How Baseball Shaped Black Communities in Reconstruction-Era America

Gerald Early on the Early History of Black Participation in America's Pastime

From the end of the Civil War to World War I, African Americans experienced extraordinary change. In one respect, they went from being enslaved people to citizens, from slavery to freedom, in a complete redefinition of a people. The ratifications of the Thirteenth Amendment (December 1865), which ended slavery; the Fourteenth Amendment (July 1868), which granted citizenship; and the Fifteenth Amendment (February 1870), which granted Black men (but not yet women) the right to vote, radically changed the civic and political status of Black people in an amazingly short period of time.

In addition, the Civil Rights Act of 1866 ensured equal protection under the law, and the Civil Rights Act of 1875 banned racial discrimination. Black leaders obtained political office in some Southern states, including sixteen who were elected to Congress, two who served in the U.S. Senate, and two who served briefly as governors during Reconstruction (1865–1877), the period when the United States experimented with being a multiracial democracy.

But if the elevation of Black Americans during Reconstruction was a revolution, it was met by a fierce counterrevolution on the part of white Southerners who vehemently and violently opposed any change in the status of Black people. White Southerners utterly opposed the Freedmen’s Bureau, a federal agency established to help newly freed African Americans obtain fairer wages and better employment conditions from their former enslavers; the bureau also established, in conjunction with the American Missionary Association, some HBCUs (historically Black colleges and universities). But its main work ended in 1869, and the bureau closed for good in 1872, at which time it had not had nearly enough time to achieve the goal of helping a mostly impoverished people become self-supporting citizens.

Black citizens were climbing a steep hill, but they were willing to do so, in part because so many of them believed in this country, even if the country did not believe in them.

White Southerners formed terrorist organizations, like the Ku Klux Klan, that brutally intimidated Black citizens and created Black Codes to nullify African Americans’ new rights. Barely a year after the end of the Civil War, in May 1866, Memphis erupted in one of the worst racial pogroms of the Reconstruction period. White people, provoked because Black soldiers had stood up to racist white (mostly Irish) policemen, rampaged through the Black community of Memphis, killing 46 Black people, injuring over 75, and burning to the ground every Black school and church in the city. The Colfax Massacre in Louisiana in 1873 resulted in the murder of somewhere between 62 and 153 Black citizens who had surrendered after resisting a white attempt to take over the local courthouse.

Despite Frederick Douglass’s efforts as the last president of the Freedman’s Savings Bank, including lending it $10,000 to keep it afloat, the bank’s failure in 1874 destroyed the faith of millions of Black people in the country’s financial institutions. The lack of will on the part of the federal government and “the friends of the Negro” to enforce the social and economic changes that Reconstruction had promised left Black Americans feeling betrayed, powerless, and further impoverished by the 1880s. With the failure of Reconstruction, Black people were no longer fully empowered citizens but political and social ciphers. As Malcolm X once told a Harlem audience, “You’re nothing but an ex-slave.” The Confederates may have lost the Civil War, but the southern counter revolutionists won the race war that followed.

