How Bob Dylan Became a Counterculture Icon

Aaron J. Leonard on the Political Education of One of America’s Finest Folk Musicians

“A song satirizing the John Birch Society was barred from Ed Sullivan’s television show on Sunday night by the Columbia Broadcasting System, which said it was controversial.”

–New York Times, May 1963Article continues after advertisement“No one can say anything honest in the United States. Every place you look is cluttered with phonies and lies.”

–Bob Dylan, 1963

*

When Bob Dylan released his breakthrough album, The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, in May 1963, many saw it as a revelation. Others, however, saw it as a problem. Depending on how one saw the arrival of Dylan says a lot about where someone would fall out as the disruptions and dislocations of the 1960s unfolded.

Ironically, Dylan himself would not be radically engaged in the most incendiary years of the decade he helped define, his most radical period occupying just over thirty-eight months from the release of Freewheelin’ to his motorcycle accident in July 1966. Regardless, his arrival said much about not only how Dylan was seen by the guardians of American culture, but how they would respond to those who followed him.

The origin myth of Bob Dylan reads something like this. He arrived in New York City in the cold of the winter of 1961, paid a pilgrimage to the hospital where his then idol Woody Guthrie was slowly dying of Huntington’s Chorea, proceeded to busk and hustle his way through the Greenwich Village folk scene before being discovered by New York Times folk music critic Robert Shelton, and was then picked up by legendary Columbia music producer John Hammond, who worked with Dylan on his first, and unremarkable, eponymous record, before striking gold in 1963 with the breakout masterpiece, The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, soon after becoming a living legend who continues to occupy the pop consciousness of millions.

All of which is true, plus or minus a few details, but something essential is missing. Bob Dylan arrived on the scene amid the red-hot embers of the Second Red Scare, and he was, for a time, part and parcel of a left-inclined resurgence in music that was relentlessly opposed by the powers that be. If, in the end, Dylan made his way through to the mainstream, he did so by leaving aside overt political controversies for more nuanced ones.

If, in the end, Dylan made his way through to the mainstream, he did so by leaving aside overt political controversies for more nuanced ones.

At the moment “he became,” however, there was no small amount of energy directed at keeping him marginalized. That he was ultimately not constrained is testament not only to his extraordinary talent, but to the social tumult that allowed him to realize his genius.

*

Dylan, nineteen years old, arrived in New York in January 1961. His first years in the city brought him into intimate contact with the Old Left, with people such as former Communist Party members Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger, Sis Cunningham, and Gordon Friesen, and the then-Trotskyists Dave Van Ronk and Terri Thal. In late 1961, Dylan’s breakthrough came with his meeting John Hammond, who had already caught his eye in the studio where the young Dylan was playing harmonica for the Texas folk artist Carolyn Hester.

Things vaulted ahead further when New York Times critic Robert Shelton reviewed Dylan’s performance at Gerdes Folk City. In a review titled “Bob Dylan: A Distinctive Folk Song Stylist,” Shelton wrote that “his music-making has the mark of originality and inspiration.” For an unknown folk singer in the crowded environment of the early 1960s Greenwich Village folk scene, Shelton’s review was akin to turning a high-voltage floodlight on Dylan.

Shelton himself was a curious character, having an unclear relationship to the Old Left. In 1956, he was called to testify in front of the Senate about his communist affiliations. The problem was that the Senate was actually looking for a Willard Shelton, who also worked at the New York Times. Despite the mistake, Shelton refused to cooperate, garnering a contempt citation. He would spend many years contesting the charge, and faced prison, before the matter was finally dropped. While the exact reasons for his decision to not cooperate are unclear, his failure to do so, in the face of imprisonment, speaks volumes about his adherence to principles.

