How Beyoncé’s “Formation” Embodies the Ethos of Black Womanhood

Catherine Joy White on Black Women's Long History of Resistance and Collective Struggle

“Formation,” Beyoncé’s 2016 anthem that ricocheted across the world after her incendiary Super Bowl performance sang out against police brutality, the government response to Hurricane Katrina, and the idea that Blackness is anything other than beautiful. It simultaneously elevated an unapologetic love for Black culture and, most important, the power of the collective, of a formation.

Throughout the song, Beyoncé moves through time, class, and place as she invokes the different methods of Black resistance. There is the overt expression of deeds not words, familiar to many of us from the cries of the suffragettes. This resistance can look like anything from brandishing guns to staging coups to taking a physical stand. Next, there is the quiet, preparatory, and almost meditative kind of resistance—preparing for a battle of words and ideology. We see this on social media, in interviews, and on television shows.

Then, there is “formation,” an altogether different sort of resistance. Formation is the kind of resistance that places collective action and creativity right at its heart. Just as a dance troupe must get in perfect formation, for this sort of resistance to be successful, there must be total coordination. Black women, as they organize, strategize, move, and create, must get in formation. To do this—to truly create a perfect formation—no piece or person can be missing. Every single member—each contribution—matters and so the formation is also a motor for all of those at the intersection of Blackness and womanhood: queer, trans, nonbinary, working class, neurodiverse, disabled, immigrant—they all belong. They all contribute. They all matter. When you think of it like this, Beyoncé’s “Formation ” is a call to arms.

Every single member—each contribution— matters and so the formation is also a motor for all of those at the intersection of Blackness and womanhood.

The vision of this formation of Black women, in perfect synchrony as they communicate across time, space, and situation, can be seen throughout history and especially in the collaboration of Black women in Europe, Africa, America, and the Caribbean in the early twentieth century. Just like Beyoncé, these women used art, music, and the emergence of new forms of global media to create a literary and political resistance to the dominant narratives of their time about Blackness and womanhood.

Women such as Claudia Jones, born in Trinidad and Tobago in 1915, went on to change the course of history. By the time she died in 1964—at the age of just forty-nine—Jones had transformed the face of the Black Power movement worldwide. After moving as a child from the Caribbean to the United States, she went on to become a communist political activist, feminist, and Black nationalist, eventually leading to her deportation during the McCarthy era’s campaign against those on the political left.

She ended up in the United Kingdom, where she founded the West Indian Gazette, Britain’s first major Black newspaper, and, perhaps most significantly, played a central role in founding the Notting Hill Carnival, now the second-largest annual carnival in the world and a place where arts, culture, and a total celebration of Blackness meet and thrive. Jones defied definition and used her platform not only to advocate for fierce political change but also to promote unashamed self-love. Noticing that many beauty contests time were strictly reserved for white or extremely light-skinned Black people, Jones used the West Indian Gazette as a means of appealing to as many Caribbean people as possible and encouraging them to be proud of their identity and their beauty.

Across the Channel, Caribbean sisters Jeanne and Paulette Nardal had moved from Martinique to France, where they built a political resistance as writers and publishers. They used their language skills to push for cross-cultural communications, writing about everything from Afro-Latin identity to European fetishism of Black women and Black music in the United States.

By using their art to create meaningful connections across the globe, just as Beyoncé did in crafting her own formation a century later, Black women such as Jones and the Nardal sisters were able to carve out new spaces for themselves. They established themselves as writers, activists, and pioneers—forces to be reckoned with. Their resistance was unique because it was two pronged.

At a time when Black men were fighting racism and white women were battling sexism, Black women’s resistance came from a rejection of both sexism and racism, a radical departure from all that had been seen before. It was a resistance made up of those who stood at a crossroads: race, class, gender—every individual standing at an intersection of society was welcome. In my mind, this looks very much like what we now know to be “intersectionality,” a term coined by Professor Kimberlé Crenshaw in 1989 to refer to how the different elements of an individual’s identity come together to establish discrimination and privilege.

Black women’s resistance came from a rejection of both sexism and racism, a radical departure from all that had been seen before.

In fact, Claudia Jones’s 1949 essay An End to the Neglect of the Problems of the Negro Woman actually helped to establish the foundations of intersectionality and feminism as we know them today. The resistance of these women was powerful because it was inclusive. It was inclusive because it was neither the overt bravado and spectacle of a physical resistance nor the subtle musings of an intelligentsia lost in libraries and private correspondence. Rather, this was a resistance born out of creativity and connection.

As the Nardal sisters opened their literary salons in Paris in the 1920s to all who passed through, Claudia Jones was joining America’s Young Communist League. Theirs was a shared resistance that took place in churches and in kitchens and was frequently overlooked. Just as you may not notice individual dancers as they performance sequence, but rather marvel at the wonder of the collective, so has history blurred the names and faces of the individual Black women getting in formation.

Millions of people celebrate Notting Hill Carnival each year, but how many know that its founding mother is a Black woman? How many know that she played a part not only in fighting for racial equality in the UK, but in bringing Caribbean culture to the forefront of British life? How many people know that she was deported, arrested and sentenced to prison four times, or that she was responsible for the first televised Black beauty competition in the UK? How many people know that she dedicated her life to liberating her own Black people?

Much of the societal progress that we see today, one example being the now deeply valued cultural institution that the Notting Hill Carnival has become, can be traced back to the work of our foremothers. Their resistance—their formation—used creativity connections to lift those who came after them.

__________________________________

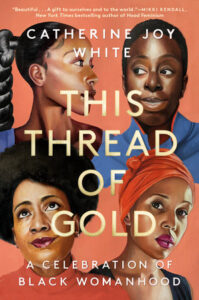

From This Thread of Gold: A Celebration of Black Womanhood by Catherine Joy White. Copyright © 2024. Available from Tiny Reparations Books, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.

Catherine Joy White

Catherine Joy White is an actor, writer, filmmaker, and founder and CEO of the award-winning Kusini Productions, a company established to champion the voices of Black women. She is a gender advisor to the United Nations, and she has been honored as a member of the Forbes 30 Under 30 Class of 2022. She starred in Amazon Prime’s Ten Percent, the UK adaptation of Call My Agent, and worked on the latest Black Mirror alongside Salma Hayek Pinault. Her films have been funded by the BFI and the BBC, and have won awards at BAFTA and Oscar-qualifying festivals worldwide. She wrote and directed To My Daughter, a film starring Gugu Mbatha-Raw, which was adapted from a chapter in This Thread of Gold. She has a Master’s Degree in Women’s Studies from Oxford, and an undergraduate degree from the University of Warwick. She lives in Oxford, and this is her debut book.