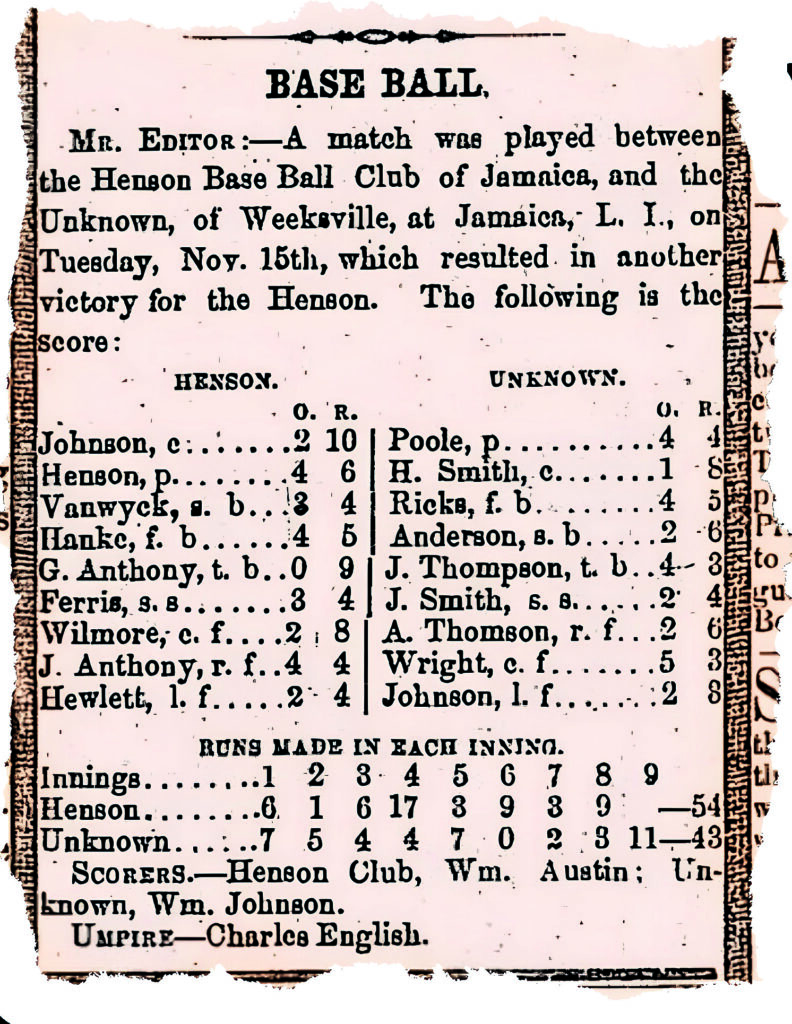

Photo credit: December 10, 1859 edition of the Anglo-African

Photo credit: December 10, 1859 edition of the Anglo-African

Out of this cauldron of hope, then chaos and repression, Black people gave the world spirituals and ragtime and, in 1900, their own national anthem, “Lift Every Voice and Sing.” Segregated and virtually exiled, the all-Black Twenty-Fourth and Twenty-Fifth Infantry regiments, two of the regiments known as the Buffalo Soldiers, and the Ninth and Tenth Cavalries fought in the grim wars in the West against Native Americans. Black units also fought in Cuba and the Philippines during the Spanish-American War.

It can hardly be said that Black people did not serve their country, even as their country scarcely acknowledged them. They built schools and churches and started newspapers. The literacy rate among Black people in 1870 was 18.6 percent. It had jumped to 55.5 percent by 1890. Between 1890 and 1900, the number of Black physicians and dentists nearly doubled, thanks to HBCUs. Surely, Black citizens were climbing a steep hill, but they were willing to do so, in part because so many of them believed in this country, even if the country did not believe in them. Alas, between 1890 and 1900, 1,217 African Americans were lynched—a form of white social engineering at its most brutal. For Black citizens, believing in this country was not easy.

