How an Architect’s Endless Pursuit of Artistic Perfection Drove Him To Despair

Charlotte Van den Broeck on the Italian Baroque Master, Francesco Borromini

When I saw a picture of the Church of San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane in Rome, I knew almost for certain that the brazen and sensuous façade, its concave and convex undulations, must have been designed by a restless spirit. A simple Google search confirmed my suspicion. The architect, baroque master Francesco Borromini, is thought to have suffered from a manic-depressive disorder. Combined with his obvious perfectionism, this must have been the generative force behind his large oeuvre of superhuman designs. But the creative ferment of his genius had a dark side: he went through pitch-black periods of utter dejection.

In a sense, Borromini’s entire career was dominated by that church, San Carlo, whose small footprint has given it the nickname San Carlino. Along with the adjacent monastery and sleeping quarters, it was Borromini’s first solo architectural commission—though anything but a routine job. The parcel of land on which the church was to be built was small and inconvenient: an asymmetrical corner plot at the intersection of Via del Quirinale and Via delle Quattro Fontane, at the very summit of the Quirinal Hill in Rome.

That same intersection contained four fountains placed by order of the pope, which had to be taken into account in designing the church. Borromini inserted San Carlino among all those pre-existing elements with such mastery that you might think the street, the fountains and the hill were all made to fit the church, and not the other way round.

His brilliant design brought him greatness and despair. Lack of money kept him from starting work on the façade until the end of his life.

The floor plan is complex and invites several different readings. The clearest interpretation may be as a diamond with elliptical sides, or more precisely as two equilateral triangles with one shared side, around which an oval can be drawn—a deformation of the traditional central plan, which can be pictured as a stretched Greek cross.

Tutto il suo sapere. Borromini was instructed to display all his knowledge and skill in the church. His brilliant design brought him greatness and despair. Lack of money kept him from starting work on the façade until the end of his life.

*

A few days before his suicide, some time in late July 1667, Francesco Borromini knocks the maquettes off his table in one furious, well-aimed sweep. The clay hits the floor with a dull crack, very different from the sound of the glass in the display cases when he shatters them and stamps on the skeletal frames, smashing and snapping the fragile woodwork underfoot, and before long the whole floor of his workshop is littered with splintered wood, cracked clay and shards of glass, all pocked with bits of red wax and drops of blood, and he overturns the many crates and boxes and hurls them across the room in a shower of antique medals, twelve compasses, shells, hundreds of shells, followed by rare, clattering metalwork, lamps and spoons, and then, inflamed by the ear-splitting rattle, he pulls the horse’s head off the wall and flings it at the large stuffed ostrich, which tumbles to the floor, taking down the eagle’s head, which rolls into a corner, and, as his destructive frenzy comes to a boil, he thrusts his hand between the shards of glass in the case, grabbing the snakeskins from the display and ripping them to pieces, first with his hands and then with his teeth, and with the torn skin still in his mouth—his insanity now at its peak—he pushes over the plaster bust of Seneca (leaving Michelangelo in place) and seizes with still greater violence on his book collection, which he pulls off the shelves spine by spine, one book after another hitting the ground with a bang that dislodges its backbone, the pages defenseless against his rage, crumpling and tearing as he charges like a roaring bull through the chaos to the far end of the room, where, as he stands at his drawing table, his madness draws back for a few pensive seconds of hesitation, and then he tears up his drawings after all, his blueprints, sketches and studies, his hundreds of papers, into thousands and thousands of pieces, confetti blowing around the room like snowflakes, mourning the massacre. Amid this paper snowfall a servant finds Borromini, close to calm, contemplative.

*

A few days before the destruction of his workshop, Borromini had lost his friend and admirer, the antiquarian Fioravante Martinelli, whose death appears to have been the proximate cause of his own suicide. Martinelli had planned to write a detailed monograph about the Church of Sant’Ivo alla Sapienza; Borromini had furnished him with his original drawings for the project. Maybe after Martinelli’s death Borromini had no more use for his drawings, and knew he could not keep his own demons at bay much longer.

But the destruction of his entire archive and his whole life’s work—was that necessary? And if it was necessary, wasn’t that enough? Did he wish he could bring down the stones themselves? In that last, dark episode of his life in architecture, Borromini, if he could have, might well have torn down his buildings with his own hands. The maker retains the right of destruction.

