How Chinese and Italian Opera Helped Her Write and Grieve

Liu Hong on Navigating Tragedy in Art and Life

Years ago in North China, I was taken, reluctantly, by my grandmother to my first opera. It was a regional performance of a revolutionary opera whose name I forget. A teenager, I was bored almost as soon as I grasped the not very inspiring plot.

My particular grind, uninspiring plot aside, was the lengthy process the hero took to die. Of course I didn’t want him to die, but once his fate was sealed, I just wanted it over and done with. But he sang aria after aria, and finally… I fell asleep.

On the way back home, my grandmother agreed that the storyline was ridiculously formulaic—there was a reason they were called Revolutionary Model Plays. “But I miss seeing live performances.” She sighed: “That’s why I had to come to this. If I close my eyes and listen only to the tunes, I can pretend it was one of the old ones….”

I was lucky that my introduction to Chinese opera was with my grandmother Tian Jingyu, the best storyteller in the world. Through her, I learned traditional stories often suppressed at the time, and of course I got to listen to a lot of operas—on my father’s gramophone record, since no traditional operas were allowed to be performed when I grew up.

We are Northerners and our regional opera are the Pingju, the most famous of which is the tragedy of Qin Xianglian, the Wronged Woman, who pursued revenge and justice on her cruel and faithless husband, Chen Shimei. Not content with abandoning Qin when he caught the eyes of the emperor’s daughter, Chen also schemed to have her and their children murdered.

Xiao Baiyushuang, who sang the part of Qin Xianglian, moved millions to tears with her rich contralto voice, my grandmother told me, as she hummed her favorite piece from the opera—the one when Qin Xianglian stood in front of the princess and argued, with eloquence, righteousness and dignity, why the princess should get off her golden palanquin and bow before her, the pauper first wife. Even as a child, I found the mellow, melancholic tune deeply affecting.

As my knowledge of opera grew, so did my taste for more. I fell in love with another Pingju classic: Hua Weimei, Flowers as pledges of our love, a comedy of errors about two couples finding happiness through a series of misunderstandings. In contrast to the tragic lament of Qin Xianglian, this was a story full of witty banter rendered in gutsy northern accent by lively, vivacious women. The humor of the latter moved just as much as the pathos of the former.

In time I also discovered Peking opera, and the work of Mei Lanfang, that beguiling male super star who sang all the best feminine parts: The Fairy who spreads blossoms all over Heaven, Daiyu who laments the brevity of beauty; Empress Yang who drunkenly seduces the emperor… I learned by now how traditional operas used to be performed and appreciated: in busy, bustling marketplaces as well as grand mansions, through many a noisy banquets and loud cheers.

A world away, then, from my first introduction to Western opera.

La Traviata at the Royal Opera House, with my English father-in-law. My sense of awe was not just for the performance, but also the richness of the theatre’s interior and the deep silence once the first note of the opera was struck.

So began an expensive pastime. I saw La Boheme numerous times, and fell head over heels for Puccini, to my husband’s consternation—a Mozart devotee, Jon found Puccini far too sentimental.

These were world class performances in one of the most beautiful theatres in Europe, and for a long time, I held the firm belief that opera best experienced in reverent silence.

For our thirtieth wedding anniversary, we headed for Verona. During the day, we gorged on gelatos and basilicas; at nightfall, inside the vast, iconic Arena, under glorious Italian sky, we feasted on Carmen, Aida, Turandot… and adhered strictly to the rules of no food and no sound.

But night after night, the Italian family sitting next to us chatted and picnicked and were always ready to cheer—they were not reprimanded by anyone. By the third night, we, too, brought in food and drinks, chatted and cheered. We had a most wonderful time. My grandmother would have approved.

Both Italian and Chinese operas were deeply rooted in rich, traditional culture, both boasting of wide appeal transcending class and other barriers. As a writer, I found opera stories endlessly fascinating. My novels were all set in China, and I wrote in English.

