The spare desert stirred the most luxuriant imagining; shadows and color bore meaning, light a deliriously languid ecstasy […] Often there would come to me mysteries more intriguing than any lucidity—how, for instance, in a place with few or no human beings, one could begin to see the worth of what it means to be human.

Article continues after advertisement–Ellen Meloy

*

The Anthropology of Turquoise is less a book to me than a river that has long run through walls of rock, excavating, capturing, carrying away all it encountered. Just why this river decided to flow into my life I can’t say, but I find peace in recounting the events that bind me to it and wonder if perhaps in reading about them you will find some too. Writing is not my profession. The act at once attracts and terrifies me. I’m a translator, and translators don’t like to hear their own voice. But this time I can’t hide behind the words of others, because the story of this book is also my own. What I’ve done for it, I’ve done for myself.

*

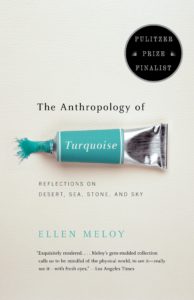

I was introduced to Ellen Meloy by a friend. Following our first encounter he recommended me a few collections of nature writing. He had sensed my fascination for the vast open spaces of the West and imagined I would enjoy reading the accounts of those who had experienced and loved those very spaces. Ellen appeared at the top of a list that included authors such as Barry Lopez, Camille Dungy, Annie Dillard and Rebecca Solnit. I picked up a copy of The Anthropology of Turquoise and for a couple months let it sit in the limbo that is my personal reading shelf.

At that time, my husband Leonardo and I had just founded Black Coffee and were traveling across Italy presenting our idea to booksellers. And so I began reading The Anthropology of Turquoise in front of Lake Como on a clear spring day. I was worn out from all the constant movement, and remember how the lush green of the surrounding forest and the turquoise water reinvigorated me, anchored me to the present, stabilized me. And in that state of vibrant calm, I found the serenity to dedicate time to myself. I could never have known that from that act of reading a wave would emanate powerful enough to carry me to the other side of the planet, to a part of the world where people long for water as if it were a precious gem.

That’s where Ellen Meloy began, 8,000 miles to the West of me, sitting on that shore on Lake Como. Her biography I would later find, had the same mixture of change and love that took me from a lonely translator’s desk to the shores of book publishing. Born in Pasadena, Meloy (née Ditzler) began her exploration of the desert in the arid California foothills, which she would later leave behind to follow her father on his travels as an airplane pilot for the federal government. She received a university degree in London, studied in Florence, Rome and Paris and for a time worked as an illustrator in Baltimore and San Francisco.

But the desert would soon reclaim her.

In 1979, after completing an Environmental Science degree at the University of Montana, she moved to the city of Helena and in 1985, in the Elkhorn Mountains, she and Mark Meloy were married. A few years later, Mark took a job as a ranger in the Desolation and Gray Canyon area of the Green River and the couple moved to Bluff, in Southern Utah. Seven seasons later Ellen published her first collection of essays, Raven’s Exile: A Season on the Green River, and from then until her death in 2004, from the desk in the home she and Mark built on the banks of the San Juan River, she never ceased to honor these places through her potent, lucid words.

What attracted her more than anything to this landscape was the paradoxical contrast between the vermilion red of the canyons and the turquoise skies that overlook the desert. In English the word turquoise means both the color—the middle ground between yellow and blue, a pulsating place of tension Ellen could never let go of—as well as the gemstone the desert conceals in its innards, “the burden of waters.” Turquoise, the stone the Indians have long revered and worn as an amulet to bring prosperity and good fortune.

In a Martian landscape of blazing stone and blond, windswept dunes, the sight of turquoise is an electric shock, reawakening the feeling of life, accelerating the heartbeat.“Turquoise. It is the stone of the desert. It is the color of yearning. […] It comes from arid, dusty, stripped-down, skinned-earth places. It occurs almost exclusively in the geography of ascetism, in broken lands of bare rock and infrequent green. Set against the palette of desolation, a piece of turquoise is like a hole open to the sky.”

