How Black Queer Readers and Writers Nourish the Future

Alexis Pauline Gumbs on the Power of Ancestral Connections

In Anguilla they say that my grandmother knew how to control the rain. No one ever told me that she had those powers while she was alive, but on the way to her funeral the rain stopped just in time for us to get out of the cars and walk into one of the several local churches where my grandmother Lydia organized. That’s when my Aunt Una said it: “That’s mommy telling us she’s with us; you know, everyone said she could control the rain.”

I would have loved to ask my grandmother whether she was Storm from the X-Men. But all I have are archival materials that I piece together as a kind of evidence. Yes. My grandmother was the founder of the Anguilla Beautification Society, a group of people committed to growing flowers on a desert island. Yes. My grandfather, who often lived apart from my grandmother, would write letters asking her to send rain. And sometimes he included graphs of the local water table, so it seems he meant it quite literally. When it was time to go through my grandmother’s jewelry and divide it among granddaughters, the necklace that spoke to me was a large turquoise stone, evidence of gathered elements, used in Navajo culture to invite rain. I now wear it almost every day. All that is to say, I can say yes.

My grandmother had a special relationship to rain. Or maybe her water power was a community-held metaphor. My grandmother had that kind of impact, like water in the desert. She nourished the communities where she was planted. She founded hospitals and service organizations; she was involved in all the churches because that was where the people were organized. She even designed the flag during the Anguillian Revolution in 1967. Three dolphins swimming in a circle. Like water nourishing the ground, she made the impossible bloom. And in the years after my grandmother’s death, Anguilla has become so lush and green, you would almost never know it had ever been a desert island. So yes. I have my own reasons to believe in the power of rain.

It was on that same island, Anguilla, vacationing with the scholar and activist Gloria Joseph, that poet, theorist, and icon Audre Lorde began to imagine a new form of fertility for herself. According to biographer Alexis De Veaux (an icon in her own right, also featured in this book), Lorde’s experience in Anguilla inspired her to make a decision that would add years to her life—to move full-time to the Caribbean. Lorde had imagined the Caribbean as a mythical ancestral home because her parents were from Grenada and Barbados, but her time collaborating with the Women’s Coalition in St. Croix and visiting Anguilla helped her decide that living in the Caribbean was practical for her physical health and peace of mind. The decision to live in the Caribbean was also a decision to make roots with another Black woman, Gloria Joseph, another form of homecoming that watered the last years of her life.

Now Anguilla calls herself “rainbow city” and the tourist board markets the country as an island of rainbows. I am almost 100 percent sure that no one on the Anguillian tourist board was inspired by the rainbow symbols of the gay pride flag. Rainbows, which one can see frequently in Anguilla, come from the fact that Anguilla has become a place with short rain showers followed by sun, the wind-propelled variance resulting in prismatic reflection; sunshowers lead to rainbows. Of course, as Audre Lorde would learn in 1989 in St. Croix, too much rain and wind in the Caribbean, the ferocity of the still outraged winds of the transatlantic slave trade routes, can result in devastating hurricanes, and now because of climate change more frequently they do. In 2017, Anguilla experienced the most destructive hurricane in local history.

Oya, the Yoruba goddess of the storm, of change, is also the keeper of the graveyard, the ancestral connector, the helix. Audre Lorde learned from a priest late in her life that she was a daughter of Oya. The hurricane is also represented in Orisha iconography by the rainbow. Was my grandmother a representative of Oya? Family lore suggests she was definitely in touch with her rage, and she was undoubtedly a change maker in her community.

Is it possible for a Black queer relationship to rain to have a tangible impact on the world we find before us? Yes.What does it mean for us, readers, writers in what Briona Simone Jones calls and claims as an expansive Black lesbian literary tradition, to claim an intimate relationship with rain at a time of climate change and wildfires, in a time thirsty for ancestral remembrance and change? Is there a relationship to the legacy of this tradition of women nourishing each other and ourselves, often in spaces that seem hostile to the growth of our love and the healing change our planet needs right now? And is it possible?