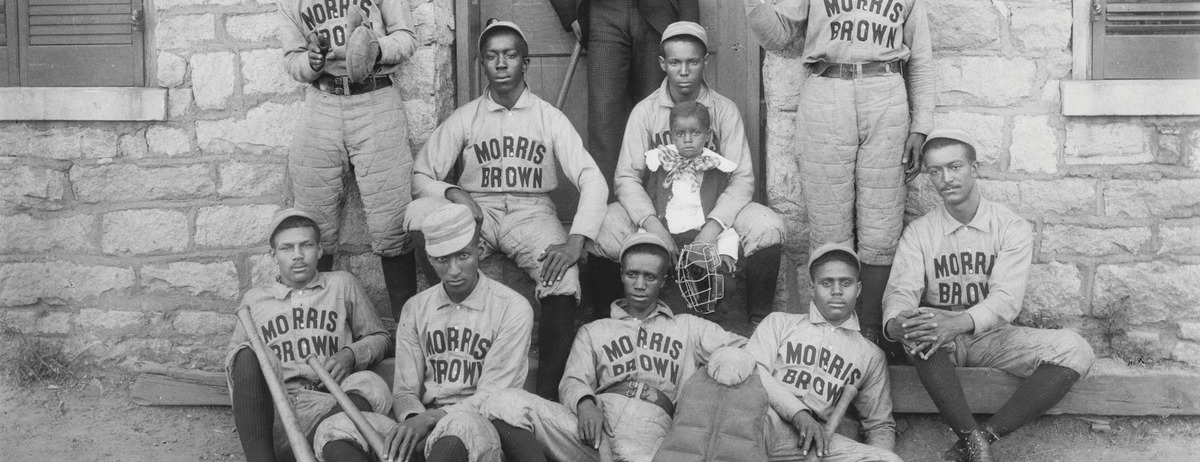

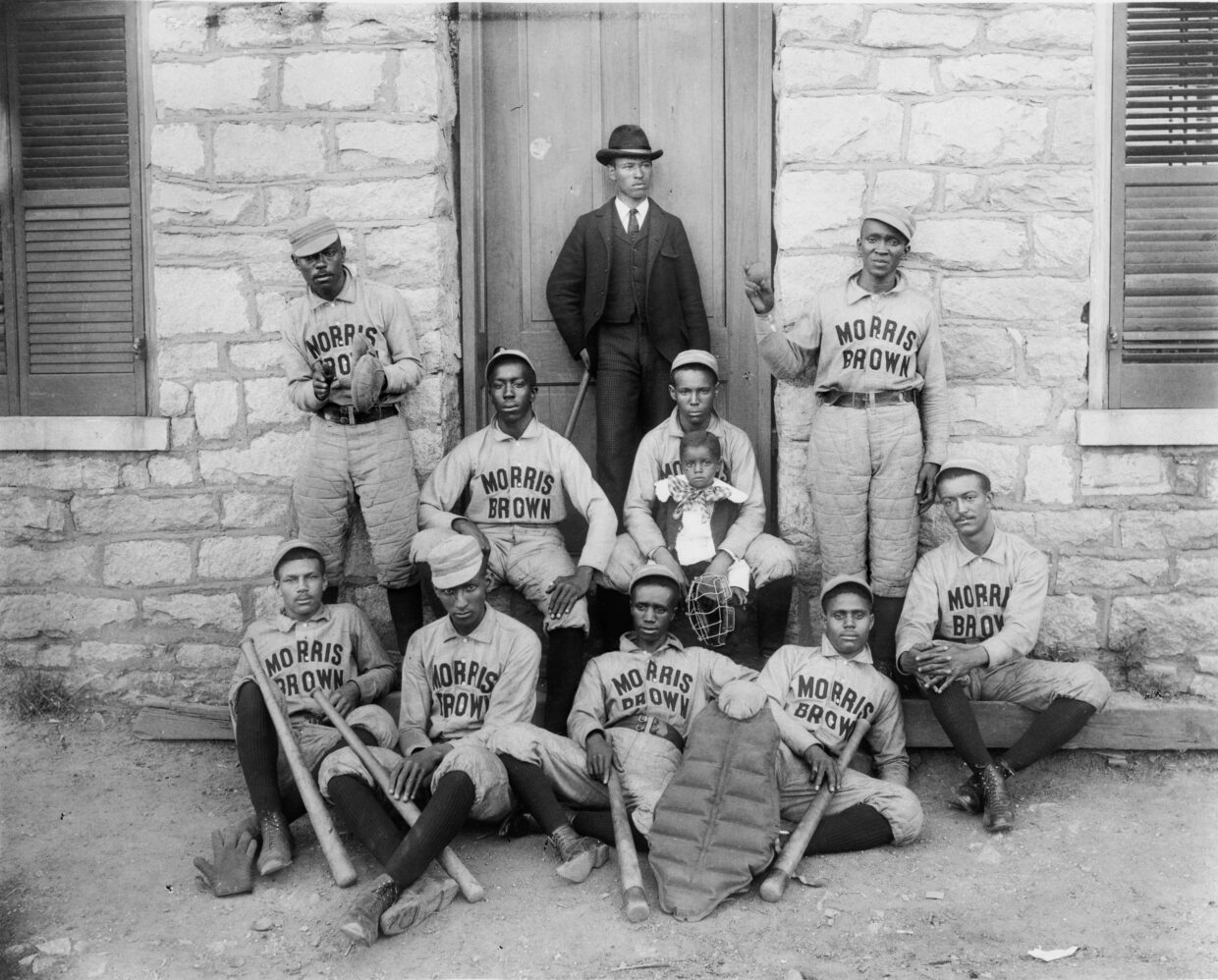

And most notably, perhaps quixotically, groups of Black athletes, against considerable odds but with firm dedication, played baseball. During Reconstruction, during the launch of the Jim Crow era, when local and state laws legalized segregation in the South, and at the nadir of race relations at the turn of the twentieth century, they organized teams and sought competition with great energy. Nay, even more—there were Black people in America who loved baseball more than just about anything else.

*

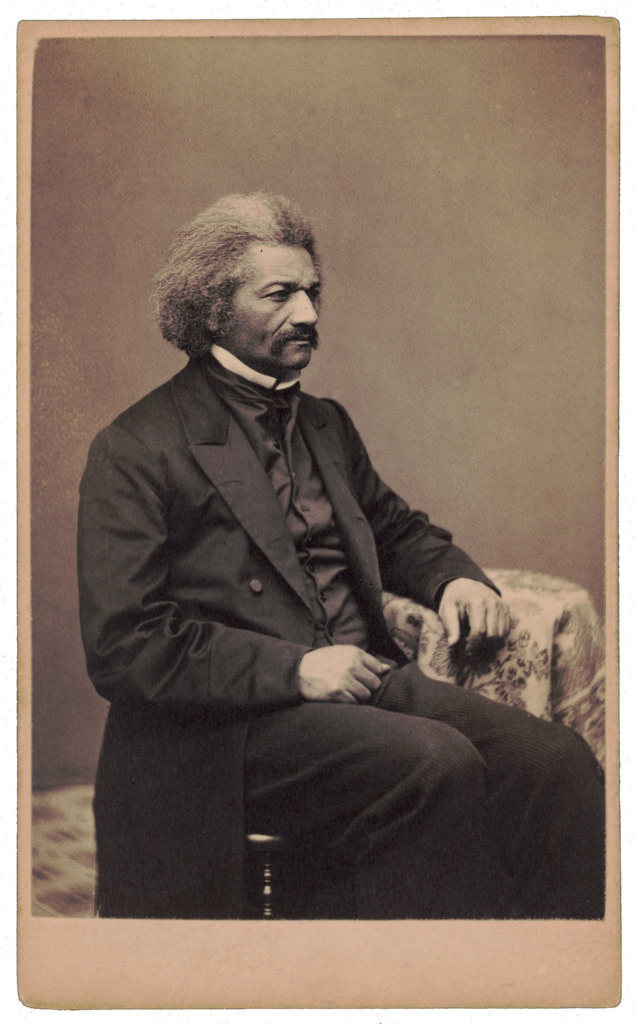

In his 1845 Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, Douglass wrote in some detail about the holiday periods on the plantation, the week between Christmas and New Year’s Day. During the holiday season, some enslaved people were permitted to earn money in order to improve their condition or to save up for their ever-elusive freedom. “But by far the larger part,” Douglass observed, “engaged in such sports and merriments as playing ball, wrestling, running foot-races, fiddling, dancing, and drinking whisky; and this latter mode of spending the time was by far the most agreeable to the feelings of our masters.” Douglass asserted that the masters wanted the enslaved to waste the holidays, to not be productive or seek any form of self-improvement.

Photo credit: Library of Congress

Photo credit: Library of Congress

Douglass’s theory was that the master wanted this small taste of freedom to be a dissolute, gluttonous experience to warp the enslaved peoples’ sense of what freedom was and to make them more amenable to returning to work when the holiday ended. Two things in this passage are notable. First, among their activities, the enslaved people played a ball game of some sort that historian Michael E. Lomax claims was a form of rounders or town ball. If this is true, it would mean that an early version of baseball was played on some Southern plantations in border states in the 1830s, which was when Douglass was enslaved in Maryland. (He escaped in 1838.)

