast TV was not yet supplanted by streaming services, nor were the internet or social media the great sucking maws of time and attention they have since become. But at least he was not snootily deriding the medium from the outside. He called himself a TV addict, watching television pretty much indiscriminately as “an easy way to fill in the emptiness.” As a recovering drug addict, he knew something about addiction and how dealers profit from grooming users. In “E Unibus Pluram,” he analyzed how TV ensnared its viewers and emptied their pockets. Most TV criticism, he argued, indicted the medium for lacking any meaningful connection with the world outside it.

There was a generation gap between TV viewers. Those who started watching television before about 1970 watched it very differently from those who came to it later. You could call the former TV viewers modern and the latter post-modern. Those who started watching TV in the 1960s were trained to look where TV pointed, Wallace argued—“usually at versions of ‘real life’ made prettier, sweeter, livelier by succumbing to some product or temptation.” But no longer: “Today’s mega-Audience is way better trained, and TV has discarded what is not needed. A dog, if you point at something, will look only at your finger.” Post-modern viewers, in this sense, were like dogs.

Around 1970, TV became self-reflexive; it did not need real life to justify its existence. Something similar happened to literature. Realistic fiction was ostensibly about what it portrayed; post-modern meta-fiction turned from the world and withdrew into itself, drawing attention to the conditions of its construction in ironic and absurdist ways, often by playfully engaging with mass culture and the society of the spectacle. This change in literature, and its poisonous consequences for how we live, troubled Wallace when he wrote “E Unibus Pluram.”

He cited Don DeLillo’s 1985 novel White Noise, in which there’s a fabulously absurd passage involving a pop-culture scholar called Murray and his friend Jack. On their way to visit a tourist attraction, they drive past signs directing them to the most photographed barn in America, walk up a cow path past a kiosk selling postcards of the barn, and finally join tourists taking photographs of the barn. “Can you feel it, Jack?” Murray asks. “An accumulation of nameless energies . . . Being here is a kind of spiritual surrender . . . We’ve agreed to be part of a collective perception. This literally colours our vision. A religious experience in a way . . . They are taking pictures of taking pictures.”

What fascinated Wallace about this passage was not so much the parodic regress—the tourists watching the barn, Murray watching the tourists, Jack watching Murray, us watching Jack watching Murray watching the tourists watching the barn—but Murray’s assumption of the role of scientific critic at a remove from the culture of gawping. Wallace’s sense was that we’re all gawpers now, lens-dangling barn-watchers as much as pop-cultural theorists. The most absurd aspect of this parodic regress is the person who thinks he can stand outside it, observing with ironic detachment.

_____________________________________________________________

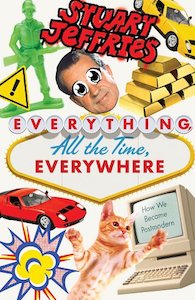

Excerpt from Everything: All the Time, Everywhere: How We Became Postmodern by Stuart Jeffries, published by Verso Books. Copyright © 2021 by Stuart Jeffries.

Stuart Jeffries

Stuart Jeffries is a journalist and author. He was for many years on the staff of the Guardian, working as subeditor, TV critic, Friday Review editor and Paris correspondent. He now works as a freelance writer, mostly for the Guardian, Spectator, Financial Times and the London Review of Books. He is the author of Mrs. Slocombe’s Pussy, Grand Hotel Abyss, and Everything, All the Time, Everywhere.