In a Martian landscape of blazing stone and blond, windswept dunes, the sight of turquoise is an electric shock, reawakening the feeling of life, accelerating the heartbeat. In search of that shock, Ellen didn’t hesitate to venture into a world, as she defines it, “of beauty and violence.” Her deepest desire was to attain a sensory connection to the environment she had chosen to call home and in doing so chart a map of her own interior universe. For a long time she limited herself to observing, to paying attention to her own “neighbors,” the living things with whom she shared the land—the yucca and prickly pear, the lizards, ravens, red-tailed hawks, even the coyotes, bighorn sheep, mule deer—and had to learn to live alongside. Laying stretched out on the rocks she became one with the environment surrounding her, a creature of dust and sun whose sinuous folds sheltered a heart of turquoise.

“I no longer want to know the names of things. I do not care if I ran mute or if my tongue is useless for everything but the taste of salt. The verbal map is the wrong map. It is a labyrinth to false treasure. This toxic, wholly liquid place lies outside words but well within the realm of the sensual. The colors come forth for their own sheer ecstasy.”

Alone and disarmed, Ellen sought to understand the origin of this visceral attachment she felt towards these places that didn’t belong to her by birthright but that she nonetheless perceived as a part of her. She began to ask what clues the eye latched onto in order to determine that a given landscape was home (“How does vision, this tyrant of the senses, draw someone to a piece of earth? What do the eyes rest upon—mind disengaged, heart not—that combines senses and affection into homeland?”). In the silence she would understand it was the shapes and combination of colors that inspired in her that state of intoxication. (“Intoxication with color,” she writes, “sometimes subliminal, often fierce, may express itself as a profound attachment to landscape. It has been rightly said: Color is the First principle of Place.”) The sense of belonging one feels before a certain view, Ellen writes, does not require elaborate justification or a careful study of a family tree. Perhaps the issue is simpler: it is the colors that speak directly to our genealogy, reawakening in us an intimate connection with the landscape our ancestors sensed was most conducive to their own innate qualities and strengths.

This handful of words was enough to push me to publish The Anthropology of Turquoise. I became convinced that, in a society where far too often we value what is less relevant and find meaning when there isn’t any, many others like myself might need to be reassured of the wisdom of their own instincts. If even just once in your life you’ve felt you belonged somewhere other than where you were born, and were almost ashamed to feel this way because you didn’t know this place deeply, because it wasn’t yours and there was no pressure to make it feel as if it was, and if at a certain point, fully aware of condemning yourself to an eternal exile, you still chose to carve out for yourself a tiny corner in this place, then this book is also for you.

*

A few weeks after acquiring the publication rights to The Anthropology of Turquoise I received an email from Ellen’s younger brother Grant. Mark had called to let him know an Italian publisher was planning to put out the book, and his happiness at this thought pushed him to get in touch with me. He had been there while Ellen was writing, was physically present in the events described in the essays that make up the book, and in the absence of his sister he was offering to help me untangle knots and interpret passages. If you need me, I’m here, he wrote.

But a few years back, during a trip to Arizona, I came to know a small part of the American desert and since then I’ve never been the same. A weight fell from my heart.In the subsequent lines I would discover that “here” wasn’t only figurative: Grant, a retired teacher, engraving artist and historical researcher, was in Italy conducting research for a project he’d had in the works for years, and more precisely he was writing me from the San Giovanni Library in Pesaro. Florence has been my home for the last twelve years, but I was born in Pesaro, the city where my parents and sister still live. Do you think it would be possible to meet, get to know each other better and talk a little about Ellen? Grant asked at the end of his letter. I raised my gaze from the computer screen and for a few moments couldn’t move a muscle. I tend to not put too much stock in coincidences. Often they are merely mirages arising from a strong desire. But this was impossible to ignore.