Italian operas became, for me, the perfect background music. I didn’t know Italian, so the words could not distract me. But when I wrote, I was in a trance, transported to another world in which the opera music gave a true sense of drama and of story unfolding, setting a reassuring rhythm and undertone. They brought me back to the writing when my mind wandered and inspired me when the creative juice ran dry.

Then, taking a break from writing, I would play A Pingju or Peking opera to relax and be reassured in my mother tongue.

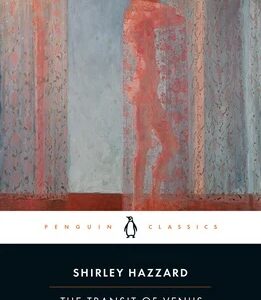

I played Puccini incessantly, almost by instinct, while I wrote my latest novel, The Good Women of Fudi—a historical fiction, an unrequited love story between two Chinese women and a romance between a Chinese feminist and a Western man. La Boheme, Madama Butterfly, and Turandot became set pieces.

Opera best reflects the universal chaotic nature of life; it is the perfect medium for big emotions. My novel contained many love scenes and as a result, I became familiar with some sublime duets: Alfredo and Violetta’s duet “Un dì, felice, eterea” in Verdi’s La traviata, “O soave fanciulla” between Rodolfo and Mimi in La Boheme, Butterfly and Pinkerton’s “Vogliatemi bene” in Madama Butterfly….

Even as I believed listening to them inspired my writing, I did wonder sometimes if the intoxication of being in love could ever be as fully expressed in mere words– music seemed much better suited to love’s ecstatic nature. But writing is my vocation, so I kept on chipping at my statue made of words –my “castle in the air” as Rodolfo has sung.

Grief, too, fitted opera like a glove. I get now—as a grown-up—the lengthy time it took for heroes/heroines to die, for our all-consuming emotion demands it. Grief is something you cannot rush. Charles, my Edwardian character grieving for his dead wife, found solace and comfort at a live show of a Chinese opera performed in the open air on a make-shift stage underneath a banyan tree in a Southern Chinese treaty port.

When I wrote about Charles’ grief I had used that oldest trick of the trade—imagination. Little did I know then how soon life would imitate fiction. Just over a year ago, a month or so after I had learnt that the Good Women of Fudi was to be published, on a beautiful May day, I lost my husband of thirty-three years.

In time, I realized that though those familiar tunes of happier times brought tears, they were preferable to the silent crying inside.A fellow writer, Jon and I both used to play music as we wrote. Surrounded by books, maps and manuscripts, Jon would spread out in our downstairs sitting room with Bach, Mozart and the occasional blast out of punk rock while he penned exaltation on his favorite English Parish churches and cathedrals—his enduring love. When I came down to make my cup of tea, he would turn his music down and apologize to me—only half-heartedly—for its loudness.

For a long time after his passing, I could not bear to listen to any music, especially opera, and the house was a silent tomb. It felt safe that way. Grief robbed life of meaning. I existed, that was all. Writing became the last thing I wanted to do. What was the point? I could not conjure up another world, for the pain of this one was only too real.

But I could not help catching snippets of music here and there, even though I still couldn’t bear to play any myself. In time, I realized that though those familiar tunes of happier times brought tears, they were preferable to the silent crying inside. Grief is the price we pay for having loved, it has been said; it is part of being human.

The children, too, showed me how to live with grief. Our eldest daughter composed beautiful, furious songs; our youngest took to going on long cycle rides to the path she used to go with her father; our middle daughter begged to be taken to an opera.

We went for La Boheme, her first. It felt good to cry together.

*

Remembering Liu Hong’s late husband, Jon Cannon:

Jon Cannon (1962–2023) is the author of Cathedral: The Great English Cathedrals and the World that Made Them (Constable, 2007), and The Secret Language of Sacred Places (Duncan Bird Publishing, 2013). Jon presented How to Build a Cathedral on the television channel BBC4 (2008). Jon’s latest book, The Stones of Britain, will be published in April 2025 by Constable.

______________________________

The Good Women of Fudi by Liu Hong is available via Scribe.