Second, Douglass disapproved of the various sports the enslaved people played, as well as fiddling” and “dancing.” He classed all these activities with “drinking whisky,” which Douglass, a firm temperance supporter, abhorred. Douglass thought that any activity that pleased the owners was not in the enslaved peoples’ interest. Besides, these activities seemed frivolous, not in any way moving the enslaved mentally and emotionally toward freedom, nor in any way opposing the system of slavery. In fact, to Douglass’s way of thinking, they reinforced it.

But whatever Douglass thought of sports on the plantation during slavery, he saw matters differently with the advent of freedom. His youngest son, Charles, who was twenty-three years old in 1867 when he started working for the Freedmen’s Bureau, was a fervent player. More than that, he was an organizer on a Black team in Washington, D.C., called the Alerts, immediately after the Civil War, when Black baseball teams began appearing in the East.

Indeed, when Charles’s father attended an Alerts game, it made headlines in New York: “Fred Douglass Sees a Colored Game.” Many government workers like Charles Douglass played baseball (or “base ball,” as it was written at the time). In fact, the White House lawn was a popular site for play. Despite Black interest in a game that had a considerable white following and much white participation, there was no mixing of the teams and not much interracial play. Racial lines had already been drawn.

Douglass helped his son Charles raise money for the team, and for Black baseball generally, by writing a letter urging Black Washingtonians to support the Alerts team. He donated his own money as well. When his son switched teams to become the president of the rival Black Washington team, the Mutuals, joining his brother, Frederick Jr., Douglass Sr. switched his allegiance as well, becoming an honorary Mutual in September 1870. It is not overstating to say that Douglass was a baseball man. He attended games, supported his sons’ involvement, and even played catch with his grandchildren.

Douglass’s support gave Black baseball an imprimatur of race approval as an activity that uplifted the race. It was not frivolous for Black men to pursue this sport as an avocation, or even as a vocation. Baseball conveyed a kind of Black social capital. Black men as ballplayers were seen as entrepreneurs, as “manly” (which they were not when enslaved), as supporting a meritocracy and having standards of excellence, and as being role models to Black children.

They were also playing the American game and thus underscoring their identification as American and their right to make such a claim. After the debacle of the 1857 Dred Scott Supreme Court decision, which held that Blacks were not citizens and were never intended to be, such a claim was not to be taken lightly. If the Black public could not make a claim as Americans, what could they make a claim to being? For Black people after the Civil War, playing baseball was not a way to a future, but the way of the future.

