How Ancient and Modern Greek Helps Us Make Sense of Greece Today

Nick Romeo on the Tradition of European Explorers in Greece

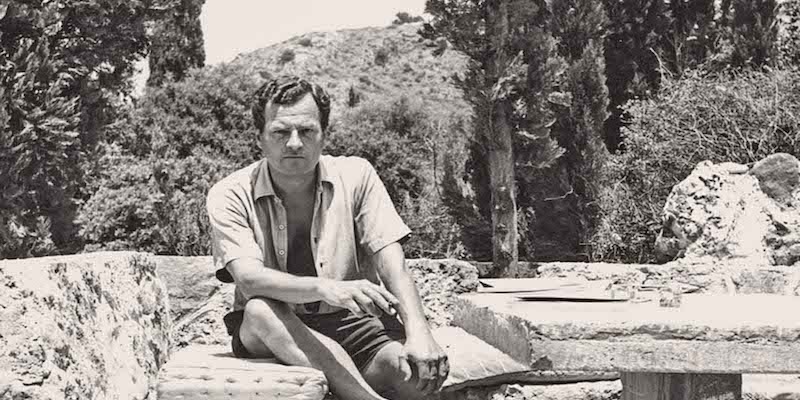

Late one night in 1951, two Englishmen were wandering downtown Athens after an evening drinking in its tavernas. Passing beneath the Acropolis, they decided to scale its rocky north side and sneak inside the Parthenon. They were caught as they left the ancient temple by the guard on duty, but they had a stroke of luck. The sentry was from Crete, and one of the Englishmen was Patrick Leigh Fermor, who had fought alongside the Cretans during the resistance to Nazi occupation in World War II. On Crete, Fermor had mastered the local dialect and memorized a vast trove of folk songs and oral poetry.

The night suddenly took a festive turn. The men drank to Fermor. They drank to the nineteenth-century English poet Lord Byron, who had traveled to fight in the Greek War of Independence in the early 1820s. They drank to the eternal friendship between Britain and Greece.

Three years ago, when my wife and I moved to Athens so she could finish archaeological research for her PhD, I found myself thinking of Fermor’s escapade. I spoke much worse modern Greek—and drank far less—than Fermor. But I saw in him an archetype of a certain style of traveler, one defined by a deep curiosity about history and culture and a desire to gain lasting friendships and a broadened view of life. I’d outgrown the assumption of my younger self that it was normal to expect everyone to speak English while living abroad. To approximate some version of the Fermor ideal, it would be essential to learn modern Greek.

Fermor mastered modern Greek by living in remote caves with Cretan shepherds, speaking and hearing the language constantly. It helped that he also knew ancient Greek. He and other undercover agents were picked to work in Greece in part for this reason. The stakes for mastering the language were high. If Fermor’s fluency failed to convince when he posed as a local, he risked being imprisoned or shot.

Like Fermor, I knew ancient Greek; I’d spent years learning the language and reading ancient Greek philosophy in graduate school. Unlike his linguistic immersion in mountain caves, my modern Greek lessons happened in our Athens apartment over Zoom, lasting barely an hour a week. And the stakes were quite low. If I stumbled over grammar at our local fruit shop, the cashier would just laugh and switch into excellent English, a language now ubiquitous in much of the country after sixty years of globalization and the enormous growth of Greece’s tourism industry.

We arrived in Athens in the summer of 2020. The strict pandemic lockdown meant there were almost no tourists in the country. Then again, it wasn’t a great time to strike up conversations with anyone. Cafés, restaurants, archaeological sites, museums—almost everything was closed. For a while, you had to text a government number to leave your apartment. Luckily, long walks were still allowed.

As I wandered Athens during the first year of the pandemic, knowing the ancient language sometimes gave me a disorienting sense of compressed time, with the lofty and ancient suffusing the mundane and modern.

As I wandered Athens during the first year of the pandemic, knowing the ancient language sometimes gave me a disorienting sense of compressed time, with the lofty and ancient suffusing the mundane and modern. On the glass door of the mini-market near our apartment, the sign that told you to “push” used the same verb as Homer does in the Iliad when warriors “thrust” their spears.

At a carpet cleaners, the word for “cleaning” was essentially the same term Aristotle used in his theory of tragedy as catharsis—a “cleansing” of the soul. On cargo trucks and moving vans I saw the word that became the English “metaphor.” The ancient roots mean “to carry with.” Movers carry things, metaphors carry meanings from one domain to a new one.

