How Centuries-Old Knowledge of the Natural World Can Save Lives

Simon Winchester on the Uses and Evolution of Ways of Knowing

It is surely true that for all sentient beings life itself is the most precious of commodities, to be preserved at all costs. Anything that threatens existence—any danger, any potential assault, any whiff of menace—is to be avoided, and of all the kinds of empirical knowledge of which the being becomes aware, that of impending danger is pre- eminent. The knowledge—gained usually from experience—that fire is a danger, that ice can freeze the life away, that water can drown, that a wasp can sting and cause great pain—all such matters are apprehended early on in life, by animals and humans alike, in order to help preserve the species.

And in more than a few ancient indigenous cultures throughout the world, such basic, near-instinctual knowledge lies at the very core of their collective being, and on occasion results in a communal response that inspires awe and envy from supposedly more advanced, more sophisticated onlookers.

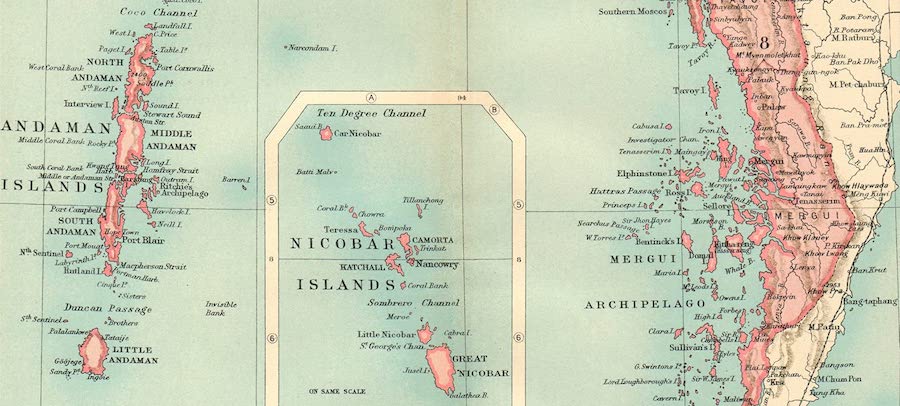

A case in point, which offers one of the more vivid recent examples of indigenous knowledge at work in recent times, came about on the Andaman Islands, the string of limestone jungle-covered skerries lying in the Bay of Bengal, off the coast of Burma. The islands, tropical and until recently seldom visited by outsiders, are officially Indian sovereign territory, and are populated mainly by Bengalis and Tamils from the Indian mainland—a total of some 350,000 people, most of them farmers and foresters.

But there are also a scant few hundred aboriginal people on the archipelago too—tribes known as the Onge, the Jarawa, and the Sentinelese. Their unique possession of traditional knowledge of their natural environment by all accounts saved their lives. All of them.

Sunday, December 26, 2004, is memorialized across the Indian Ocean as the date of an enormous undersea earthquake and a consequent unimaginably lethal tsunami. The enormous drowning wave headed at immense speed from its epicenter at the northern tip of the Indonesian island of Sumatra and spread unstoppably through the Bay of Bengal, devastating coastal communities—and tourist destinations—in Thailand, India, Sri Lanka, and beyond. Some 230,000 people died, in the worst natural disaster of the century thus far.

The value of their knowledges is underlined by the immense care taken to guard and then transmit them.

The waves struck the Andaman Islands in the midmorning, roaring up the island chain at some 500 miles an hour, thrashing uncontrollably up the beaches and dragging to their deaths as many as seven thousand people. Almost all of the victims were Hindus, descendants of mainland Indians who had come to the Andamans many years before. But of the five hundred indigenous inhabitants, those belonging to the aforesaid Onge, Jarawa, and Sentinelese groups—all of whom have great hostility to newcomers and have long made clear their wish to be left alone—not a single one died in the tragedy. All escaped the ferocity of the inrushing waves—because, quite simply, they knew what to do.

There is still some uncertainty about how they knew. Songs, say some students of the groups. Long-remembered poems, say others. The saying of the tribal elders, shouted down to the youngsters. But whatever the mechanisms, what occurred appears to have been common to all of them. Those on the beach, fishing or mending nets, suddenly noticed a series of unusual changes in their surroundings: the swift out-running of the tide, the unexpected drying of the sand, the changed color of the seawater, the line of spume and spray on the ocean’s far horizon.