To me The Anthropology of Turquoise had much to do with the concept of “home”: wherever I’ve lived—I must have changed at least fifteen houses in my life—I’ve always felt like I’m just passing through, an outsider. I’m no good at being still. But a few years back, during a trip to Arizona, I came to know a small part of the American desert and since then I’ve never been the same. A weight fell from my heart.

By the time Grant wrote me I had already decided to publish The Anthropology of Turquoise, because reading it had liberated me: with her words Ellen had granted me the right to feel what I was feeling. If I had found harmony in the American desert, perhaps this was more than mere suggestion. Sooner or later I will return, I kept telling myself. But that day, unexpectedly, the desert had reached out for me. A fissure had opened in the rock and with its long fingers had crossed the ocean. It didn’t want to be just a faraway place, a mirage. Through Ellen it was calling out to me.

I wrote to tell Grant I was ready to meet, and that the library he was sitting in was the same one I went to as a child to work on school projects, that the street it sits on is the same one where, twenty years earlier, I would walk arm in arm with my best friend every Saturday afternoon.

A couple weeks later we met in Florence and embraced like two long-separated old friends. It was the type of embrace I’ve shared with very few people in my life. The next few hours are like a flash of lightning in my memory. Sat in my kitchen drinking coffee, with a map of the American Southwest and my laptop open before us, we searched Bluff on Google Maps. Grant wanted to take me there, to the house Ellen had built with Mark in one of the most desolate parts of Utah. He wanted me to retrace her footsteps, to meet the people who were important to her, to understand for myself just what the desert can do to a person’s heart. He couldn’t have known that my own had already fallen prey to that enchantment. He wasn’t surprised to hear this when I told him. He didn’t want to know why his sister’s words had left such a deep imprint on me. He asked me only to meet, one year later, in Bluff, where we would find Mark.

The silence, the vastness and desolation of the terrain inspire a state of mute contemplation, a sense of self-removal from the frenzied world of human beings and elicit an acceptance of the ascetic life.At this we said goodbye, with an embrace that felt like a promise.

“For me the bond between self and place is not conscious—no truth will arrive that way—but entirely sensory.” A few months later I reread these words as Leonardo and I prepared to leave for the United States. We had had to clear everything out of our apartment for some restoration work that would soon be starting and hopefully completed while we were away. I remember waking at dawn on the morning of our departure. The apartment was immersed in a deep silence, the furniture lay covered in sheets of opaque plastic, the walls were bare. Light filtered in through the windows, tracing an alien landscape. Are you still my home? I said to no one.

We arrived in Bluff from Salt Lake City on September 30, having driven for miles through the land of the canyons, an inferno of rock that would rear up dizzyingly only to drop off a cliff’s edge, vanish into thin air, dissolve into a sea of sand before rising anew from the parched riverbeds that bring life to this ancient landscape, one orphaned by water. The kingdom of an omnipotent sun, a place capable of wavering even the steadiest minds, insinuating doubts sharp as knives. The silence, the vastness and desolation of the terrain inspire a state of mute contemplation, a sense of self-removal from the frenzied world of human beings and elicit an acceptance of the ascetic life. The Mormons know something about this, having chosen this as the land on which to build their church. But the desert is cruel to those who cross it as if it were simply a film set. The desert punishes those who believe they can tame it, shields itself from eyes that have already decided what to see. The desert could care less what it is you wish to see. The desert sees you.

The only directions I had for finding Mark’s house were the name of a state road (no house number) and a vague reference to its location being “right after Bluff” if you were coming from the North. Once we reached the small town, to avoid wandering aimlessly towards a potentially unhappy outcome, I did what I always do, which, depending on your point of view, could be called either laziness or wisdom: I asked for help. I went into a shop and asked the owner if he’d heard of Mark. He replied that yes, he knew him and that at a certain point I should have made a left onto a narrow, dirt road just after the stone slab with the town’s name etched into it.

