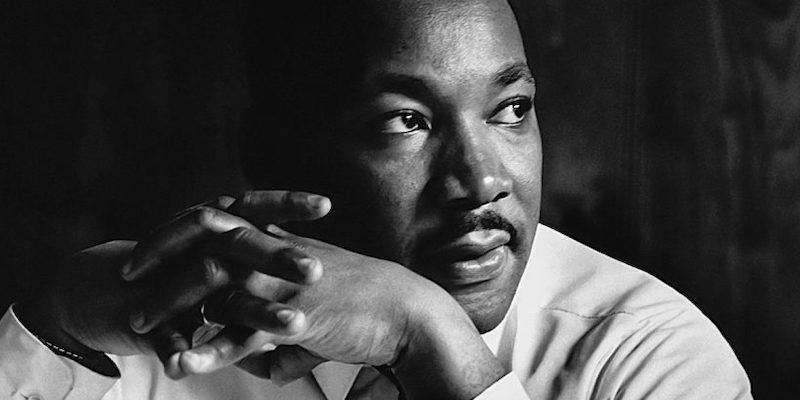

How Bayard Rustin Inspired Martin Luther King Jr.’s Nonviolent Activism

Jonathan Eig on the Early Civil Rights Movement and the Making of "Alabama's Gandhi"

Martin Luther King, Jr. stood on the porch of his tiny Montgomery parsonage. An agitated crowd of neighbors gathered around him, waiting for his orders.

King’s home had just been bombed. His wife, Coretta, and his infant daughter, Yolanda, had been in the house at the time. They escaped unhurt. King rushed home upon hearing the news of the attack and found his neighbors gathered on the lawn and in the street. White police officers and city officials stood by, nervously, fearing the mostly Black crowd might turn violent.

“We believe in law and order,” King told the crowd. “Don’t get panicky. Don’t do anything panicky at all. Don’t get your weapons. He who lives by the sword shall perish by the sword. Remember that is what God said. We are not advocating violence…I want you to love our enemies. Be good to them. Love them and let them know you love them. I did not start this boycott. I was asked by you to serve as your spokesman. I want it to be known the length and breadth of this land that if I am stopped, this movement will not stop. If I am stopped, our work will not stop. For what we are doing is right, what we are doing is just. And God is with us.”

The date was January 30, 1956. The Montgomery bus boycott was in its second month. At the age of twenty-seven, King found himself thrust unexpectedly into a role of leadership. As his remarks from his damaged front porch make clear, he was not yet a committed follower of Gandhi. He had read and studied the Indian political activist and ethicist, as well as other proponents of nonviolent protest, but Gandhi’s tactics and philosophy were not yet at the fore of his mind. King’s calls for love and forgiveness, at that point, were inspired by Jesus, and by the commonly held view among Black leaders at the time that justice would never be won through violence. King remained ambivalent about nonviolence. He made that much clear after the dynamite attack on his home when he applied for a gun permit. He faced real danger, and he was prepared to defend himself and his family if necessary.

Rustin saw a chance to extend the Montgomery model, and he recognized quickly that King might be the partner he needed.But things were changing rapidly. America had never experienced anything like this protest in Montgomery, former capital of the Confederacy, former hub of the Alabama slave trade, and current defender of racial segregation. Black people had united in bold defiance of Jim Crow laws, standing up to the Ku Klux Klan, the police, and the city’s all-white lineup of lawmakers. For two months, the people had refused to ride the city’s segregated buses, refused to participate in a system and way of life that sought to batter and belittle them. King urged them to embrace the power of nonviolence for largely practical reasons: to stake out the position of moral superiority in confrontation with those who assumed and sought to enforce Black people’s inferiority.

King captured the imagination of his followers in Montgomery, across church and class lines. He emboldened the community. He also excited progressive activists around the country. The activists saw potential for a nationwide movement, a movement rooted in resistance, built around the Black church, and led by Black people, with the brave, brilliant, and highly telegenic Martin Luther King guiding them. One of those activists, the novelist Lillian Smith—a board member of an international pacifist group called the Fellowship of Reconciliation—wrote to King on March 10, 1956, with advice. “You can’t be an expert in nonviolence; it’s like being a saint or an artist: each person grows his own skill and expertness,” she wrote. But if King decided he wanted to try to grow as an expert and practitioner of nonviolence, Smith added, if he wanted to explore the potential application of Gandhi’s tactics in the United States, he would do well to talk to Bayard Rustin.