They had no immediate idea of what this might presage—just, for all of them, a distant memory, a few snatches of poetry, or song, or utterances from village shamans or elders—memories that hinted a vaguely recalled instruction: that when such things happen you need to run, and run inland and up into the hills and run deep into the forests. Run uphill, up, up, up!

So they did as memory bade them, and they gathered up all the slowpokes and the otherwise occupied and took themselves by the hundreds up into the hillside darkness from where they watched, horrified. The huge waves began to swallow up the beach where they had been just a few moments before, wrecking houses, upending and sinking boats, picking up and drowning dozens of villagers—Hindu villagers, mainlanders, outsiders, migrants—who had no inkling of what to do.

Maybe they watched in horror, maybe they were terrified, but they lived, all of them. And they survived because they had the knowledge, knowledge that had been handed down to them through generations past. They were in possession, unwittingly no doubt, of what some like to call, fancifully, “the original instructions.”

Indigenous peoples around the world have similar wellsprings of ancient knowledge, most of it employed for more ordinary matters than a terrible emergency. So varied are these areas of traditional awareness that anthropologists prefer to employ the plural form, knowledges—although there is much argument today about whether distinguishing between traditional knowledges and the vast range of topics known to those later settlers who displaced the original inhabitants is condescending in itself, an extension of old imperial habits toward those who were once thought of as primitive or childlike or savage.

Inevitably, once the plural term became commonplace, debate began about what one might call the relative qualities of these knowledges, the relative value and worth of one kind of knowledge compared with another. Is the knowledge of particle physics by a German scientist of greater value than a Canadian Inuit’s knowledge of different kinds of snow? Does giving the different species of tigers impressive names in Latin render them significantly better known than the ways in which Siberian forest people tell one big cat from another? Are the star charts used by nomadic peoples in western China and Tibet inferior to the complex atlases of the cosmos published by the sophisticated national space agencies? Such questions oblige one to tread gently, to regard all knowledge as somehow sacred, of as much worth to people as the people themselves consider it to be.

The very earliest means of transmitting knowledge, those that still involve surviving indigenous peoples, have certainly endured. They are primarily oral or pictorial in nature: they tend to involve stories, poetry, performance, rock carving, cave painting, songs, dances, games, designs, rituals, ceremonies, architectural practices, and what the aboriginal peoples of Australia know in their various languages* as “songlines,” all passed down through the generations by designated elders or specially skilled custodians of each form of cultural expression.

Although settler colonists regarded these expressions as merely amusing, charmingly primitive, and attractive to travelers seeking folklorique performances, they have lasted very much longer than many of the equivalent and ever evolving methods of the arrivistes. The Internet has upended everything, of course, as did the creation of radio and television and the electronic networks based on their technologies. But in so many instances, the temporary ruled. Morse code, for instance, was useful for rather less than a century. The telex for a couple of decades. Fax machines whirred and wheezed annoyingly for a laughably short time, maybe twenty years.

And who now remembers the radiogram, the cable, the telegram? They have all passed on into irrelevance. And yet the rain dance and the stone circle and the fireside gathering and the poems and the muezzin’s chant—all of these continue to inform just as they have for thousands of years, people telling people things with calm efficiency and precious little fuss.

Furthermore, it is believed, they are doing so with considerable reverence for the simple existence of knowledge itself. Archaeologists and anthropologists, much of whose business is to divine the meaning and motive of ancient practices from the things they dig up or the customs they discover, seem generally to agree that the passing on of knowledge by whatever means serves two quite distinct purposes.

First, it helps in real time to ensure the health and survival of a community—its survivance, to use a term from the anthropologists’ playbook, meaning something rather more than mere survival, a continuation of tradition by way of the regular connection with the spirits of tribal ancestors, a connection that helps keep “a sense of presence over absence.” Second, the handing on of knowledge helps maintain for the future the very coherence of the community itself, in much the same way as some modern religious rituals—those of the Jewish tradition come to mind—that help to keep a vulnerable community intact, self-aware, and self-confident.

Which is why in most communities—be they Arctic Inuit, Native American, First Nation, Australian Aboriginals, Amazonian rainforest dwellers, New Zealand Maoris, Polynesian islanders, Siberian indigenes—the value of their knowledges is underlined by the immense care taken to guard and then transmit them—by oral tradition of one kind or another, in the main.

