How (and Where) Menstrual Leave Became Policy

Anita Diamant on the Evolution of Equitable Treatment

The medical establishment has been wrong about menstruation—wittingly and unwittingly—for a very long time. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, doctors warned that the strain of riding a bicycle or going to college was too much for women to handle, especially while on their periods. In the 1960s, as women started to enter the workforce in large numbers, premenstrual syndrome (PMS) became the source of a thousand jokes about how women became irrational and overemotional, unable to control the urge to eat ice cream or drop nuclear bombs—pretty much the same baloney ascribed to menopause.

In 1964, Patsy Mink, then a newly elected member of the US House of Representatives from Hawaii, was quoted saying, “I wouldn’t see anything wrong with a woman president.”

Dr. Edgar Berman disagreed. “Suppose that we had a menopausal woman president who had to make the decision on the Bay of Pigs or the Russian contretemps with Cuba?” said Berman, a member of the Democratic Party’s Committee on National Priorities. She might be “subject to the curious mental aberration of that age group.”

Mink wasn’t having it. “His use of the menstrual cycle and menopause to ridicule women and to caricature all women as neurotic and emotionally unbalanced was . . . indefensible and astonishing.”

Dr. Berman called Mink’s response “a typical example of an ordinarily controlled woman under the raging hormonal imbalance of the periodical lunar cycle.” Soon thereafter, the doctor “resigned” from the committee with a whine, saying, “The whole world seems to be uptight.”

The whole world went on to elect at least forty-six women heads of state, beginning with Indira Gandhi in 1966.

The Indian state Bihar has provided two days of monthly menstrual leave since 1992, apparently without incident.

Fifty-one years after Dr. Berman’s remarks, Donald Trump gave voice to the old menstrual libel after TV anchor Megyn Kelly prefaced a debate question to the then-candidate by saying, “You’ve called women you don’t like fat pigs, dogs, slobs, and disgusting animals.” Denying nothing, he smirked that he’d only used those words to describe one particular woman.

Later, when asked about this exchange, Trump said that Kelly had, “Blood coming out of her eyes. Blood coming out of her wherever.”

Jaws dropped, but when he was called on it, Trump claimed he was talking about blood “coming out of her nose” and anyone who thought otherwise had “a dirty mind.”

Given that the millions who menstruate daily are exceptionally skilled at keeping that fact a deep dark secret, a well-intentioned public effort to shed light on it created a minor firestorm in 2019 when a Japanese department store requested that saleswomen consider wearing a “Little Miss Period” badge when they were menstruating.

Little Miss Period—Seiri-chan—is the heroine of an award-winning manga series by Ken Koyama. Seiri-chan is a walking cartoon uterus that visits menstruating women every month and punches them in the gut with painful cramps, but she’s not all bad; in one issue she travels back in time to visit Yoshiko Sakai, the woman who produced the first commercial menstrual pads sold in Japan.

When Little Miss Period became the star of a live-action movie—played by a life-size stuffed animal—the Daimaru department store opened a new boutique department selling Seiri-chan merchandise, clothing, and period products—something they had never sold before. That was when the Seiri-chan badges appeared on the lapels of menstruating salespeople.

The store went on the defense; no one was required to wear the badge, nor were they intended to let customers know anyone’s menstrual status. Their purpose was only to encourage co-workers to be more considerate and offer to help lifting heavy objects.

The badges were scrapped. Or as the company put it, “re-thought.” Menstruation does not cause upper body weakness. However, up to 20 percent of women suffer from dysmenorrhea: cramps, headaches, dizziness, nausea, and diarrhea severe enough to interfere with normal activities for a few days. For most employed menstruators who have those symptoms, options are limited: call in sick and use one of a limited number of sick days; lose a day’s pay or risk getting fired; or go to work and tough it out as best you can. The other—still rare—possibility is menstrual leave, where employees can take paid or unpaid days off without prejudice.

Japan implemented a menstrual leave policy in 1947, when the country needed women workers to join a workforce decimated by the war, but the idea was not widely adopted. Fifty-plus years later, other Asian nations followed suit: South Korea in 2001, Indonesia in 2003, and Taiwan in 2014. But because those laws are rarely enforced, employers have largely ignored them, and women rarely ask for time off for fear of losing their jobs.