Rustin, as it turned out, had not been waiting for an invitation from King. He had reached Montgomery days before Smith’s letter, eager to see if he could help King use nonviolent tactics to extend the reach of his campaign. Rustin was forty-five years old, and he had already been a part of some of the century’s most important protests. He had worked with FOR, the War Resisters League, and A. Philip Randolph’s Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. The fact that he was gay was an open secret among activists. The fact that he had been a member of the Young Communist League was no secret at all. His arrival in Montgomery marked a turning point, not only in King’s life but in the history of America radicalism and rebellion.

Nonviolent protest was hardly a novel idea in 1956. Nearly a century before King’s birth, the white abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison had called for the use of passive resistance to attack slavery. Decades later, labor unions had used sit-down strikes and factory seizures to demand better pay and working conditions. Throughout the 1940s, A. J. Muste, Asa Philip Randolph, and others had led campaigns of nonviolent protest, including marches and boycotts, inspiring activists such as Rustin, James Farmer, and Montgomery’s E. D. Nixon to look for opportunities to organize protests of their own.

In a letter dated February 21, 1956, just prior to his arrival in Montgomery, Rustin announced his goal: “to bring the Gandhian philosophy and tactic to the masses of Negroes in the South.” Nothing short of strict adherence to nonviolence throughout the South, he wrote, “can save us from widespread racial conflict.” Rustin saw a chance to extend the Montgomery model, and he recognized quickly that King might be the partner he needed.

When he arrived at King’s tiny parsonage in Montgomery, Rustin was pleased to discover that he had already met King’s wife, Coretta, having lectured years prior to her class at the Lincoln School in Marion, Alabama. Rustin never said whether he remembered meeting Coretta, and it seems unlikely that any one student in the class would have stood out, even one so impressive as Coretta.

Nevertheless, Coretta remembered Rustin. Years later, King’s friend and colleague Ralph Abernathy would say Coretta played a key role in King’s decision to embrace Rustin as an advisor in those early days of the boycott in Montgomery. Coretta’s endorsement mattered. At that point, she had had more experience than her husband as an activist. As an undergraduate at Antioch College in Ohio, she had joined the campus chapter of the NAACP, a race relations committee, and a civil liberties committee. She had challenged a rule that prevented Black students from student-teaching in local schools. One fellow student recalled that Coretta had also joined in a protest when a barbershop in Yellow Springs had refused to cut Black people’s hair. In 1948, she had supported Henry Wallace and the Progressive Party for president and attended the party’s national convention as a student delegate. In the early days of the Montgomery bus boycott, Coretta was her husband’s most important advisor.

Rustin presented a risk for King. Enemies of the bus boycott would call out the presence of this gay man with a background in communism to smear and sidetrack the protest movement. But King could see that Rustin had a level of experience others in Montgomery lacked. Rustin knew the major figures in the civil rights movement and understood the interplay of the big organizations. Almost immediately, the men engaged in a “very long, philosophical discussion of nonviolence,” as Rustin recalled.

In years to come, Rustin would complain that King was too cautious at times, that his desire for consensus prevented him from making the tough decisions required of a leader. But King was hardly cautious in his initial acceptance of Rustin. King had always had an appetite for big ideas, and Rustin helped him conceive of his protest in the grandest terms, terms that firmly linked three of his greatest interests—philosophy, religion, and social justice. In Montgomery, the pieces were coming together for the greatest nonviolent movement America had ever seen, and they were coming together in no small part because King and Rustin had the vision for how the pieces might be arranged, because King proved willing to adapt, and because these two men managed to forge a complicated but dynamic working relationship.

