How Contemporary Chinese Literature Made Western Modernism Its Own

Yan Lianke on the Concept of “Mythorealism”

A Simple Explanation of Mythorealism

I am certainly violating a crucial taboo when I say I believe contemporary Chinese literature already contains a body of writing that diverges from both 19th-century realism and 20th-century modernism. Or, at the very least, we can say that the sprouts of this new writing have already begun to emerge—though due to the laziness of critics who don’t have the patience to perform a careful analysis, these sprouts often end up getting overlooked. This overlooked literature is precisely what I am calling mythorealism.

In simple terms, it can be said that mythorealism is a creative process that rejects the superficial logical relations that exist in real life to explore a kind of invisible and “nonexistent” truth—a truth that is obscured by truth itself. Mythorealism is distinct from conventional realism, and its relationship to reality is not driven by direct causality but instead involves a person’s soul and spirit (which is to say, the connection between a person and the real relationship between spirit and interior objects) and an author’s conjectures grounded in a real foundation.

Mythorealism is not a bridge offering direct access to truth and reality, and instead it relies on imaginings, allegories, myths, legends, dreamscapes, and magical transformations that grow out of the soil of daily life and social reality.

Mythorealism does not definitely reject reality; it attempts to create reality and surpass realism.

Mythorealism draws on 20th-century modernism, even as it simultaneously seeks to position itself outside of 20th-century literature’s various “isms” to root itself in the soil of our own national culture. The difference between mythorealism and other modes of writing lies in the fact that mythorealism pursues inner truth and relies on inner causality to reach the interior of people and society—and in this way it attempts to write truth and create truth.

Mythorealism’s distinctiveness, accordingly, lies in its ability to create truth.

Mythorealism’s Creation of Reality’s Soil and Contradictions

From the perspective of reality, literature is merely an accessory—with the type of reality determining the type of literature. From the perspective of literature itself, however, reality is the source material, and after life has been transformed into literature, it is no longer life but rather becomes literature. Writing life simply as life would be like a factory that transforms raw materials into precisely the same raw materials. It would be like taking firewood from a field and arranging it into neat piles a warehouse—but in the end, these new piles of firewood would still just be firewood.

When firewood is ignited inside an author’s heart, however, its energy may be converted into a new extraordinary object: literature. Life is comparable to those piles of firewood—and while some people may see in life the seasons, years, and the passing of time, others may see household affairs and the troubles of life, others may see poetry and the universe, while others may see only disorder and boredom. The reality of contemporary China has reached the point where it does not consist simply of piles of firewood, crops, or building tiles, but rather it possesses unprecedented complexity, absurdity, and richness.

It can be said that mythorealism is a creative process that rejects the superficial logical relations that exist in real life to explore a kind of invisible and “nonexistent” truth.

From the perspective of literature, contemporary China’s reality is a vast mud hole containing both gold and mercury, and while some authors may discover glittering gold in the mud hole, others will find that the liquid emerging from their pens is but toxic mercury. We could use the saying public morality is not what it used to be to describe contemporary China and its people, because it is impossible to understand the real circumstances of people today. Phrases like moral degeneracy, confused values, and having reached the baseline for being human are all lamentations about contemporary guidelines for society and people, and they simply demonstrate literature’s inability to control society and the precarity of our own outmoded attitudes toward literature. These phrases don’t, however, offer a fresher and deeper understanding of society and its people.

Everyone knows that contemporary China’s richness, complexity, strangeness, and absurdity vastly exceed that of its contemporary literature, and while everyone complains that we don’t have any great authors and literary works that could do justice to our contemporary era, this ignores the fact that for a long time our literature has sought merely to describe reality rather than to actively explore it.