*

Despite Shelton’s review and Hammond’s support, it was not until 1963 that Dylan fully arrived on the national scene with Freewheelin’, which contained the classic “protests songs”—the popular moniker attached to any music of social criticism—“Blowin’ in the Wind,” “Masters of War,” “Oxford Town,” “Talking World War III Blues” and “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall.” The album also included quite a bit else, including the love songs “Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right,” and “Girl from the North Country.” More than a few of these would become classics, most notably “Blowin’ in the Wind,” when Peter, Paul and Mary—the group created by Dylan’s manager, Albert Grossman—had a hit with the song that same year.

What happened to Dylan’s political sensibilities between his first album, whose only trace of politics was in “Song to Woody,” his paean to Woody Guthrie, and the second, is a matter of conjecture—though it was a period where he began writing his own songs at a feverish pace, upending in the process what his peers in the folk milieu thought possible. In that regard, Ian Tyson tells of how “Dylan came running in one day in about 1962 and he said, ‘Hey, you’ve got to hear this great song I’ve written,’ and we said ‘Written? What do you mean written? Everybody thought he was nuts. You don’t write folk music.’”

That aside, what is known is that he was surrounded by highly political people trying to influence his thinking. For example, Dave Van Ronk—who Dylan was close to in this period—has said:

I was always trying to recruit him, but Bobby was not really a political person. He was thought of as being a political person and a man of the Left, and in a general sort of way, yes, he was, but he was not interested in the true nature of the Soviet Union or any of that crap. We thought he was hopelessly politically naïve, but in retrospect he may have been more sophisticated than we were [laughs ironically].

Van Ronk’s explanation is helpful as far as it goes, but a comment by Sylvia Tyson offers insight into the influence his peers exerted on him:

The thing most people don’t realize about Bob Dylan is that he has a kind of photographic memory for things. He literally remembers everything he’s ever heard or seen. I’ve had him recall conversations we had a year earlier word for word. So he has a wealth of material to draw from in his songwriting. It’s how he gleans from this, how he synthesizes all this, how he put it together that is his real talent.

For a brief while, Dylan was immersed within a very political crowd—by choice—and that could not but have had a profound impact on how, and what, he chose to write about.

Among this circle was his girlfriend, Susan Elisabeth “Suze” Rotolo. Rotolo was the daughter of Mary and Gioachino Pietro (known as “Joachim” or “Pete”) Rotolo, both of whom had been active with the Communist Party USA. As such, they all were subject to significant FBI attention. Rotolo landed on the Bureau’s radar because of her participation in a youth group called Advance, the forerunner of the Communist Party’s “DuBois Clubs”—named after W.E.B. Du Bois. It was because of such ties that the Bureau flagged her when she applied for a passport to travel to Italy with her mother in early 1961, several months before she met Dylan.

Rotolo herself was never a member of the CP, as she explained, “I knew I could never sign on to any political organization. It wasn’t in my nature to follow a party line. I would participate, but I would never join anything.” So while she would work with a group like Advance, she was not a cadre in a Marxist-Leninist organization. But member or not, her associations drew the FBI’s attention and they would maintain a file on her throughout the 1960s. It was not, however, just Rotolo who garnered attention.

Because of her FBI monitoring, we know Bob Dylan was also on the Bureau’s radar—in entries such as “during 1963, the subject [Suze Rotolo] frequently associated with Robert Dylan, a folksinger.” Dylan is also mentioned in regard to the Freewheelin’ cover, with its iconic image of Dylan and Suze walking in the February chill on Greenwich Village’s Jones Street. An affidavit from July 1964, by an employee of the Department of the Army—defined as being “presently assigned as an FBI special agent”—describes how he came across Rotolo’s name while going through FBI documents. He in turn submitted a report to the Bureau, writing, “my wife was fairly close to Susan Rotolo up to about 1956.” He then tells of how:

[L]ast year we heard, through family channels that Susan Rotolo was dating Bob Dylan, the folk singer. In 1963 Columbia Records issued a Bob Dylan recording, [Freewheelin’] and Susan Rotolo appears in a photograph with Dylan on the jacket cover.

