How Antarctic Explorers Kept Themselves Sane on the Voyage

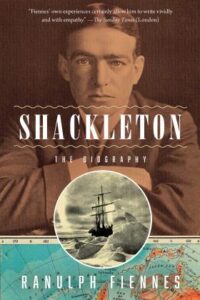

Ranulph Fiennes on the Trials of Ernest Shackleton

The Royal Geographical Society encouraged the Royal Navy to support British expeditions of Antarctica in the early 1900s. Heading from New Zealand, the expedition ship Discovery anchored off the coastline of the unknown land under the leadership of Captain Robert Falcon Scott. He chose the Anglo-Irish ex-Merchant Navy Third Officer, Ernest Shackleton, to lead the first hazardous sledge journey inland over slippery surfaces at temperatures as low as minus 62 degrees Fahrenheit. They aimed to make history by breaking the furthest South record towards the bottom of planet Earth.

Both men succeeded separately, over the next ten years in hellish conditions, to open the way to the South Pole. Scott became famous through the courageous manner of his death and Shackleton through his remarkable 18-month survival story, which ended when his ship, the Endurance, sank. He died in January 1922, 100 years ago, on another Antarctic voyage.

*

When cocooned in the darkness for months on end, many on Antarctic expeditions have lost their minds. This is no surprise, especially for those experiencing it for the first time. It is not only dark, cold and claustrophobic, but being marooned on a mysterious land thousands of miles away from civilization can be difficult to get your head around. These pressures would take their toll on even the most hardened of individuals. Indeed, on the Belgica expedition, the crew succumbed to a mix of scurvy and “cabin fever.”

Even those on the Discovery who kept their sanity found the conditions difficult. As temperatures outside dropped to as low as minus 62 degrees Fahrenheit, most decided to stay on board, but even then, ice still formed on the cabin walls. In these uncomfortable conditions, many of the men grew homesick, while being trapped in the same place and seeing the same people, for months on end, quickly began to grate. Any natural tendency to irritation, depression, pessimism or worry was magnified and, in the absence of loved ones, the natural, indeed the safest, outlets for pent-up feelings were diaries and letters home. That’s human nature, and even more so on an expedition where sensibilities can become extreme.

I found on my first expedition south that forced togetherness breeds dissension and even hatred between individuals and groups. Because of this, at times, I found it very difficult to interact with my fellow teammates Oliver Shepard and Charlie Burton. Some days, without a word being spoken, I knew that I disliked one or both of the other men, and I could tell that the feeling was mutual. I was, however, very fortunate that at base I had Ginny to keep me company, who was always a tremendous comfort and support. With my wife by my side, I could at least let off some steam to her; failing that, I would vent my spleen in my diary. It is quite funny now, looking back, as some of my gripes were so inconsequential, but at the time they felt like major disagreements.

In those dark winter months, with the wind howling outside, Clarence Hare, Scott’s steward and the youngest man on board, revealed there were frequently quarrels and fights among the crewmen. This was where Shackleton truly came into his own.

In charge of the ship’s entertainment, he had ensured that the library was stocked with books while he helped put on plays and even arranged debates, going head to head with Bernacchi over the poetic merits of Browning and Tennyson, with Shackleton arguing for Browning. The crew eventually voted for Tennyson, albeit by a single vote.

Perhaps Shackleton’s greatest contribution to keeping the crew occupied and entertained was the South Polar Times. In the sanctuary of an “office” that was boxed off in the hold, Shackleton sought to publish this journal once a month, inviting the crew to submit any scientific articles, stories, poems, drawings or jokes. Wilson’s illustrations featured heavily, as did Barne’s caricatures of the crew, while Shackleton always found time to contribute a poem, written under the pseudonym Nemo, the hero of Jules Verne’s Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Sea. Calling one of his poems “To the Great Barrier,” in it he alluded to uncovering the mysteries of Antarctica:

This year shall your icy fastness resound with the

voices of men,

Shall we learn that you come from the mountains?

Shall we call you a frozen sea?

Shall we sail Northward and leave you, still a Secret for

ever to be?

