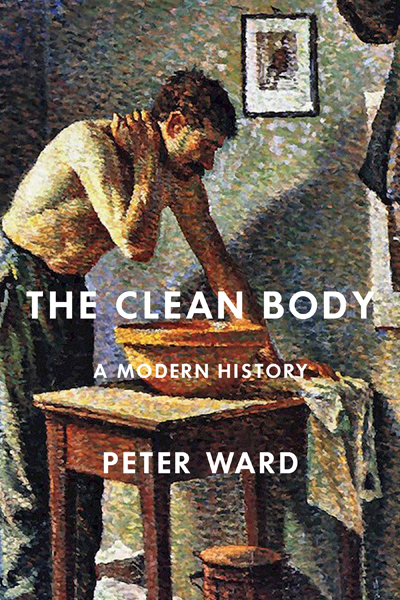

How Cleanliness and Beauty Became Intertwined

in the 18th Century

Peter Ward on the Rise of Self-Help, the Literature of

Advice, and More

A publishing tradition as old as the printed word, advice literature flourished from the later 18th century onward, spurred by the spread of literacy, the declining cost of book publishing, an expanding middle class seeking guidance on right conduct, and the increasing numbers of self-declared experts keen to profit from the market for advice.

Self-help books circulated, and at the same time reflected, a wide variety of views about appropriate behavior. Before the mid-18th century they had little to say about how to accentuate feminine beauty and preserve it from time’s certainties. Rather, they viewed a woman’s attractions in relation to her conduct, placing them in a moral sphere rather than a physical setting.

A curious novel by a Parisian doctor published in 1754, however, departed from the usual offerings of the loveliness literature. Abdeker ou l’art de conserver la beauté, by Antoine Le Camus, purported to be the translation of an Arabic manuscript from the time of Mahomet II, the Ottoman Sultan who conquered Constantinople in 1453. It was a tale of illicit love between Abdeker, a young physician to the women of the Sultan’s harem, and Fatmé, an odalisque in his seraglio and a woman of unequaled sweetness and beauty. Time and again Abdeker gained access to the darkest mysteries of the harem, to say nothing of the forbidden charms of the lovely Fatmé, by teaching her the means of preserving her beauty while instructing her in the arts of love.

Le Camus wrote in the Orientalist tradition of the erotic exotic. He was one among many Western observers of the Ottoman world fascinated by the image of the harem, with its imagined air of perfumed sensuality and sexual licence. His book was republished at least four times over the coming decades, was translated into English and Italian, and was still in circulation when Mozart’s Die Entführung aus dem Serail and Rossini’s Il Turco in Italia and L’Italiana in Algeri used the harem to comic effect. In the visual arts, Western painters—famously Ingres in his Grande Odalisque—returned time and again to the theme of the seraglio from the late 18th century onward.

The curiosity of the book, however, came neither from its romantic plot nor from its erotic overtones but from the fact that it offered feminine beauty tips on a broad range of subjects, bathing among them. Le Camus dotted his text with bits of practical wisdom about women’s health, offering handy summaries of his major points at the end of each of the book’s two parts. Here was a healthcare catechism with a difference!

His advice on bathing was set in the context of Abdekar’s visit to a bath in the harem, a luxurious setting rich with the promise of voluptuous delights. But the author’s suggestions about bathing were quite prosaic. One bathed to preserve a white skin and to cleanse it of dirt, for pleasure and politeness as well as for health. Bathing offered a host of natural benefits, Le Camus declared, yet one should proceed with caution because inconsiderate use could be the cause of major ills.

A publishing tradition as old as the printed word, advice literature flourished from the later 18th century onward.

With its emphasis on a suggestive world of exquisite sensuality, Le Camus’s advice left the idea of such a bath in the realm of his reader’s imagination. For all but the most privileged Europeans of the time, even the remote possibility of actually bathing in this manner was utterly out of reach. In this respect the author’s views on how to display and preserve feminine attractiveness were out of step with those offered by most other advisers of the later 18th century. The beauty counselors of the period had little to say about washing the body and much to say about a host of other matters: cosmetics, perfumes, hair care, and dress, to name a few.