Immediately I saw in my mind the area Google Maps had shown me in detail. I then glided down from above to street level, flew over the brushwood driveway and pulled into the yard. Back in the car, on the actual earth, we retraced our steps rapidly, and came on the house in minutes. Mark’s best friend Steve came out to meet me. He had come down from the state of Washington to meet Leonardo and me, and to join us for those days of exploration. Then Grant appeared in the doorway and behind him an imposing man with messy white hair and eyes like two slivers of sky. I already knew much about him because he appeared often in Ellen’s books – they were deeply in love—but once more it took an embrace to make me realize just who I had before me and what I represented to him. Mark was silent for a long time as he held me to his chest. “Thank you,” he then said. And it seemed to me not another single word existed in the world.

*

That night I couldn’t close my eyes: I was afraid to miss the dawn, the moment when the sun would dye pink the rocky ridge that rose right outside my window, beyond the field of rabbitbrush dotted with yellow flowers. Then dawn came and went and I emerged to find Mark and Grant waiting for me at the breakfast table along with a row of juicy cantaloupe slices Mark had procurred for the occasion.

We Europeans are accustomed to taking whatever it is we want, to do anything to obtain it, and I am no different.Together at the table we read through some of the passages from The Anthropology of Turquoise I had struggled to translate. I would hold my finger on the page and await their response, which would never arrive without some delay. Grant and Mark would trade silent looks, messages I couldn’t decipher. They would then hazard an interpretation, hesitant, wishing they could be more precise. At times they would simply grin. Poor you, they’d say, because Ellen was a rare breed, a sui generis naturalist (in this very book she writes: “A great deal of nature writing sounds like a cross between a chloroform stupor and a high mass”) equipped with an extremely particular sense of humor, one almost impossible to express in another language.

It was that morning, I believe, that they truly came to understand the weight of the task I’d taken on. And, as if to remedy this, from that point on they never stopped teaching (“this smooth, wind-polished rock is called slickrock, this dark patina is called desert varnish, these are Yucca elata seeds…”), showing me things (the room where Ellen wrote, her favorite cactus, the pictograms at Comb Ridge, Butler Wash, Cedar Mesa, Mule’s Ear, Procession Panel…) or introducing me to people. Out on the trails they would constantly bend down to gather stones, flowers, raven feathers—and one day even one of those rubber ducks Ellen would always find on the banks of the San Juan, escaped from the factory upriver and carried to the valley on the current—which they would place in my hands with almost religious solemnity. If at sunset I turned away from the canyons to speak with them, they would implore me to turn back around—“We are not the spectacle here.”

Everything you see and find must stay where you saw and found it, explained Mark, an expert on the territory and the people to inhabit it over the centuries. This was the hardest lesson to learn: leaving things as they were, resisting the temptation to make them my own. Can you imagine the feeling of finding an Indian arrowhead in perfect condition and not being able to slip it into your pocket? A fire bursts in your chest, threatens to burn you alive, the desire is so strong that for a moment nothing else matters. We Europeans are accustomed to taking whatever it is we want, to do anything to obtain it, and I am no different. Denied this satisfaction of possession, I had no choice but to observe, listen, touch, smell. I could no longer sleep. My skin was dry and dark, like when I was a child at the end of summer. I was all eyes, nose, ears, no mouth. A passage from The Anthropology of Turquoise resounded in my head:

Each of us possesses five fundamental, enthralling maps to the natural world: sight, touch, taste, hearing, smell. As we unravel the threads that bind us to nature, as denizens of data and artifice, amid crowds and clutter, we become miserly with these loyal and exquisite guides, we numb our sensory intelligence. This failure of attention will make orphans of us all.

On the third day Grant and Mark took us to the banks of the San Juan. They had organized a rafting trip down to Mexican Hat to help us forge a more intimate bond with the river that had meant so much to Ellen and her work. “The San Juan River flows by my home and is so familiar, it is more bloodstream than place,” she wrote.