Convenience stores and ancient songs of war, carpet cleaners and tragedy, moving trucks and metaphors: these millennia-spanning links somehow both enchanted the present and demythologized the past.

*

That first winter, a rare heavy snow fell on Athens, snapping branches, cloaking monuments, piling on cars and awnings. We took the day off and went for a walk around the city. Everyone else had the same idea. On the small hills near the Acropolis, people were sledding and skiing down the miniature slopes. Snowball battles raged between teenagers in the winding streets of the Plaka neighborhood, a zone of pastel-hued neoclassical architecture below the Acropolis. The whole downtown, usually jammed with traffic and tourists, now had neither.

It was a good day for Greek practice: everyone wanted to talk about the blizzard, as if to confirm it had really happened. The mood was a rare combination of elements: the joy of the snow, the release after pandemic confinement, but also the feeling that the downtown was not an overcrowded amusement park.

It was a feeling Fermor understood. He died in 2007, but by the 1960s he already saw the effects of globalization on Athens, where mass tourism threatened to replace the uniqueness of Greece with a generic nowhere aesthetic bleached of tradition. He found “many a delightful old tavern has become an alien nightmare of bastard folklore and bad wine”; after a remodel, one of his favorite haunts had “the vast and aseptic impersonality of an airport lounge.” It’s hard to immerse yourself in a new culture or language in an airport terminal.

The explosion of tourism is not just a problem for the language-learning goals of foreigners. Even many locals who make a living from tourism are disturbed by its growth. “We just want them to go home now,” a worker at a downtown store told The Guardian last year. As AirBnbs and multinationals spike rents and unsettle neighborhoods, life has become more precarious for many. “The city center is being transformed into an amusement park for tourists, like Las Vegas,” one small business owner told the newspaper Ekathimerini.

I recently met a Greek friend in Kypseli, a neighborhood near the center of the city that hasn’t yet been overrun by tourism. A painter who has had shows around Europe, he can still afford both an apartment and a nearby studio for his work. He doubted this would last much longer.

As we sat at an outdoor cafe in a square, I asked what he thought of tourism. “It’s a plague,” he said, calmly. He gestured at the charming, eclectic architecture all around us, “They’re going to want all this, too.”

*

Many travelers to Greece split into two broad types: the intellectual and the sensual. The poet Lord Byron and his traveling companion John Cam Hobhouse are good examples. Hobhouse was a seeker of knowledge, always eager to decipher inscriptions, trace references, and visit monuments. Byron was inclined to toss the guidebook, scrap the itinerary, and soak in the atmosphere. A friend recalled Byron saying: “John Cam’s dogged perseverance in pursuit of his hobby is to be envied; I have no hobby and no perseverance. I gazed at the stars and ruminated; took no notes, asked no questions.”

When I studied abroad in Athens as a twenty-year-old in 2005, there were still Byrons and Hobhouses. The former leapt from cliffs into perfect pockets of blue sea; they zipped around island coastlines on rented motorcycles; they drank heroic quantities of ouzo by driftwood bonfires on the beach. They took no notes, asked no questions. The latter lingered among vase paintings in the galleries of the National Archaeological Museum; they thrilled to distinguish different orders of capitals on temple columns; they crouched to decipher faded inscriptions chiseled into marble.

I floated between these groups. I liked the sensual spontaneity of the first, but saw how easily it became an empty hedonism. I admired the knowledge of the second, but resisted its drift toward pedantry. Years later, reading Fermor’s two classic travelogues about modern Greece, I realized what makes him so compelling: he embodied a hyperbolic form of both approaches. He somehow managed to combine sensual abandon—wine, feasting, swimming—with deep knowledge of the language, history, and culture of Greece.

For many early travelers to Greece, learning modern Greek would have seemed like a bizarre goal. They wanted only to commune with traces of the glorious ancients. European travelers sought vestiges of antiquity in the people, language, and cities of modern Greece; the 18th century poet Richard Polwhele, for instance, believed he saw “Homer’s head” in the face of “many an aged peasant.”

The modern country rarely matched their ideals. “The Greek tongue is very much decayed,” the scholar Edward Brerewood wrote in the seventeenth century. The nineteenth century English traveler Frederick Sylvester North Douglas felt that Corinth, “the seat of all that was splendid, beautiful, and happy,” was now “degraded to a wretched straggling village of two thousand Greeks.”