There were also plenty of other things to keep the crew entertained. In the privacy of a small cabin, the men could “sport the oak” (contemporary public-school terminology for masturbation), and food was always something to look forward to. This was particularly true for the officers, as Scott did all that he could to make mealtimes an event, with fine china and engraved cutlery being set out in the wardroom.

Shackleton himself could also be relied upon as a great source of entertainment, always eager to share stories or a joke. A deckhand wrote, “He was a very nice gentleman, always ready to have a yarn with us.” As had always been the case, he could mix with anybody and was liked by most.

One of the crew that Shackleton especially enjoyed spending time with was 27-year-old Frank Wild. After eleven years in the Merchant Navy, Wild had enlisted in the Royal Navy just a year previously but, craving adventure, had signed up for the expedition. In this respect, he was very similar to Shackleton and it was easy to see why they got on so well. But it was still with Wilson that Shackleton spent most of his time. After a meteorological observatory had been set up on nearby Crater Hill, both men volunteered to regularly take the readings, even if it meant climbing the hill in the darkness and bitter cold.

Shackleton explained, “We want to do as much exercise . . . as possible, and this will be a useful way of so doing.” This no doubt allowed them some welcome time away from the ship, from which the always patient Wilson had previously complained “there is absolutely no escape,” but it also had a far greater purpose: for Shackleton to prove to Scott that he should be selected as part of his team to go south when the summer finally commenced.

Places to join Scott on his expedition south were highly coveted; it was for this reason that many of the men had signed up in the first place. There was no one more willing than Shackleton. He certainly was not there just to make up the numbers. From the time he told tall tales to his sisters about becoming a famed hero he had dreamed of an opportunity like this. Now, it was within touching distance—as long as Scott selected him.

When selecting team members for my own polar expeditions, I always tried to choose confident, highly capable individuals who, although not “yes” men, would not threaten my status as leader. It’s a difficult mix. While you need people who can think and act quickly under pressure, you don’t want to have to deal with any attempted mutinies on the ice. Sometimes, it’s impossible to tell how people will react until they’re tested in some of the harshest conditions known to man.

Scott, therefore, had a difficult decision to make, particularly as he favoured taking only one other person with him. In this he had been inspired by Fridtjof Nansen, whose famed north polar wanderings had been undertaken with only one companion. With just one place up for grabs, Armitage was the strong favorite. He had actually been promised a place on the main southerly journey right from the outset, hence why he took the position as Scott’s second-in-command. However, as time had passed, Scott had slowly but surely grown to depend on the solid character of Edward Wilson. Having already proven himself on the ice, Wilson was also intelligent and good company. Furthermore, he was a doctor, which could prove vital on such a hazardous journey.

In mid-June, and having had a chance to observe all likely candidates during the winter months, Scott informed Wilson that he would be travelling south. Wilson was stunned. He had only joined the expedition to study the wildlife and geology. Indeed, he had no real inclination to go south, as he revealed in a letter to his wife, complaining that the journey would be “taking me away from my proper sphere of work to monotonous hard work on an icy barrier for three months.” There was also something of a question mark surrounding Wilson’s health. While he was now apparently well, he had initially been turned down for the Discovery expedition, as he had suffered a bout of tuberculosis that left him with permanent lung damage, something that could prove debilitating on a long trek in freezing conditions.

In the circumstances, Wilson felt there was any number of people who could have been chosen ahead of him. However, in spite of all the reasons not to go, he could not turn the opportunity down. “My surprise can be guessed,” he wrote. “It is the long journey and I cannot help being glad I was chosen to go.”

Wilson might have been bemused by the decision, but Shackleton was devastated. Although Shackleton was quick to pass on his genuine congratulations to his friend, he became downbeat and withdrawn. Suddenly, the one real chance to make a name for himself, to be etched forever into the history books, looked to be over. All that would remain was further months marooned on the ice, away from Emily, waiting for Scott and Wilson to return. It was a demoralizing prospect. But Shackleton wasn’t out of the running just yet.