But soon after the turn of the century, some of these self-appointed advisers—most of them male—began to pay more attention to the role of bathing in women’s personal care. One of the first was Auguste Caron, whose Toilette des dames ou Encyclopédie de la beauté, published in 1806 and later translated into English and Italian, hymned the importance of cleanliness to women’s beauty. As the English edition explained,

there is in the toilette of women one very essential requisite, and which constitutes its greatest merit in the eyes of the delicate man; I mean cleanliness. Cleanliness alone, unaccompanied by any other recommendation, has a right to please, to attract the eye, to gratify the taste, to excite desire; the toilette, without cleanliness, fails in its object; it displays only idle pretentions, bad taste and low sentiments. . . .Cleanliness is that precious quality which nearly transforms a woman into a divinity, by removing from her every thing that might betray the imperfections of human nature.

In Caron’s view, careful attention to her personal hygiene, of her body and its clothing, was the primary means a woman had to display and preserve her beauty. He advocated frequent bathing in warm water—never cold, which injured feminine loveliness—and even suggested that scented soaps might be used to cleanse the skin more perfectly. The face, hands, and feet should be washed regularly if bathing was not possible. Hair, however, was quite another matter. While Caron advised the same high standards for its cleanliness, he strongly criticized washing the head with water, which produced aches of the head, ears, and teeth, as well as eye complaints. Regular combing and the occasional application of hair powders or bran would keep it clean.

The 19th-century woman addressed by these authors could only be a lady of leisure. The frequent baths proposed by an anonymous Italian author in 1827—at least once weekly and more often in the hot season—should take at least one and a half hours, an opinion shared by Mme Celnart, another mentor generous with her advice about matters feminine. A generation later Auguste Debay, the prolific and widely published French author of guides to hygiene (clothes, diet, beards, vocal organs, marriage, hands and feet, to name only some), suggested that baths should probably last longer still. Obviously the woman imagined by these authors had time on her hands.

By the early decades of the 19th century the virtues of the bath had become indisputable, and from this point on it occupied a central place in the advice directed to women.

But of far greater significance, by the early decades of the 19th century the virtues of the bath had become indisputable, and from this point on it occupied a central place in the advice directed to women. As Debay claimed in 1846, the warm bath is essential to the cleanliness of the body, to the maintenance of its flexibility and freshness; one can consider it necessary for the general health of the individual.

Modesty and Ambivalence

But whatever support bathing could muster from the health and beauty guides, it also had to contend with misgivings and restrictions, for modesty challenged the spread of the bath throughout much of its long history. The Greco-Roman myth of the huntress Artemis (or Diana) and Actaeon was one of its early expressions, most widely known from the Renaissance onward through Ovid’s Metamorphoses. Tired from her day’s hunt, the chaste goddess Diana was surprised while bathing in a limpid forest pool, together with her attending nymphs. The male intruder was the mortal Actaeon, a hunter like herself, who blundered alone into her sacred grove at the end of his day’s pursuits. The nymphs tried, but failed, to cover Diana’s nakedness with their own and Actaeon saw her unclothed. In shame and anger she took revenge by depriving him of speech and turning him into a stag. Transformed, he took flight, but soon his hunting dogs took up the chase and, unable to cry out, he met his death at their jaws, avenging Diana’s wronged modesty.

The myth was a recurring theme in European painting from the 16th to the 18th centuries, with Titian, Rubens, and Rembrandt among the many artists drawn to various moments in the story. Some depicted Diana quietly bathing alone, others the goddess in her grotto surrounded by her attendants. Still others—notably Titian—portrayed the dramatic moment of Actaeon’s fatal glimpse and Diana is chilling response. But the thread running through them all was a sense of diffidence and reserve that surrounded the bathing female.

__________________________________

Excerpted from The Clean Body: A Modern History by Peter Ward. Copyright © Peter Ward 2019. Reprinted with permission from McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Peter Ward

Peter Ward is professor emeritus of history at the University of British Columbia and the author of several books on the social history of Canada and the history of population health.