For many early travelers to Greece, learning modern Greek would have seemed like a bizarre goal. They wanted only to commune with traces of the glorious ancients.

This mix of reverence for Ancient Greece and condescension to its modern inhabitants had a paradoxical result: some classically educated Europeans felt “more” Greek than the actual modern Greeks and made this known by taking artifacts or leaving their mark on them. Wealthy visitors like Lord Elgin employed agents to hack the marble frieze from the Parthenon and ship the sculptures back to England between 1801 and 1812. An English magazine article from 1814 endorsed vandalism, declaring that “it was an introduction to the best company….To be a member of the ‘Athenian club,’ and to have scratched one’s name upon a fragment of the Parthenon.”

By the mid-twentieth century, writers like Lawrence Durrell and Henry Miller shifted from reverence for antiquity to a sensual evocation of the Greek landscape and a romanticized vision of modern Greeks. The prose is better, but Miller’s 1941 travelogue, The Colossus of Maroussi, resembles the countless blogs and websites that now present the Greeks as masters of the carefree art of Mediterranean living, in which clocks are a nuisance, the sea sparkles nearby, and there’s always another glass of wine to be savored with a smiling friend.

This vision has become the bedrock of the modern tourism industry. One Greek travel website gushes that a cooking class on the island of Santorini is hosted “in a traditional local’s home.” Another offers the chance to become “Mykonian For A Day.” Beside a blog post called “Live like a Greek: The Art of Slow Living,” praising relaxed Greek attitudes toward time, a pop-up window promises that any email queries will be answered within twenty-four hours. It’s the art of slow living—just not for the person who answers your email.

*

In my modern Greek lessons over Zoom, when my desire for expression outstripped my vocabulary, I would reach for an ancient Greek word and hope for the best. The result was something like an English speaker interspersing bursts of Shakespearean diction with the general level of a toddler (“Do you like coffee?” “Coffee yes, banisher of the slumberous.”) My teacher found this amusing, and sometimes comprehensible, but many people were confused by the strange contours of my knowledge. I’d stumble over a simple bit of grammar, only to rally with fantastically grand vocabulary.

Sometimes this created an instant rapport. After one taxi ride, my driver parked outside our apartment, shut off the meter, and lit a cigarette. He wanted to sit and keep talking. I’d mentioned that I studied ancient Greek, and he spent the drive developing a theory of the internet as a version of the cave in which a Cyclops imprisons Odysseus and his men in Homer’s Odyssey. The details were murky, and not only because of my imperfect Greek. But I got his gist: the internet was a realm of darkness in which we were locked by the cannibalistic giant of big tech, and we should escape. He cracked the window and exhaled a luxurious stream of smoke.

“What’s the ancient word for bread?”

I told him: ἄρτος.

“Exactly,” he nodded. “Like we have on bakeries.”

He directed a stream of smoke out the window.

“Homer knew lots of things,” he added, with a significant glance in the rearview mirror, and I began to suspect he believed Homer knew about the Internet.

My Greek teacher and I sometimes played a game in which she listened to me speak for a few minutes and then decided how she would identify me if we were strangers. For most of the first year, I sounded like what I was: an American. By the second year, on good days, she upgraded me to a Greek-American who heard the language a bit growing up, but maybe just from grandparents on summer visits. By our third year, I was a more plausible Greek-American, as if I’d actually heard the language more as a kid, though I was still short of being truly bilingual.

As I was struggling to gain the language skills of a linguistically neglected Greek-American, my teacher enjoyed highlighting the distance between cultures that language can expose. When she taught me the verb χαριζω, which has a dense cluster of meanings related to giving to others and is connected to an ancient word for joy, she smiled. “This must be strange for Americans—you don’t connect these things very often,” she said.

*

Each summer we traveled to a small village in the mountains of Crete, where my wife was on a team of archaeologists excavating an Iron Age settlement roughly 2800 years old. The modern village sits midway up the steep slope of a mountain, its small whitewashed houses rising in tiers above a valley of olive groves. The population swells slightly in the summer, but there are only a few hundred permanent residents. Many houses have been abandoned for decades, with green vines twisting over the crumbling stone walls.

The archaeologists stay in old houses throughout the village. Ours had a single area as kitchen and living room on the ground floo. In the basement, reached by descending a ladder, was a bedroom and a bathroom. The ceiling was a mesh of branches bisected by great gnarled beams from tree trunks.

