How Astronaut Class 8 Broke Racial and Gender Barriers

Meredith Bagby on NASA's Earliest Efforts at Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion

“Judy Resnik,” Dr. Christopher Kraft said into the microphone.

As Judy walked across the carpeted stage, she blinked back the bright lights from the reporters’ flashing cameras. This isn’t a dream, she reminded herself, heading to one of the plastic scoop-back chairs set out on the stage. Earlier in the day, Judy dressed for the event, straightening her naturally curly hair and putting on a white button-down shirt, a below-the-knee skirt, and conservative heels.

Now, seated next to Sally Ride, Judy crossed her ankles and folded her hands gently in her lap, as prim and proper as a charm school student. As the rest of the thirty-five astronauts filled the stage in order of last name, the scene looked more like a high school graduation photo than the announcement of NASA’s next astronaut class.

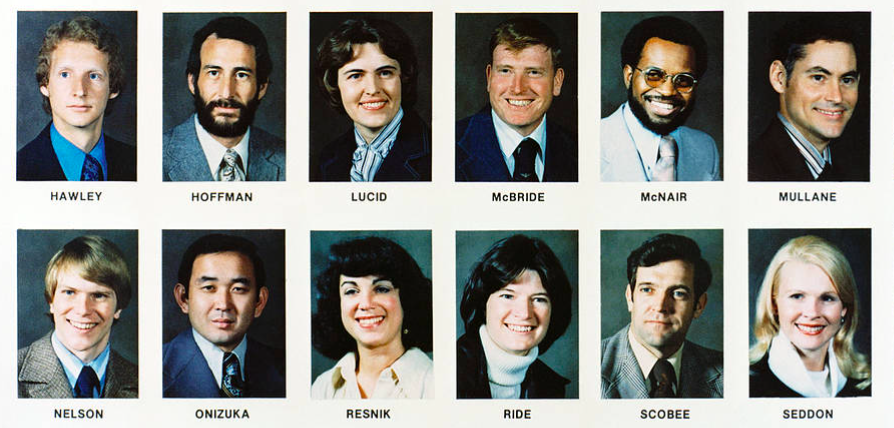

Two weeks prior, on January 16, NASA had released the names of its newest astronauts. All three major networks—ABC, CBS, and NBC— headlined the story. “NASA chose the thirty-five persons who will ride the space shuttle to orbit and back,” reported CBS News’s Walter Cronkite. “Among them are three Blacks, one Oriental, and six women: Ronald McNair, Fred Gregory, Guion ‘Guy’ Bluford, Ellison Onizuka, Anna Fisher, Shannon Lucid, Judy Resnik, Sally Ride, Rhea Seddon, and Kathy Sullivan. Godspeed to the newest generation of astronauts.” For weeks, print, radio, and television reporters had hounded the new recruits, calling them at their homes and showing up unannounced at their workplaces and universities, but today was their official introduction to the world.

Many were upending the social rules established by former generations and challenging revered institutions.

Born during and after World War II, these men and women had come of age in the revolutionary 1960s. Their teenage and college years began with the optimism of John F. Kennedy’s presidency, but faded into disillusionment during Vietnam, Watergate, and the assassinations of their young leaders—Martin Luther King Jr., John and Robert Kennedy, and Malcolm X.

They lived through and participated in political protests and upheaval on their university campuses and in their cities. Many were upending the social rules established by former generations and challenging revered institutions. Compared to their predecessors, they were more open-minded, free-thinking, and resistant to patrician rules.

Astronaut Class 8 looked like none before it. Gone were the rows of buzz cuts and dark suits that typified every prior astronaut group. Yes, there were the usual military pilots of old: Twenty-one were military officers, nineteen of whom had served in Vietnam. But now, there were civilians, too: doctors, engineers, chemists, physicists, earth scientists, and astronomers. They came from twenty-six states and twenty-seven different academic institutions. They were atheists, Jews, Buddhists, Protestants, and Catholics.

They ranged in age from twenty-six to thirty-eight. At least one was gay, although no one knew it at the time. They wore flared collars, polyester suits, and turtlenecks. Some of the women donned skirts, heels, and jewelry. Others wore smart slacks and colorful scarves. Some of the men sported full beards. When Judy’s class walked on stage for the first time as a group, everyone could feel the new energy, the uptick in tempo. NASA was about to be transformed.

The moment was decades in the making. Since its founding twenty years prior, NASA had excluded women and minorities from its astronaut corps for reasons as complex as the era itself. The way America’s space agency came into existence lay at the heart of the issue.

*

NASA was born out of conflict. Less than a decade after the USSR developed an atomic bomb, its successful launch of Sputnik all but shattered America’s faith in its own technical superiority. In 1958, President Eisenhower responded with an ambitious plan to match and eclipse the USSR’s technological prowess, creating the National Aeronautics and Space Agency: NASA.

The choice to limit astronaut selection to the military defined a generation of astronauts and precluded women from applying altogether.