Let me tell you another story. Or another part of the same story. Over 150 years ago, after a year of organized intelligence, Harriet Tubman led what may have been the most successful uprising of enslaved Africans in North American history. In the midst of the Civil War, about eight hundred enslaved people stole themselves to freedom, burned down 36 plantation buildings, and flooded the rice fields of the South Carolina plantation owners who were bankrolling the Confederate effort. The night of that successful mission, called the Combahee River Raid, there was a fierce storm. In a transcribed letter, Tubman describes the sounds of the thunder and the rain, and the songs she sang to let the multitude know to get in the Union Army river boats she had waiting.

The next day, Tubman made her first public speech documented in a newspaper. This uprising was the first act against slavery that she could publicly take credit for because it happened in the context of the Civil War and with the support of those most radical members of the Union Army who had ridden with John Brown. This successful strategic influx of power into the Union effort and attack on the Confederacy where it hurt the most was decisive in the Union victory in the Civil War and the de facto end of slavery in the United States.

In the mid-1970s, the members of what was at the time the Boston Chapter of the National Black Feminist Organization decided to create their own organization because they felt the National Black Feminist Organization was lacking in the analysis they needed around homophobia and capitalism. They named their organization the Combahee River Collective because they were inspired by the collective action that Harriet Tubman orchestrated for Black freedom and they saw their work as Black feminist socialist lesbians as a contribution to the freedom of all Black people. Though by the time I was born the Combahee River Collective was no longer an organization, their Black Feminist Statement remains one of the foundational documents of contemporary Black feminism.

Weeks before I turned thirty years old, my partner, Sangodare, and I made our own trip to the Combahee River, the spot where it now flows under the Harriet Tubman Bridge. It wasn’t until we were already on the road that we realized we were traveling to the Combahee exactly 150 years after Harriet Tubman had come to the area to start preparing for her mission. And you won’t believe what happened: three dolphins swam under the bridge, circled each other in the exact formation of the flag my grandmother designed, and swam out to sea. I stood there in my white dress, with my jar of Combahee River water and my grandmother’s turquoise necklace on my heart, and decided with my partner that one year later we had to come back and bring more Black feminists in the legacy of Harriet Tubman and the Combahee River Collective to honor the 150-year anniversary of this collective victory that still reverberates.

So we came back, 21 Black feminists dressed in white, most of us queer. With us was an elder of ours who was mentored by the members of the Combahee River Collective. Demita Frazier, one of the three co-authors of the Combahee River Collective Statement, advised us on our journey and told us that our pilgrimage inspired her to begin renewed work on her much anticipated memoir. On the sunny morning of June 3, we sang, we chanted quotations from the Combahee River Collective Statement like “Black women are inherently valuable” and Harriet Tubman’s mantra, “My people are free.” We recited Tubman’s transcribed letter about the storm that night and imagined what the fleeing multitude might have said at the moment of action. We knew in that moment that what it meant to love Black women was time travel and study, reverence and ceremony. It required all of who we were and who we could become. We knew we had to love the women we were and the women of our lineages, our grandmothers and our great grandmothers, the women we never got to hold, the people coming after us and ourselves and the bridge and an invitation to all of it. And as we fully brought our spirits to that moment in the midst of a sunny day, the sky suddenly opened up and rain fell into our open mouths.

So is it possible for a Black queer relationship to rain to have a tangible impact on the world we find before us? Yes. It is possible. Yes, we can water our decisions with the words of writers. Yes. The words can nourish the futures we deserve.

__________________________________

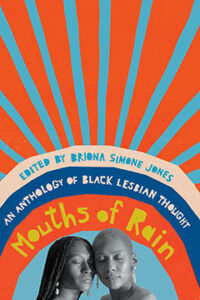

From Mouths of Rain: An Anthology of Black Lesbian Thought, edited by Briona Simone Jones. Used with the permission of The New Press.