The agent’s report closed, noting that, “according to my wife’s immediate family,” Rotolo “has allegedly broken off her relationship with Dylan.” All of which is instructive as to the myriad ways the FBI was gathering intelligence, first by having a “liaison” agent working within Military Intelligence, then by the serendipity of family connections.

Dylan was immersed within a very political crowd—by choice—and that could not but have had a profound impact on how, and what, he chose to write about.

Rotolo’s file would eventually grow to 174 pages—modest by FBI standards, but voluminous given how little it was predicated on. It would remain open until 1974.

*

While Dylan is referenced multiple times in Rotolo’s file, he does not show up in Dave Van Ronk’s—though the two were close in that period. The file does, however, show the FBI visiting the club where both Dylan and Van Ronk performed:

On 2-6-63 inquiry was made at Gerdes Folk City 11 W. 4th St., NYC re subject. It was ascertained that subject was not currently appearing nor scheduled to appear in the near future. However, subject has appeared as a Folk Singer at that establishment in the past.

In similar fashion, the Bureau reported, “On 12/13/63, REDACTED who has furnished reliable information in the past, personally provided a written statement to SA REDACTED,” which described a benefit in Philadelphia for the miners of Hazard Kentucky where the “folk singers were: Phil Ochs and REDACTED.”

That the Bureau was poking around in Philadelphia and at a Village nightclub in pursuit of Ochs and Van Ronk is rather astonishing. That said, by the end of the year, the FBI would open a file on Dylan himself.

*

While Dylan was crossing the FBI’s radar, if vicariously, he came under direct targeting in the private sphere. This occurred when he sought to perform his song ridiculing the ultra-right—“Talkin’ John Birch Paranoid Blues”—on The Ed Sullivan Show, which he had been slotted to appear on following the strength of the Shelton review and imminent release of Freewheelin’. Unfortunately, the powers that be at CBS took issue with his choice. After a successful rehearsal, Dylan was told by Sullivan’s son-in-law, Bob Precht, that he would have to choose another song. Dylan was uncompromising, responding, “No; this is what I want to do. If I can’t play my song, I’d rather not appear on the show.”

While press reports attribute the decision to ban the song to television censors, there was likely more going on in the background, not the least of which was Sullivan’s track record as an aggressive anti-communist. It is hard to imagine Sullivan, and those of his mindset, not being put off by a song that mercilessly ridiculed anti-communism. This might also explain why, while it was reported Dylan would be asked back later, he never appeared on the show. This incident, in turn, impacted the imminent release of Freewheelin’.

In the wake of the controversy, lawyers at Columbia Records, which was owned by CBS—concerned about a libel suit from the right-wing organization—instructed that the song be pulled, despite the fact that copies had already gone out. Regardless, the record company ordered a new pressing, removing it from the album. It would only make an official release in 1991, when Dylan’s first “bootleg” set included a version from his Carnegie Hall performance of October 1963. In introducing the song, Dylan angrily tells the audience, “There ain’t nothin’ wrong with this song.”

__________________________________

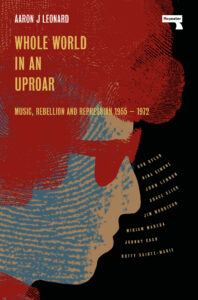

Excerpted from Whole World in an Uproar: Music, Rebellion and Repression – 1955-1972 by Aaron J. Leonard. Copyright © 2023. Available from Repeater Books.

Aaron J. Leonard

Aaron J. Leonard is a writer and historian with a particular focus on the history of radicalism and state suppression. He is the author of Heavy Radicals: The FBI’s Secret War on America’s Maoists, A Threat of the First Magnitude—FBI Counterintelligence & Infiltration: From the Communist Party to the Revolutionary Union, and The Folk Singers and the Bureau: The FBI, the Folk Artists and the Suppression of the Communist Party, USA-1939-1956. He lives in Los Angeles.