NASA’s goals loomed large. Funded with over seven billion dollars for its first five years, NASA would coordinate all American space activity. Eisenhower designated NASA as a civilian organization, privately hoping to avoid infighting between the military agencies over space and curb the military’s ballooning budget. Publicly, he promoted NASA as an agency for all mankind. In practice, the notion that space would be accessible to all types of people would be a long time coming.

After much debate, NASA administrators decided that its astronauts should be culled exclusively from the armed forces, whose members had experience handling dangerous conditions and classified information. More important to Eisenhower, NASA trainers could test military candidates quickly and secretly, shielding the agency from scrutiny or embarrassment in front of the Soviets.

Administrators further narrowed their qualifications for the astronaut position in a brief announcement: “men less than 40 years of age, under 5 feet 11 inches, a graduate of a test pilot school, holder of a bachelor’s degree or equivalent, having a total of 1,500 hours of flight time, and qualifying in high-performance jet aircraft.” These test pilots, who assessed the military’s experimental aircraft, were the subject of Tom Wolfe’s The Right Stuff—adrenaline junkies who thrived on putting their “hide on the line” every single day. Within four months of the announcement, NASA selected the Mercury 7—a homogenous group of seven white military men.

The choice to limit astronaut selection to the military defined a generation of astronauts and precluded women from applying altogether. Following World War II, women could join the military, but they were prohibited from aircraft combat and could only comprise 2 percent of the enlisted force and 10 percent of the officer class.

In 1967, Congress repealed the later restrictions, and by the mid-1970s female pilots were allowed in the Navy and the Air Force, but still restricted from the combat positions. People of color fared little better; the armed forces remained segregated as late as 1948. In the 1970s, there were relatively few Black officers and even fewer Black test pilots.

The white military pilots that filled the astronaut corps quickly entrenched themselves, demanding that the Mercury space capsule prioritize pilot decisions over automated systems. They cultivated an image that their test pilot skills embodied the beating heart of space travel.

With racial protests roiling at home, Murrow thought the launch of the first Black man might paint a better image of America abroad.

As the program matured beyond the Mercury 7, NASA stretched astronaut qualifications to include scientists and pared back its flight experience requirements. The agency recruited Neil Armstrong even though he was no longer active military and accepted John Glenn without a college degree. Still, NASA managers refused to open the door to women and people of color. “I do not think that we will be anxious to put a woman or any other person of a particular race or creed into orbit just for the purpose of putting them there,” said NASA administrator James Webb in 1962.

On April 12, 1961, the Soviets wowed the world and embarrassed America with yet another space triumph. Yuri Gagarin achieved global renown as the first human to orbit Earth. Coupled with the calamitous Bay of Pigs invasion, John F. Kennedy’s presidency was gasping for air. In urgent need of political capital, Kennedy looked to the stars. On a warm, sunny day in September 1962, Kennedy spoke to a crowd of more than forty thousand people at Rice University and challenged the country to put a man on the moon before the end of the decade.

“We set sail on this new sea because there is new knowledge to be gained, and new rights to be won, and they must be won and used for the progress of all people,” Kennedy told the crowd and the nation. “We choose to go to the moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard; because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills.”

The challenge captured the imagination of a generation. Congress followed suit with financial support, sending NASA’s budget soaring to $5.25 billion in 1965.20 The new Apollo effort meant new jobs as NASA built out its facilities: the Manned Spacecraft Center in Houston, Texas (later the Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center); the Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama; and the Launch Operations Center at Cape Canaveral, Florida (later renamed after President John F. Kennedy). The Apollo program employed four hundred thousand Americans and required the support of over twenty thousand industrial firms and universities.

As America embarked on the Apollo program, President Kennedy, who campaigned on the promise of equality, worried that racial inequities in the space program were becoming too glaring to brush aside. The executive director of the National Urban League, Whitney Young, urged Kennedy to consider a Black astronaut to get African American youth interested in science and technology.

Meanwhile, Edward R. Murrow, a broadcast journalist who parlayed his experience to lead the United States Information Agency, further nudged Kennedy. With racial protests roiling at home, Murrow thought the launch of the first Black man might paint a better image of America abroad. “Why don’t we put the first non-white man in space?” Murrow wrote to NASA administrator James Webb. “We could retell our whole space effort to the non-white world, which is most of it.”

__________________________________

Excerpted from The New Guys: The Historic Class of Astronauts That Broke Barriers and Changed the Face of Space Travel by Meredith Bagby. Copyright © 2023. Available from William Morrow, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Meredith Bagby

Meredith Bagby is a nonfiction writer as well as film and TV producer. Her previous books include: We’ve Got Issues, Rational Exuberance, and an ongoing series, The Annual Report of the USA. She produces with actress Kyra Sedgwick under the shingle, Big Swing Productions. Previously she was a senior film development executive at DreamWorks SKG. Bagby was a political reporter and producer for CNN and a teaching fellow at Harvard’s Institute of Politics. Her education includes Columbia Law School and Harvard College.