*

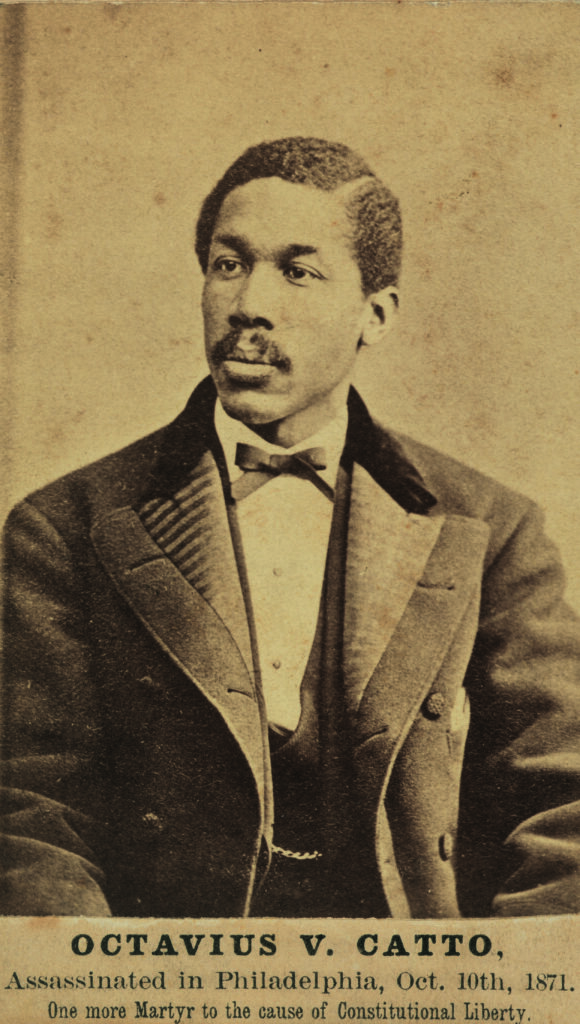

In his pathbreaking sociological study The Philadelphia Negro (1899), W. E. B. Du Bois mentions “the cold-blooded assassination” of “an estimable young teacher, Octavius V. Catto.” Du Bois footnotes the entire article in The Philadelphia Tribune (a Black newspaper) chronicling Catto’s murder and his funeral, which covers nearly three full pages of his book.

Photo credit: Library of Congress

Photo credit: Library of Congress

Catto, a race activist, was killed on October 10, 1871, election day in Philadelphia, where a fierce battle between Democrats and Republicans took place in the races for mayor, district attorney, and city controller. Black men in Philadelphia, nearly all Republican, had been given the right to vote two years earlier, and this was the first election to put their new right to the test. Aided by the police, white toughs and vigilantes, mostly members of the Irish working class and the Democratic Party, roamed the streets, physically intimidating Black voters. Catto, who had closed his school, the Institute for Colored Youth, early in the afternoon because of the unrest, was shot to death by a white “peacekeeper” near Eighth and South Streets as he was preparing to join his Black National Guard unit. Catto was armed, but never had a chance to use his weapon, as he was shot at nearly point-blank range.

Catto, arguably, had one of the biggest funerals ever afforded a Black man to various departments to permit employees to attend the funeral. Most of the important Republican leaders of the city were there. He was given an honor guard, and his body lay in state at the City Armory. Thousands crowded the streets to pay their respects, many having come from New York City, Washington, D.C., and Baltimore. The Philadelphia Tribune article that Du Bois ran in full said much about Catto, except one thing: in addition to his roles in the military, as an educator, and as a Black civic leader, he was a baseball player. Du Bois never mentioned it, either.

Catto’s team was the Pythians, which premiered in 1866, as much a social club as a baseball outfit. Club members rented rooms at the Institute for Colored Youth, where the strict rules included no gambling, no liquor, no profanity, and no conduct that would redound unfavorably to the race. These men were largely mixed-race and would have been considered the Black Philadelphia elite. Du Bois would have called them “the Talented Tenth,” just the sort of college-educated Black elite he felt was necessary to lead the race. The Pythians were gentlemen of breeding, and playing baseball was meant to enhance their respectability.

Other Black clubs called themselves the Blue Stockings or the Giants, but the Pythians showed their cultural aspiration in their name, a reference to ancient Greece and the Olympic Games. As with the white clubs of the period, the Pythians, like the Mutuals and the Alerts in Washington, were amateurs, not professionals. These men, for the most part, were not common laborers but, like Charles Douglass, had white-collar jobs. They had the leisure time and the money to play baseball.

Like Washington, Philadelphia had an active and long-standing Black elite with two aims: to serve as a bridge or liaison to white elites, and to be exemplars to lower-class Black citizens. In essence, the Black leadership class tried to balance two pursuits: gaining access to white institutions and organizations in an effort to remove racial stigmas and gain equal civic and economic opportunity; and creating Black institutions and enterprises that showed self-reliance, intelligence, the solidarity of the race, and a commitment to self-improvement.

If the source of any hard feelings was the status of the freed and newly created Negro citizen, the easiest solution was to keep the Black population as a subordinate, inferior group.

That Catto was an activist is hardly surprising. According to Daniel R. Biddle and Murray Dubin in Tasting Freedom, the entire leadership of the Pythians came from “abolition and Underground Railroad families,” the antebellum Black activist elite that included fugitive slave lecturers, writers, and organizers like James W. C. Pennington, William Wells Brown, and Frederick Douglass.

The Pythians acquitted themselves well against rival Black teams in Philadelphia, a city that would remain a hotbed of Black baseball through the days of the Negro Leagues. They played both the Mutuals and the Alerts, in Philadelphia and Washington, in games that were not only competitive but highly social, as the home team would always host a huge meal after the game. To be a successful Black team required that the Pythians be highly organized, with a committee to secure a field and umpires (a challenge for Black teams that would continue into the Negro Leagues era, as white teams controlled baseball spaces), a committee responsible for transporting the team if they were the visitors, a committee to work on the after-game feast or picnic if the Pythians were the host, and a committee to select a trophy or prize for the opposing team.

