How Christa Päffgen Became the Iconic, Mysterious Andy Warhol Superstar Known as Nico

Jennifer Otter Bickerdike on the Beginnings of the Model and Velvet Underground Singer

As an adolescent, Christa Päffgen began working on some of the attributes that would become integral to her later “Nico” persona. Helma Wolff, Christa’s aunt, pinpointed the time when the deep, baritone pronunciation, which was synonymous with the singer’s work, began. “It started about the age of 12,” she recalled. “She often came to me after school and asked me in her strange pronunciation, ‘Aunt Helma, is Ulli also there [said using elongated vowels]?’ She always sang like that.” Though “as a child she had a dark voice,” Aunt Helma still tried to get the pre-teen girl to “talk reasonably, say the words short.” Christa’s mother Grete also noticed the difference in her daughter, but simply wrote off the odd behavior as a symptom of impending puberty.

Nico later reflected on this time, stating, “When I was young in Berlin I was not interested in many boys. Well, I was interested, but nothing more. I was shy. I have always been shy, this has been my difficulty. Some people think I am distant, while I think I am shy.”

Though admittedly a bit reticent, the determined and innovative young girl set her sights on trying to connect with the local fashionable set, spending time on the most aspirational streets in Berlin. Filled with shops, fashion houses, hotels, and restaurants, the thoroughfares provided a glimpse into a tantalizing world, far away from the atrocities the young teen had seen and experienced. Christa also began haunting key shopping ports of call religiously, praying and hoping to be noticed by anyone who might be able to help her. Helma recounted, “She took walks on the Kurfürstendamm, she went window-shopping. She had no friends, she just went by herself.” Another favorite spot for the teen was Berlin’s elite shopping center, the Kaufhaus des Westens (Department Store of the West, or KaDeWe for short).

Like its upscale cousins Harrods of London and Bergdorf Goodman of New York, the KaDeWe catered to a well-heeled clientele keen to snap up the latest and greatest fashions. With her tall stature, graceful body, and high cheekbones, Christa attracted a lot of attention, with Helma remembering, “Christa was always noticed by everyone. What a proud child this is. A uniquely beautiful girl… You couldn’t miss it.”

*

Considered one of the foremost German fashion designers of the post-war period, Heinz Oestergaard catered to a wealthy clientele and celebrities. Housed within the KaDeWe was his “salon,” where his newest pieces were featured. Instead of immobile plastic dummies, Oestergaard used good-looking young women to model his creations for potential customers, yet still referred to them as “mannequins” or “dummies.” However, any job with Oestergaard was highly sought after, and his agents were constantly looking for new talent to inject into the daily fashion shows occurring within the sacred rooms. Christa caught the eye of one agent as he was planning the KaDeWe autumn show of 1953. Finally, her persistence had paid off.

Once she began, Christa soon saw that the realities of the job were less than glamourous. Mannequins were hidden behind a screen in the salon, where they quickly changed outfits, refreshed makeup, brushed out wigs and tried not to appear too sweaty as they modeled the newest styles for the attending glitterati. Nico later described the experience as “an alternative school. I understood why everything had to be just as it was; I could see the effect of a walk, a turn, a position… I was the center of attention.”

The 1995 documentary Nico: Icon, written and directed by Susanne Ofteringer, provides invaluable interviews with many of the key figures in the artist’s life. It is a subjective film, painting Nico as neither a fallen martyr nor an unredeemable mess. Instead, it is one of the only texts that presents Nico as a flawed, interesting, troubled human. Ofteringer’s first person, primary interviews with family, friends, and colleagues—many of whom have sadly now passed away—provide a fairly well-rounded narrative of the woman behind the mythology.

This is especially relevant through reflections provided by Nico’s Aunt Helma.

“She could move her body and act,” Helma remembered. Thanks to her success with Oestergaard, the opportunities began pouring in. Christa excelled, even winning the title of “best mannequin at a parade to show off new items” at one event. Her prize for the triumph was the rings she had modeled. A young photographer named Herbert Tobias was enlisted to snap her studded hands—and that, her aunt Helma recalled, “was the beginning.”

Tobias—who always went simply by his last name—was renowned for providing ornate, professional portraits for the fashion media, taking mannequins like Christa and transforming them into cover girls. The two quickly became close. Tobias proved to be both a good friend and a mentor. Fourteen years her senior, the photographer gave the teen her first color spread, for the magazine Bunte in January 1955. Though not often credited, further collaborations followed. Tobias’s images from these early modeling days reflected the teenager’s ability to transform seamlessly in front of the camera.