In his first visit to King’s house in Montgomery, Rustin saw armed guards stationed outside and a pistol on a chair in King’s living room. When Rustin asked about the weapons, King replied, “We’re not going to harm anybody unless they harm us.” To Rustin, that did not sound like a Gandhian approach. King knew that many Black southerners owned guns. He also knew that supporters of the boycott were risking their lives standing up to Alabama’s system of white supremacy. Alabama had seen 360 lynchings since Reconstruction. A violent white response to the Black uprising was all but guaranteed. As King’s remarks from his blasted front porch made clear, he recognized the possibility of escalating violence. Rustin argued that a violent outbreak would be a disaster for the movement and for the Black people of Montgomery, that Gandhian protest required a rejection of all violence, even in self-defense. Glenn Smiley, another FOR activist who had arrived to help the movement, reported in a letter from Montgomery that King recognized that the presence of armed bodyguards undercut his nonviolent message, but King didn’t seem to mind the contradiction. “He believes and yet he doesn’t believe,” Smiley wrote.

Rustin and other activists recognized that King, perhaps uniquely, had the ability to lead a movement that forged deep and wide cultural and political change.King’s journey was underway. He began to read more Gandhi and to refer to him more often in speeches and sermons. He discarded the gun he had purchased for personal protection and ordered the men protecting his home to do so without weapons. Rustin recalled telling King that he would have to make a deep commitment to nonviolence for his message to have an impact. King’s followers, like his bodyguards, were unlikely to fully embrace nonviolence, Rustin said. They didn’t have to. If King convincingly adopted the philosophy and if his followers sensed their leader’s dedication, they would adhere to his instructions. They would follow him. They would protest nonviolently, even if they didn’t devote their lives to nonviolence. And that would be enough.

The more King mentioned Gandhi in speeches and sermons, the more the national media latched on to the nonviolent element of the Montgomery protest story. Reporters—especially reporters from the North—saw a classic morality tale, one that starkly separated the good guys from the bad guys. King’s commitment to peaceful protest gave his movement an aura of moral superiority. Reporters began referring to him as “Alabama’s Gandhi.” Not everyone bought it, of course. “The man is a genuine intellectual,” wrote Grover C. Hall, editor-in-chief of the Montgomery Advertiser, in reference to King. “But that constant Gandhi business of his, that love-those-who-hate-you routine is the biggest bunch of nonsense I’ve ever run into.”

But the anger generated among people like Hall helped King’s cause. The more the protesters were threatened and attacked by segregationists in the South, the more support the protesters received from Black southerners and liberal white northerners. King became a central focus of the growing racist fury for the same reasons he became a beloved figure among his followers—because he spoke so beautifully and so calmly and because he maintained his insistence that the segregationists who wanted to shut him down and perhaps even cause him physical harm were, in fact, his brothers in Christ. King emerged from Montgomery as the nation’s most visible and influential Black leader. He held no national office. He possessed no great political clout. He attracted only modest financial support. His power derived primarily from his high moral standing and from his extraordinary voice—a voice that resonated with a broad audience, from poor, Black men and women in the South to wealthy liberals in the North. Rustin and other activists recognized that King, perhaps uniquely, had the ability to lead a movement that forged deep and wide cultural and political change.

In early March, Rustin wrote to A. Philip Randolph, recommending that King and others organize a workshop on nonviolence in Atlanta, one that would bring together Black leaders from across the South for a discussion about nonviolent protest. Rustin understood the organizational power of the Black church, having seen its force in Montgomery. The gathering in Atlanta took place less than a year later. It would lead to the creation of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and it would lay the groundwork for much of the course of King’s future as an activist. The entire blueprint was there, in the documents Rustin prepared for the meeting; the preachers would advise and support more protests like the one in Montgomery, demanding integration with nonviolent protests, threatening economic consequences for segregationists, and pushing for the federal government to expand voting rights for the disenfranchised Black residents of the South.

Though their methods were radical, the movement’s leaders were not. They were men of God, their words imbued with nobility and love. Most of them were family men, well educated, conservative in dress and lifestyle, hardly the bomb-throwing radicals many Americans associated with protest movements. They believed they had found a method by which, at last, they might achieve not just integration but a reckoning with the sins of slavery and a path to a new and more equitable society.

__________________________________

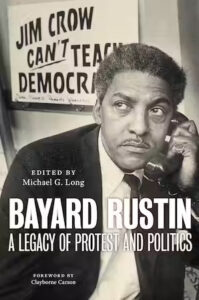

Excerpted from Bayard Rustin: A Legacy of Protest and Politics, edited by Michael G. Long. Copyright © 2023. Available from NYU Press.