The team practiced twice a week and held monthly meetings; for Catto, an additional obligation was running the Institute for Colored Youth. Dues were five dollars a year. The drawn-out schedule of meetings and practices indicates that early Black baseball was played at a leisurely pace as an amateur game. When it became professional, many more games would be played to try to keep both the league and individual teams afloat.

In October 1867, Raymond J. Burr, the Pythians’ vice president, attended the convention of the Pennsylvania Association of Amateur Base Ball Players (PAABBP), held in Harrisburg. Baseball at this time held a number of conventions and meetings, local, statewide, and national, as it stabilized and codified its rules and established league affiliations. The Pythians had applied for full membership in the PAABBP. They had had a successful 1867 season, becoming one of the best Black clubs in the country. Their play received regular press in the Sunday Mercury and The Philadelphia Inquirer. Burr was the only Black person at the convention, but was treated courteously, even collegially at times. However, the Pythians’ application was denied—in fact, Burr withdrew it when it was clear that it had no chance of success. Had the Pythians been a white club, their acceptance would have been pro forma.

Photo credit: Library of Congress

Photo credit: Library of Congress

The reason for the rejection was purely racial, as granting a Black team membership would have been tantamount to recognizing Black men as equals; most white Northerners were not keen to do this, in part because such a gesture would have stymied sectional reconciliation. The Civil War was over, and there was now no reason for Southern and Northern white people to foster hard feelings against one another. If the source of any hard feelings was the status of the freed and newly created Negro citizen, the easiest solution was to keep the Black population as a subordinate, inferior group, socially and politically. This accommodation of the South by the North made Reconstruction half-hearted and was the reason it ultimately failed.

For baseball’s future, as white Northerners saw it, getting white Southerners committed to the game as the National Pastime was crucial. This feeling only intensified in the latter part of the nineteenth century as white Southerners propagated the myth of the Lost Cause, which made them seem like tragic heroes rather than traitors. And so, the Pythians’ failed try at PAABBP membership was the first official step in the codified segregation of baseball.

At the 1867 National Association of Base Ball Players (NABBP) convention, the nominating committee issued a statement barring the membership of any Black club or any club with a Black member. This move appeased NABBP president Arthur Gorman, a founding member and a pro-Union Democratic Southerner from Maryland. He was also a star player with the Washington Nationals, which was formed in 1859 and recognized as America’s first “official,” high-caliber, nationally known baseball team.

Gorman served only one year as the NABBP president, solely as a postbellum gesture of reconciliation. He was, as author Ryan Swanson perceptively, if wryly, points out, “ ‘an affirmative action’ hire,” as he was selected solely because he was a white Southerner. The NABBP’s ban of Black teams and players was the second major precedent that eventually led to a segregated baseball system in the United States. This segregation in the sport was to grow, reaching its peak by the mid-1880s, even before Jim Crow was fully nationalized and made constitutional with Plessy v. Ferguson’s “separate but equal” decision in 1896.

The death of Catto was the end of the Pythians. The club seemed to lose heart and direction, not only because of the death of its most important leader but especially because of the way he died. But Black baseball soldiered on, its story just beginning. A new class of Black ballplayers was coming, the men who played for money—the professionals.

__________________________________

From Play Harder The Triumph of Black Baseball in America by Gerald Early. Copyright © 2025 by Gerald Early and The National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Inc. National Baseball Hall of Fame trademarks and copyrights are used with permission of the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Inc. Illustrations copyright © 2025 by Oboh Moses. Published by Ten Speed Press, an imprint of Crown Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.

Gerald Early

Gerald Early, a noted essayist and cultural critic, is a professor of English, African, and African American Studies and American Culture Studies at Washington University in St. Louis. He is the author of several books, including The Culture of Bruising, which won the 1994 National Book Critics Circle Award for criticism.