Nico had become so good at playing Nico that she rarely showed anyone her authentic self.

At one of the many fashion shows Christa had started doing, someone from Vogue magazine approached her mother. The offer was beyond tempting. Grete was told that Vogue could offer her daughter a fantastic, affluent career in Paris. Yet despite living hand to mouth and with the threat of violence omnipresent, it was a tough decision. “Paris was the center of the fashion world, you could not go higher. Imagine what she would earn! Imagine the fame!” recalled Helma. But Grete was not as easily convinced. “My sister said, ‘I couldn’t give my child to a completely foreign world. What’s all this about?’” Helma recounted. But the girl was obstinate. “Christa cried and said, ‘Mummy, even if you don’t want it, I’m going without you!’ Then she went directly to Paris.”

At the time, Christa was determined to provide a better life for herself and Grete. In 1969, she reflected on that first departure from Germany, telling Twen, “At 16, I became a photo model. I simply did what seemed easiest to me; after all, I had to take care of myself and my mother.” The teen wanted to pay Grete back for the unconditional love and support she had provided, and saw becoming a professional “dummy” as the easiest way to accomplish this. When later asked if she enjoyed the profession, Nico answered, “No. I have not thought long whether I enjoy it. I did it to feed ourselves.” Like it or not, Tobias had plans for his new protégée, viewing her as a vehicle for the rehabilitation of his post-war career. In Christa, Tobias recognized his own grit and determination. Having already tasted success on the Parisian fashion scene, he wanted to position the girl for similar fame. Christa was a willing and eager pupil.

Partnering with Tobias was an early example of her ability to take the initiative. One day in 1956, he prompted Christa to make a life changing decision, as her name was “all wrong” and “not international.” “Models have one name, just like photographers and designers have one name,” he told the model. She recounted how she got her new moniker, saying, “When Tobias took the first fashion photos of me, my name was Christa Päffgen. Tobias said, ‘That’s no name for a model. You’ve got to change your name. I’ll name you after a man I once loved in Paris. His name was Nico. That’s a nice name for you.’”

Christa’s new moniker allowed for an entirely different persona to be born, one without the baggage of family issues, poverty, violence, and patriarchal frameworks. As Nico is usually a name for men, suddenly even the limited opportunities and expectations for a female artist seemed temporarily non-existent. “Nico” allowed Christa to seemingly shed her past and step into an unpolluted simulacrum.

In the 1969 Twen interview, when asked about her memories of the war, Nico responded, “That was not me, that was another girl… My memory consists of shreds and short flashes, never the whole picture.” Though she thought she was at last outwitting her past, Christa never fully became Nico, remarking, “You don’t have to be you to be you.” It would remain simply a role, an “other” that she was portraying to the outside world while still eternally haunted by her youth. When asked how she dealt with the idiosyncrasies of modeling, she responded, “I was an alien… I did not take it seriously. I could laugh… because I was playing the part of Nico.”

For the rest of her life, she would maintain the dual personas: Nico, the created, cool ice queen that she showed to the world and her audience expected; and Christa, the brave yet damaged survivor at the core of her being, the tormented casualty of a grim childhood. In the over 100 interviews for this book, not one person remembered ever referring to the singer by anything else but her Tobias-chosen name. Nico had become so good at playing Nico that she rarely showed anyone her authentic self.

__________________________________

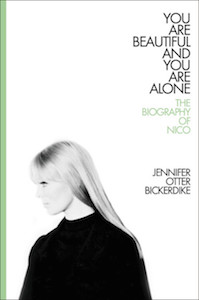

Excerpted from YOU ARE BEAUTIFUL AND YOU ARE ALONE: The Biography of Nico by Jennifer Otter Bickerdike. Copyright © 2021. Available from Hachette Books, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Jennifer Otter Bickerdike

Dr. Jennifer Otter Bickerdike is the Global Music Ambassador for BIMM, Europe’s leading & largest music college. Originally from Santa Cruz, California, she has spent her life dedicated to the mistress that is rock n roll, with more than 30 years of experience in the culture industries, ranging from her time as a former music industry executive in the US to surviving three waves of dot com bubble bursting in the Silicon Valley before writing her PhD on Joy Division and Nirvana at Goldsmiths College in London. She is also the author of WHY VINYL MATTERS, a manifesto of the importance of the vinyl record by and for fans. The book includes interviews with a wide array of aficionados, ranging from Lars Ulrich to Fatboy Slim. Bickerdike lives in London, UK with her husband and rescue dog Alfie.