There are a few examples of successful government-mandated leave. The Indian state Bihar has provided two days of monthly menstrual leave since 1992, apparently without incident. Zambia passed a “Mother’s Day” law in 2016, guaranteeing a monthly day off for all women, whether or not they are mothers and whether or not they are menstruating. The rationale for calling it “Mother’s Day” was to acknowledge the caregiving work done almost exclusively by women, which is laudable although it assumes men do not now nor ever will have family obligations and responsibilities. Some women have managed to create their own personal time-out. Jeanette MacDonald, a Hollywood star of the 1920s and ’30s, had a clause in her contract that allowed her days off for menstruation like many other actresses. This benefit was not public knowledge, but Clark Gable knew and he grumbled about having to work when his hemorrhoids were acting up.

Menstrual leave is a contentious idea.

On March 8, 2020, International Women’s Day, Shashi Tharoor, a member of the Indian parliament, posted an online petition proposing national laws so that “all employed women in India should have an option to take ‘work from home’ or ‘leave with pay for two days every month, by private and public employers.’” It cited Article 42 of the Indian constitution: “The State shall make provision for securing just and humane conditions of work and for maternity relief.”

The backlash was furious. Journalist Barkha Dutt reprised a fiery opinion piece she’d written for the Washington Post years earlier, calling the idea “a bizarrely paternalistic and silly proposal to further ghettoize us.” She wrote that period leave “may be dressed up as progressive, but it actually trivializes the feminist agenda for equal opportunity, especially in male-dominated professions. Worse, it reaffirms that there is a biological determinism to the lives of women Remember all those dumb jokes by male colleagues about ‘that time of the month’?”

Feminists are divided on the question of menstrual leave; some view it as progressive and inclusive, others reject it as regressive and a threat to gains women have made.

A number of small-to-medium-size businesses and nonprofits have instituted a monthly day off or allowed menstruating workers to work from home, but menstrual leave is still such an outlier among larger companies that the international press was all over the news that Zomato, one of India’s largest food-delivery firms, had instituted ten days of leave a year for its four thousand employees, 35 percent of whom are women.

Feminists are divided on the question of menstrual leave; some view it as progressive and inclusive, others reject it as regressive and a threat to gains women have made. Professor Elizabeth Hill, who studies menstrual leave at the University of Sydney in Australia, notes a generational divide in the debate: “It’s almost as if the over-40s are horrified by the idea while, anecdotally, a lot of the younger women are like, ‘yah, that’s a great idea.’”

Hill says that the conversation about menstrual leave raises a much more fundamental question. “It challenges the notion of the ‘ideal worker’ who is care-less and body-less.” In other words, as interchangeable as widgets.

To date, the rules about work have been written by and for men who have few (if any) caregiving responsibilities, and whose bodies do not regularly change over the course of a month. Also to date, the struggle for gender equality at work has required women to act as though they do not have periods. In the paradigm that worker = male, menstrual leave consigns women to a separate or inferior status—it makes them a problem.

When the happy day arrives when everyone agrees that (1) women are people and (2) workers are not robots but human beings with bodies and souls, the workplace will be reconfigured to provide safe bathrooms with free period products and the means for their disposal—also baby-changing stations and accommodations for people with disabilities.

But the more-essential change goes far beyond the bathroom. Treating all workers as human beings requires generous sick leave, work-at-home options, and paid personal days so that nobody is penalized for taking time off for a menstrual migraine or to bring a sick child to the doctor.

__________________________________

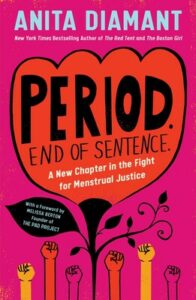

Excerpted from Period. End of Sentence.: A New Chapter in the Fight for Menstrual Justice by Anita Diamant. Copyright © 2021 by Anita Diamant and Melissa Berton. Excerpted with permission by Scribner, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Anita Diamant

Anita Diamant is the bestselling author of the novels The Boston Girl, The Red Tent, Good Harbor, The Last Days of Dogtown, and Day After Night, and the collection of essays, Pitching My Tent. An award-winning journalist whose work appeared in The Boston Globe Magazine and Parenting, and many others, she is the author of six nonfiction guides to contemporary Jewish life. She lives in Massachusetts. Visit her website at AnitaDiamant.com.