In contemporary literature realism is understood to be a sketch of life, and it is assumed that an author’s talent lies simply in selecting appropriate pigments for those sketches. Works that describe reality are celebrated, while those that attempt to explore it are criticized. Because our realism sees its role as simply to describe reality, praise people and society, and exalt beauty and warmth, we therefore rarely find works that dare to truly to question people and society. We lament the fact that we don’t have works like Tolstoy’s that describe great social transformations, even as we lionize those works that simply describe social reality. Similarly, we complain that we don’t have works like Dostoevsky’s that interrogate the soul, even as we sing the praises of works that have absolutely nothing to do with the human soul.

When contemporary authors approach the deep truth of people’s relationship to China, they must confront three realities. First, they must confront how, in our realist writing, constructed truth is separate from—but simultaneously controls—deep truth. Second, they must confront how worldly truth classics use a combination of temptation and persuasion to approach vital and spiritual depth truth. In contrast to constructed truth’s efforts to actively undermine authors’ will to write, this latter approach is gentler but also more pernicious, because it is more capable of taking away the ideals and ideas with which authors seek deep truth. Third, they must confront the unique reality and writing environment of our simultaneously open and closed society.

In our contemporary writing environment every author must confront a combination of postReform monetary temptations, entrapments of privilege, and ideological constraints, thereby helping ensure that contemporary Chinese literature will be unable—or at least unwilling— to proceed in the direction of realist deep truth. These new ideological constraints are not simply a product of the Reform and Opening Up campaign. On the path to the vital truth, these constraints far exceed constructed truth’s attitudes of being “not permitted,” “not able,” and “not allowed,” and instead they are a result of the combined influence of politics and finance on contemporary authors’ instinctive and unconscious sense of being “not willing.” These new constraints make contemporary authors willing to abandon their pursuit of some kind of truth, as a result of which they don’t aspire to the innermost level of social reality or humanity’s inner heart.

Mythorealism does not definitely reject reality; it attempts to create reality and surpass realism.

Over time, authors will find that their inner heart—whether they acknowledge it or not—develops a barrier between their self and deep reality, and they will instinctively cultivate a habit of self regulation and self censorship when they write. There is the rich and complex social reality and the world of the human heart, but there are also barriers preventing authors from attaining this rich and complex society, together with instinctive constraints on the authors’ own writing. I believe that all authors inevitably write under these constraints, and that they understand that in contemporary literature’s process of literary composition, modernism’s attempts to describe reality cannot attain the depth or breadth of realism for which they yearn. Realism stops at a partial understanding of the world and is unable to uncover realities featuring more absurd and bizarre elements, even as authors’ struggles to break through these constraints have already become contemporary literature’s greatest source of anxiety and exhaustion.

For instance, Yu Hua has observed that in writing Brothers he was describing our country’s pain, which demonstrates his understanding of and dissatisfaction with contemporary realist literary composition, together with his embrace of “new realism.” However, in their response to this novel, many readers and critics remained grounded in an older realism, as evidenced in the way that portions of the novel that exceed the truth and logic of real life became the primary objects of readers’ contempt, controversy, and mockery. For instance, the “toilet peeping” description in Part I of the novel and the “hymen competition” sequence in Part II made almost all readers and critics laugh uproariously and spit in contempt.

If we were to summarize the critics’ assessment in one word, it would be “dirty,” though if we were to assess other literary works by a similar metric, we would have to concede that classics like On the Road, Tropic of Cancer, Lolita, Lady Chatterley’s Lover, and Gravity’s Rainbow are not particularly clean either.

Mythorealism draws on 20th-century modernism, even as it simultaneously seeks to position itself outside of 20th-century literature’s various “isms”

The root of the controversy over Yu Hua’s Brothers is not an aesthetic question of whether the work is clean or dirty but rather the fact that some of the novel’s plotlines exceed many readers’ understanding of realist writing. The novel itself does not truly attempt to surpass realism. If we look to the work for some kind of truth corresponding to real life, we discover that the toilet peeping and hymen competition sections surpass a certain truth and logic that people associate with real life, and therefore it is perhaps not surprising that the work was the object of considerable controversy and critique.