For the first time in a long while I felt clear headed, in control of my own body and strangely at ease.We would be camping for two nights. On the Navajo side of the river. This was technically illegal, but Mark, a former ranger, had been doing it for years, and his lie to the ranger in charge, who had, as is customary, come to inspect our equipment before we dropped the raft in the water, came with a smile.

Those who know me know I’m a petite woman who inspires in others a sense of protection, and have been treated this way my entire life. But on the river I began to glimpse a different version of myself: Mark and Grant wouldn’t let me just sit there, they always gave me something to do and through this I discovered a strength I didn’t know I possessed. The more I walked, the more I wanted to walk. My feet were no longer my own. I would wait for hours, eyes fixed on a rock face, hoping to spot a desert bighorn, the animal to which Ellen had dedicated her life along with one of her most successful works, Eating Stone: Imagination and the Loss of the Wild. I carried backpacks and other bags taller than I was and at night slept soundly despite the deep, endless darkness that surrounded the tent. For the first time in a long while I felt clear headed, in control of my own body and strangely at ease.

One day we climbed to the top of a hill to reach an ancient Anasazi site, one of the area’s most beautiful and uncontaminated (the Anasazi are the ancient people who occupied the Colorado Plateau around the 10th-century BC, ancestors of the modern Hopi and Zuni tribes). The earth was strewn with metates and manos—tools used by the native peoples for grinding seeds—all perfectly preserved, and even though we’d walked far and were running out water, I continued to wander as if I’d fallen into a state of feverish delirium, tormented by the thought of literally crunching history under my feet. The sky was a panel of turquoise, the high sun had erased the outline of all things. With my finger I was gently brushing a metate, as smooth as velvet, when Mark came over to me. “I don’t know why I like them so much,” I remember telling him. “Maybe your own people once used them,” he replied, “perhaps you have Indian blood in your veins,” as if it were the most obvious thing in the world. And I knew it wasn’t possible, knew I had no Indian blood in my veins, but for days I’d had a knot in my heart that in that moment dissolved, and in silence I cried. Later, I understood my tears came from the sensation that what Mark had really meant was: If you enter with respect, this can be your home too.

“Home is something you earn,” wrote Ellen. “Home is like a religion. Sensibly you understand the need of it, yet not even sensible people can explain it.”

*

“After Ellen’s death I found myself wandering in the Goosenecks State Park,” recounted Liza, Ellen’s best friend and the owner of the Bluff trading post, on the eve of our departure. “I felt hopeless, I just couldn’t make sense of why she was no longer here. Then I remember I saw my first golden eagle of the season, which began to circle directly above me. I knew it was Ellen, come to tell me that everything would be fine. This morning too I saw my first golden eagle. And then you showed up.”

That evening Liza gifted me a turquoise ring and smiled from her doorstep before yelling out a Ciao, bella that still rings in my ears.

Every nature girl and boy should be prepared to defend the places they love. Otherwise we have not earned them.Treating nature as a pet or a therapist ends up little better than treating it as a slave. Kinship demands reciprocity. Every nature girl and boy should be prepared to defend the places they love. Otherwise we have not earned them. When we march in from the starry nights and dazzling rivers, we must argue on their behalf, pressure politicians and other moronic invertebrates to wean themselves from their unsightly addiction to corporate blubber and for once act in favor of things that matter, like air to breathe, water to drink, and space to roam. We must exalt the biocentric paradigm, speak for the creatures that have no voice, staunch the lunatic hemorrhage of wild lands from the face of the planet.

Ellen wrote these words in the essay “Tilano’s Jeans,” and until the day of her death defended the place she had come to love, earning herself the right to call it home. Will we have the courage to do the same?

__________________________________

From The Anthropology of Turquoise by Ellen Meloy, trans. Sara Reggiani. Used with the permission of Freeman’s. Copyright © 2020 by Sara Reggiana.