“Knowledge keepers,” as they’re called by those academic outsiders who study the rich profusions of ancient humankind, are always carefully selected by community elders. In most Native American tribes, for instance, a promising child may well be chosen early on as a likely candidate for maintaining the tribal knowledges, to pass them on concisely and faithfully in years to come.

The teaching of children, in other words, is where the story of the transfer of knowledge truly begins.

There has in recent years been a tendency among Westerners to wallow in self-mortification, to compare the simple wisdom of the ancients—clichés such as this abound—with the supposed vulgarity, greed, and self-centered thoughtlessness of modern societies. We are these days reminded that climate change, for example, is hardly the fault of the Inuit or the Cherokee or the Samoan, of peoples who we like to believe have long expressed a profound respect for their environment and have taken great pains to ensure that their ways of preserving it are passed on.

Classic and long-remembered books and films—Silent Spring, Koyaanisqatsi, Dersu Uzala, even Mondo Cane—serve to goad us into accepting that peoples often so much more knowing and less greedy than us have taken care of our planet for very much longer than we have been in existence. Such publications have asked: Why do we not do the same? Why did we not follow in their footsteps? Whatever happened?

These are fair questions. Why indeed did the transmission of knowledges that seem so potentially beneficial to us all get to be so drowned out by the noise of commerce and nationalism and war? It is a puzzle unanswered by evidence, other than the purely circumstantial, which suggests one peculiar thing: that the apparent efficiency of writing knowledge down seemed to give it a value that its orally transmitted ancestor would soon no longer enjoy.

Once the transmission method changed from oral to written, once the handing down of thoughts and tradition and culture became mediated by language, once it became properly recordable and fully discoverable, then its hitherto rather obvious value seemed to change profoundly, to evaporate. The medium did indeed become an integral part of the message, in aboriginal societies just as among the more modern, the more advanced.

One might argue that this new form of dialogue—writing—was responsible for the change, the shift in tone. One might say that in writing the authors displayed sentiments that, if not intended for general disbenefit of society, were much less gently constructive than the oral traditions. In the earliest writings, it seems that reverence for our natural world faded quite speedily from public discourse. People just didn’t write down their noble sentiments in the way they had spoken of them so eloquently before. Instead, writing dealt with the more vulgar aspects of society, in tones familiar in the colloquy of today.

The very first written transmission of knowledge ever to have been discovered comes from more than five thousand years ago, on a small tablet of sunbaked red clay found recently in what is now Iraq. The tablet’s cuneiform text is quite bereft of fine sentiments about tradition, nor does it offer noble pronouncements about the environment or high culture.

Rather it is a matter-of-fact notation of the receipt in a Mesopotamian warehouse of a large amount of barley. It is written and signed by a man named Kushim, who appears to have been an accountant. Which, given the dominance of matters financial and economic in the construction of our modern world, seems an entirely appropriate place to begin the story of the diffusion of knowledge.

The document is a perfectly ordinary declaration about the possession of a commodity. It was written down, inscribed, as a record for some later person to come to learn about the commodity’s ownership. It was a piece of mundane, unexciting, quotidian knowledge, and it was presented in written form for one reason only—so that it could be communicated from the original author to someone else later on. It could be diffused, disseminated, and spread around, so that others would, in months or years or decades or millennia to come, be informed about this decidedly unexciting matter. So that these other people could thus, in the small matter of barley storage and sale, become educated.

Given that all of us, in our daily lives, are constantly confronted by a limitless confusion of knowledge, and given that some of this will stick, that some of it we’ll store and retain, one can say that all of us are being educated all the while, and that education is in its essence the business of any transmission of knowledge from one party to another. But at the same time an important distinction needs to be made.

No part of this vast panoply of knowledge diffusion is more important for the future of human society than that which passes in one direction, downward across the generations, from the older members of a society to the younger. The teaching of children, in other words, is where the story of the transfer of knowledge truly begins.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Knowing What We Know: The Transmission of Knowledge: From Ancient Wisdom to Modern Magic by Simon Winchester. Copyright © 2023. Available from Harper, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Simon Winchester

Simon Winchester is the acclaimed author of many books, including The Professor and the Madman, The Men Who United the States, The Map That Changed the World, The Man Who Loved China, A Crack in the Edge of the World, and Krakatoa, all of which were New York Times bestsellers and appeared on numerous best and notable lists. In 2006, Winchester was made an officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE) by Her Majesty the Queen. He resides in western Massachusetts.