We woke each morning marked by small red bites from fleas. To cook, we cranked open a canister of gas beneath the stove. One afternoon we met a woman who had grown up in the house, and she started recollecting her childhood, roughly half a century ago. Six children, the parents, and their livestock animals all shared the two rooms.

By last summer my modern Greek was finally good enough for more complex conversations. Most mornings, while my wife was excavating the ancient settlement, I sat with a coffee among old shepherds and farmers at a taverna in the village’s central square, chatting and listening. The world my Greek illuminated was often dark. The dogs chained on short metal leashes at the top of the village were guarding drug houses. The kids roaming the streets were avoiding their house because their father was drinking again and often violent. This was not the Greece sold with the “Live Like a Greek” mantra.

The second taverna in the square was locked in a feud with the first: the staff squabbled over parking spots and the boundary lines between tables and competed for customers. By midday, groups of tourists appeared on ATVs rented in the resort towns on the coast six miles away. I was speaking with a waiter at the first taverna one day when the growl of engines signaled the arrival of a batch of sunburned tourists. He walked a few steps toward them, but as they parked, the daughters of the second taverna’s owner encircled them, menus in hand, steering them toward open tables.

“Beer, wine, traditional food, everything you want,” the owner of the second taverna said in English, walking up behind the girls.

He walked back toward me and shook his head.

“You see how it is?” He asked me in Greek, tossing the menus on a table and lighting a cigarette.

Late one night, we heard frantic pounding on our door. On the street outside, the air was acrid. The sky was an eerie orange, with huge plumes of smoke banking and twisting. We grabbed our passports, dog, and shoes, and tried for several minutes to rouse our 90-something neighbor by banging on her door. We shouted a host of words for fire and flame, then headed for the edge of the village, away from the smoke.

We learned a few hours later that a fire had started just below the village on a grassy hillside. Firefighters and villagers had barely managed to extinguish the blaze just a few feet from town.

A few days later, a young man with a history of drug problems confessed to the police that he had started the fire. Various theories swirled through the village, but most people thought the owner of one taverna had paid the man to start the fire to intimidate the owner of the other. The hillside below the square was now charred and blackened, and the smell of smoke lingered for weeks.

The threat of real violence in the square, always implicit, now felt sharper. For the next few days the tourists, after parking their ATVs, would wander over to look at the burned slope. They had no idea they were lunching at the site of an arson attempt that nearly destroyed the village. As an undergraduate abroad in Greece, or even when I knew only ancient Greek, I would have been equally oblivious.

When I arrived, my ancient Greek would come to the rescue, however haphazard, of my modern Greek. Now it was just as common that I’d decipher a word in an ancient text by knowing its modern descendants.

By last summer, my wife had finished her PhD and accepted an academic job back in America. We were leaving just as I was becoming a more persuasive modern Greek speaker. My ancient Greek, meanwhile, had morphed far from the standard Erasmian pronunciations taught in western universities; it had the pointy vowels and conversational cadence of an Athens cafe, not a seminar room.

When I arrived, my ancient Greek would come to the rescue, however haphazard, of my modern Greek. Now it was just as common that I’d decipher a word in an ancient text by knowing its modern descendants. After three years in Greece, I occupied a murky intermediate zone, somewhere between Byron and Hobhouse, ancient and modern, outsider and local.

The night before we left the village this summer, our neighbor in her 90s stopped to talk outside our front door. She was alive when Fermor joined her parents’ generation in the resistance to the Nazi occupation. She told us about her family, and how life in the village used to be. It was early evening, the sun staining the steep hills of the valley above us, the heat of the day finally broken. At this hour, she said, the street used to be thronged with people.

Now it was all different. So many had moved away or died. It seemed quieter every year. I felt a sudden twinge: we too would be leaving soon. Most of the people who lived in the village were old, she said, and only one still came to check on her. Then she smiled and patted my wife’s arm. We were good neighbors, she said, because we spoke to her.

Nick Romeo

Nick Romeo covers policy and ideas for The New Yorker and teaches in the Graduate School of Journalism at the University of California, Berkeley. He has also written for The New York Times, The Washington Post, National Geographic, Rolling Stone, The Atlantic, and many other venues. His book The Alternative: How to Build a Just Economy, will be published in January, 2024.