How Come We Don't Have a Philosophy of Wigs?

Luigi Amara on the Curious Place of Hair Pieces in the Age of Enlightenment

Translated by Christina MacSweeney

Just one step from waste matter, the lowest of the low, an embodiment of falsehood and vanity, the wig has never belonged in the sphere of thought. As with clothing and other trivialities—daily life, for instance—anything branded as banal is of no concern to the philosopher, or not at least to the philosopher who develops his ideas in the vast empire of the footnote on a passage from Plato, the coordinates of which are fixed by immutability and permanence. An absurdity in comparison with the problem of Being, contingent and insignificant in the face of need, doubly contemptible for its seductive dimension and perceptible impurity, hair has no place in the hierarchy of illustrious topics, and much less the wig, which, as a simulacrum, fluttering in the wind far removed from the duty of imitation, would almost seem to flaunt its unreality.

But there was a time when those philosophers intolerant of all things hirsute, those minds resistant to the smaller things in life that are contaminated by non-being, sheltered under exuberant, well-groomed wigs; two long centuries during which the elevated discourse of philosophy, staunch expurgator of the trivial, found the ritual of donning another’s hair essential. Why did none of those male philosophers give a second thought to the perturbing organic mass that crowned their heads each morning? Had the infamy of existence and the degradation of the ordinary reached such extremes as to leave no room for questions about that hairy architecture, about that mammalian headwear that gazed back at them from the mirror on a daily basis?

If a meeting of philosophers had been organized in classical antiquity, the most celebrated of them—beginning with Socrates and Diogenes—would have proudly exhibited a smooth forehead, brilliant in every sense of the word. Despite the fact that Plato was only able to display a latent receding hairline, and that Aristotle, Epicurus, Heraclitus and Parmenides all had quite flourishing tresses, in the archetypal image the Greek thinker is bald as a coot with a thick compensatory beard, but devoid of the impetuosity of youth. That is the picture that Synesius, “the most valiant of bald men,” records and transmits in his In Praise of Baldness, in part to do justice to his own devastated scalp, but also to stress that hair—that animal accident, that unpredictable, superfluous attribute—has nothing in common with the heights of abstraction. If his humorous text is to be believed, the majority of classical philosophers lived in that state of asymmetry, that tension between “barren pate” and “populated understanding.”

But if a collection of the busts of Greek philosophers could be mistaken for a museum of androgenic alopecia in which the marble itself contributes to the mirage of a melancholy exhibition of full moons, in the modern era—less given to statuary—an assembly of that nature would include samples of wigs. Descartes, Locke, Leibniz, Berkeley, Rousseau, Hume, Kant . . . all have a place reserved in the grand album of the hairpiece, and although the philosopher himself might brand it as frivolous, strictly excluded from higher authority, it is worth considering the consequences of the fact that modern philosophy, incapable of applying Occam’s razor to its own excrescences, to its unquestioned habits, achieves its fulfilment in the shelter of some form of hairy bonnet.

Just one step from waste matter, the lowest of the low, an embodiment of falsehood and vanity, the wig has never belonged in the sphere of thought.

Descartes, who thought wigs were beneficial to health, had at least four in the color of his actual hair; it is uncertain if this was because they allowed him to pass unnoticed and so continue the unsociable and solitary lifestyle he preferred, or if he collected them because they were formidable confirmation that everything related to the body and appearance is volatile, secondary, non-essential. Kant’s wig, in contrast, was white, stiffer and more codified, and while, to judge by James Boswell’s description of their meeting, it was so ill-fitting that his servant was constantly employed in straightening it, he was never without it, as if the hairpiece were the literal condition of the possibility of his experience, the necessary frame—a sort of hirsute a priori—of his public and professional lives.

Workshop of Klose and Wollmerstädt, Kant and Friends at the Table, 1892–3, colored wood engraving after the Emil Doerstling Rococo painting, which could also be called After-dinner Wigged Conversation.

Workshop of Klose and Wollmerstädt, Kant and Friends at the Table, 1892–3, colored wood engraving after the Emil Doerstling Rococo painting, which could also be called After-dinner Wigged Conversation.

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the use of the wig was so widespread that not even such an enemy of superfluous adornment as Jean-Jacques Rousseau would have had the courage to spurn it. Having resolved to restrict himself to a diet of independence and austerity that eschewed any form of sophistication and luxury, rather than wholly dispense with his wig, the defender of the noble savage and the return to nature exchanged it for a simpler model. Was it still a mark of distinction even for those who constantly insisted on the equality of all men?

Was the hairpiece, perched upon the social body, so ubiquitous that it became invisible, even to the champions of sapere aude, the proponents of independent thought and Enlightenment? Could it be that the very genealogy of importance they contributed to tracing—that definition of what could be considered to fall within the realm of philosophy, that reality stratified by rank—made them incapable of reflecting on that age-old custom, so it never even crossed their minds that the wig was in fact a figure of ostentation and excess, pomp and appearance, the outrageous trophy of its visibility? Could it be that the wig in some way thought in them—through them—like a reflection of that unnoticed but standardizing and disciplinary weight with which society and its symbolic practices structure and give form not only to thought but to the body?

Such questions were never even posed. The philosophers might groom their wigs each night and ensure that they were made by the best coiffeurs in Paris, but although they were only separated by the thin wall of the cranium, thought and the wig never met. With the possible exception of Leibniz, who, in the spirit of the Baroque, elaborated a philosophy of facade and, by extension, of the wig (of the need for a division between independent, monadic thought and that other sphere which offers itself to society and deals with its conventions and obligations), their concerns moved in the opposite direction from what was nesting on their heads. If philosophy could no longer turn its back on the world of appearance without suffering the consequences, it did not seem prepared for the scandal of the simulacrum, that discordant third party that does not aspire to being a copy of anything, that subverts the opposition between the model and the copy, and, with the bare-faced cheek of its artifice, simply intends to produce an effect.