Wilson was concerned that, with just the two of them out on the vast Barrier, if one should be incapacitated, it could prove fatal to the other. In private, Wilson therefore suggested to Scott that perhaps he might consider taking Shackleton as well. After some thought, Scott realized that Wilson’s reasoning made some sense. Shackleton had already proven his worth on the glacier, and he was a powerful man, capable of man-hauling for hundreds of miles. He was also resourceful and good company. It was therefore settled. Come October, the three of them would set off, aiming to make history, hoping to, at the very least, break the furthest south record of travel towards the pole.

After a number of polar expeditions with one companion, and others with two, I look back and can see that things were always easier with just one other person. With only two of you, each time the leader makes a decision that the other person disagrees with, the latter will usually chew the matter over in their mind and will usually do as they are told. But with three, if two disagree with the leader’s decision, they might discuss it among themselves and an awkward mini-revolt may result. Even if this fails, it can lead to a bad atmosphere. If I lived all my expeditions over again, I would never take a third party if it could be avoided (unless one member of the group was my wife). As the old saying goes, “Two’s company, three’s a crowd.”

For the beleaguered Shackleton, this was a tremendous stroke of good fortune. He was of course “overjoyed” when Scott asked him to become the third man for the great trek south, although, once again, not everyone shared his cheer. When the news broke there was a considerable amount of discontent from some of the crew. They could understand Scott taking Wilson, because he was a doctor, but they felt that the other place should surely have gone to a naval man.

Armitage was particularly angry, writing bitter things about Scott for many years to come. Skelton also found it hard to bite his tongue, writing, “Shackleton gassing and eye-serving the whole time . . . of course the Skipper’s ideas are on the whole perfectly right . . . but . . . why he listens to Shackleton so much beats me—the man is just an ordinary gas-bag.” Yet no matter what anyone thought, Shackleton was Scott’s man and his decision was final.

With final preparations underway, and August bringing increasing hours of sunlight, Shackleton was tasked with attempting to train the dogs on the ice. This was a tall order; Shackleton had no experience, and the rowdy and undisciplined dogs were especially difficult to tame. Neither whipping them nor friendly persuasion worked particularly well, and Shackleton was too impatient to persevere for long with either.

Some critics (including Scott in his own diary) suggested that he should have started his dog-team trials earlier than he did, even doing so under the winter moonlight. But such a course could easily have led to severe frostbite and dead dogs, as Amundsen’s Norwegian team was to experience some years later. Starting dog trials at the end of August, near his base, as Scott did, was undoubtedly the most sensible timing. Although he was not totally convinced by their performance, Scott eventually concluded that the dogs made things slightly less difficult than no dogs.

In the meantime, Armitage was at least given a consolation prize for missing out on the journey south. On September 11, 1902 he set out with five men to find a route to the Magnetic Pole, where Earth’s magnetic field lines come vertically out of the surface. Finding this location would be crucial to the updating of magnetic maps of the southern hemisphere and thus to marine navigation. In contrast, the geographic South Pole, which Shackleton hoped to reach, is the place where all the lines of longitude converge in the southern hemisphere. For their journey, Armitage and his team all took skis, a decision about which a still-skeptical Scott commented, “I am inclined to reserve my opinion of the innovation.”

However, as Armitage led his men to an inlet named New Harbour, two of them, Ferrar and Heald, became very ill. Closer investigation revealed that they were both suffering from an affliction that would threaten the success of the expedition: scurvy.

Scurvy caused bruising, weakened muscles, could lead to tooth loss, severe joint pain and, in the worst cases, death. Today, we are well aware that scurvy is the result of a lack of vitamin C. However, this wasn’t the case at the turn of the last century. Certain patterns had been picked up over time, particularly that men near shore and eating fresh fruit, vegetables and meat seemed to be immune from the disease. It seemed most common when men were on long voyages, away from these things. Once they returned to the coastline and ate a heavy diet of fresh seal and penguin meat, they miraculously recovered, but no one yet realized that the crucial element was vitamin C.

__________________________________

Adapted from Shackleton: The Biography by Ranulph Fiennes. Used with the permission of Pegasus Books. Copyright © 2022 by Ranulph Fiennes.