Similarly, the self-castration scene in Jia Pingwa’s Qin Opera and the floating heads scene in Su Tong’s The Boat to Redemption make readers feel as though grains of “suprarealist” or “nonrealist” sand had gotten embedded in their realist eyes. However, if we read these sections from a different perspective—which is to say, if we observe realist literature through the lens of mythorealism—these sections that surpass the old rules of realism instead come to acquire a certain kind of “mythorealist” significance, making them a prototype of mythorealism.

Today, real life is replete with pornographic culture and erotic reality, and while the hymen competition scene in Brothers might not necessarily be the best literary performance, it does offer a good mythorealistic reflection on reality, thereby rendering the scene an attempt to pursue mythorealism within the context of a realist novel. The hymen competition surpasses conventional reality and approaches “mythoreality”—thereby attaining a truth that is obscured by truth, but which nevertheless contains a conjectural and invisible truth. If we approach these controversial plots from the perspective of mythorealism, accordingly, we discover that the floating heads, toiletpeeping, selfcastration, and hymen competition scenes enrich these otherwise realistic works, marking a path toward the complex and absurdist new realism to which contemporary Chinese literary realism aspires.

The key question, however, is whether the act of introducing mythorealist elements into realist works is like mixing water with milk, or like mixing water with oil. Why is it that when this mythorealist “new truth” is introduced into a realist work, it is invariably accompanied by a strong sensory stimulation and physiological response? This is probably a trap into which contemporary literature is liable to fall when a work’s mythorealist elements exceed the rules of realism.

For instance, García Márquez describes how, in One Hundred Years of Solitude, whenever Aureliano Segundo has sex with his mistress, Petra Cotes, all the animals on his farm would suddenly become remarkably fecund. In this semi causal novel, this scene functions as a kind of miraculous reality, but if a similar scene had appeared in a fundamentally realist work it would have been criticized as an obtrusive and gimmicky oddity.

Meanwhile, Brothers is not, strictly speaking, a mythorealist work. Yu Hua himself is more inclined to view it as a realist novel, and it is true that the work belongs to a version of realism. However, I cite the novel here simply to illustrate how, when an author attempts to master the unprecedented absurdist reality of contemporary China, he will sense the contradictions between the relatively closed nature of contemporary realism and the almost unlimited openness of real life. This kind of contradiction between reality and literary creation makes an author feel confused, exhausted, and unable to proceed.

For the past three decades, contemporary Chinese literature’s repeated attempts to borrow techniques and characteristics from various different branches of Western literary modernism demonstrate that sometimes Western literary trends and local Chinese experiences don’t necessarily accord with one another. This, in turn, makes us realize that the birth of any new literary trend cannot escape the reality and the nativist cultural soil of the corresponding era. Perhaps the emergence of mythorealism in contemporary Chinese literature was spawned precisely by the contradictions that exist between the unprecedented richness, complexity, and absurdity of contemporary Chinese reality and the longstanding conventions of realism.

___________________________________

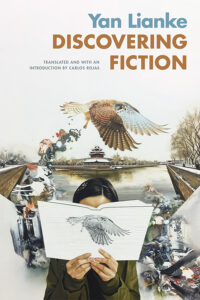

Excerpted from Discovering Fiction by Yan Lianke, translated by Carlos Rojas. Copyright © Yan Lianke, 2021. English translation copyright © Duke University Press, 2022. Available from Duke University Press.

Yan Lianke and Carlos Rojas

Yan Lianke is the author of Hard Like Water, The Day the Sun Died, The Explosion Chronicles, The Four Books, and many other novels and story collections. Winner of the Franz Kafka Prize and a two-time finalist for the Man Booker International Prize, Yan teaches at Renmin University in Beijing and the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology.

Carlos Rojas is Professor of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies at Duke University. He has translated several of Yan’s novels, including Hard Like Water, The Day the Sun Died, and The Explosion Chronicles.