Was the hairpiece, perched upon the social body, so ubiquitous that it became invisible, even to the champions of sapere aude, the proponents of independent thought and Enlightenment?

With their attachment to the trifling, those who address such superfluous issues as hair do not belong in the lineage of philosophy—although they perhaps find a place in literature or open provocation. The mere questioning of which themes merit elucidation is an act of dissidence, a step outside hegemonic tradition; due to the non-conformity of the gesture, the eccentricity of the quest, the person who does question must be willing to bear disdainful references: a juggler of insignificant trifles, a hunter of trivialities, a clown of thought. After adding a touch of humor and irreverence to Platonic dialogue (to stop it walking on air, as he explained), Lucian of Samosata, author of The Fly, an Appreciation, was accused of philosophical high treason, while Dion of Prusa, who wrote Encomium on Hair, was, after Philostratus, pigeonholed as some form of sophist since it is in the manner of sophists “to take these matters seriously” (and it goes without saying that a philosopher has no business amusing himself with a paradoxical encomium, with the exaltation of what is low and paltry or with problems that no one would dream of sculpting in philosophical marble). Not to mention Michel de Montaigne’s officious expulsion from philosophy and his displacement into literature for having dared to “reflect so brilliantly on such insignificant topics” as thumbs, wearing clothes, smells and idleness.

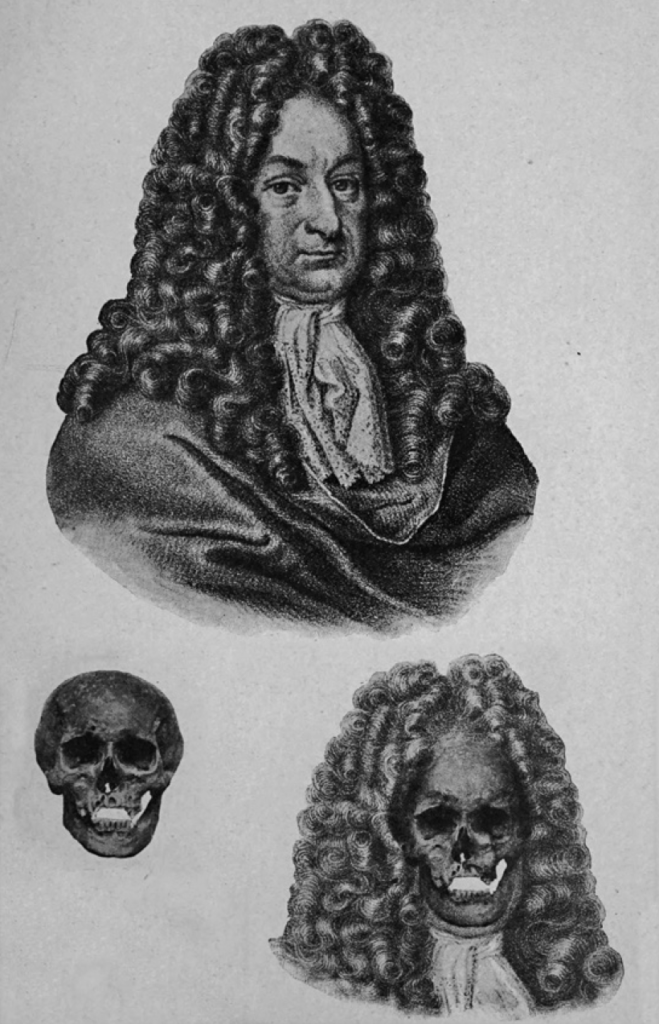

The skull of Gottfried Wilhelm von Leibniz projected onto a portrait engraving in which he is wearing his baroque wig, published in Zeitschrift für Ethnologie by W. Krause (15 November 1902) as “proof” of the authenticity of Leibniz’s remains.

The skull of Gottfried Wilhelm von Leibniz projected onto a portrait engraving in which he is wearing his baroque wig, published in Zeitschrift für Ethnologie by W. Krause (15 November 1902) as “proof” of the authenticity of Leibniz’s remains.

Amusement, fun, essays. Margins in which peck exiles from that centre philosophy recognizes as its own under the dictum of “the real is rational and rational is real.” If, after Plato, one of the tasks of philosophy had consisted of producing difference—distinguishing between the authentic and the spurious—who was going to say that right there, on the very heads of its apostles, it was necessary to set an untimely bird of ill omen that eludes the contrast between essence and appearance, the scandal of the simulacrum, the wig that no longer aspires to resemble anything “original,” that claims possession of its own imposture, its clearly false truth and, in the triumph of its lack of resemblance, its phantasmal apotheosis beyond life and death, evades the degradation of being a mere copy of a copy?

Nothing but a sophist head of hair. Hair with no other grounding principle than the impression it makes. Without roots but flaunting its foliage. Mask hair. And where else but on the crowns of the most distinguished philosophers?

__________________________________

From The Wig: A Hairbrained History by Luigi Amara, published by Reaktion Books Ltd. English-language translation copyright © Reaktion Books 2020. Translated by Christina MacSweeney. Copyright © Luigi Amara 2014. Originally published by Editorial Anagrama SA.

Luigi Amara

Luigi Amara is the author of many poetry collections, essays, and children's books, including Nu)n(ca, winner of the International Poetry Prize in Spanish, and The School of Boredom. He lives in Mexico City. Christina MacSweeney (translator) is an award-winning literary translator specializing in Latin American fiction.