Various sources describe his difficult personality and volcanic temper. He clashed with his patrons more than once. It is said that Borromini could not tolerate any intervention in his work. To him, the architect’s artistic intention was sacred, and he would brook no compromise. His unflagging quest for perfection, which seemed so close at hand in his pure and intricate architectural forms, eventually drove him to despair. He was only one man—how could he set an unshakable era in motion?

*

Rome, late sixteenth to mid-seventeenth centuries. The city is one vast building site. The Reformation has divided Europe, and the Catholic Church is fighting back with its bombastic baroque campaign: dynamic forms and dramatic effects, designed to appeal to the inner world of emotion. Through art and architecture, the Church hopes to regain its place in the hearts of the people. Many buildings from this period reflect the formal principles of classicism, because they were begun in the Renaissance. But they were completed in the baroque style.

Take, for example, the iconic St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome. In Michelangelo’s original design, the floor plan was a Greek cross with a broad ambulatory. When the architect Carlo Maderno was commissioned to complete St. Peter’s in 1603, he added a nave and narthex on the west side, changing the Greek cross into a basilica plan. He also altered the design of the façade, making it genuinely outward-looking.

Half a century later, in the spirit of the baroque idea that perfection is expressed by rounded forms, Gian Lorenzo Bernini added impressive elliptical colonnades that frame the approach to the basilica, like motherly arms embracing the crowds of the faithful in St. Peter’s Square. In this sense, the colonnades’ design embodies the baroque agenda.

His unflagging quest for perfection, which seemed so close at hand in his pure and intricate architectural forms, eventually drove him to despair.

The flood of investment in the new building campaign brought many professional opportunities for architects and artists. The two contemporaries Gian Lorenzo Bernini and Francesco Borromini were both put to work on the site of St. Peter’s Basilica. Under the patronage of Pope Urban VIII, Bernini’s career skyrocketed.

After the death of Carlo Maderno in 1629, Bernini, who had recently turned thirty, was appointed director of the entire building project. He took on the job of coordinating the ornamentation and sculpture in the interior. Driven by his ambition and self-taught genius, Bernini made choices that maintain a human scale in the church interior. His magnificent creations include the well-known Baldacchino, the canopy over the tomb of Peter the apostle.

In the shadow of Bernini’s successes, Borromini carried out more modest assignments for St. Peter’s, such as building the base for Michelangelo’s Pietà and sculpting a vivacious but solitary cherub over the relief in the southwest corner. His skill and his powers of observation caught the attention of the chief architect, Maderno, who took an interest in the young Borromini and, in Maderno’s final years, became almost a father figure to him.

While Maderno’s death provided a stepping stone for Bernini, it left Borromini with a lifelong wound. Maderno’s influence would remain in Borromini’s thoughts to his dying day. Borromini’s suffering was all the worse because he believed that he, as Maderno’s protégé, should have been the one chosen to make his mentor’s vision for St. Peter’s Basilica a reality.

Here lies the germ of the enduring rivalry between the two future baroque masters. The feud between Bernini and Borromini was to become one of the best-known personal conflicts in the history of Western architecture. From that point on, their approaches to architecture branched in radically different directions. While Bernini was admired by the public for the dramatic simplicity of his compositions, Borromini took the experimental path, striving towards an extravagant complexity that met with resistance from the Church.

Bernini’s architecture combined conventional forms with familiar elements in a manner that was safe and showed some continuity with classicism. His lavish interiors lent his buildings real artistic unity. Borromini’s interiors, by contrast, were austere. He tended to use inexpensive materials, such as white stucco, and hardly any gold or marble. This emphasized the three-dimensional geometry of his designs, giving free rein to his complex patterns.

When Borromini was accused of desecrating the classical tradition, Bernini was, of course, among his most vocal detractors. After all, Bernini and his school believed architecture should reflect the proportions of the human body. Borromini’s work is a distortion of the body, a lusty carnival of curves. Yet his designs never fail to intrigue. Despite Rome’s reservations about Borromini’s experiments, everyone acknowledged that nothing similar could be found anywhere in the world.

*

The eye finds no rest. Straight ahead of me is the frivolous mayhem of San Carlino, with nothing but the street between us, and I am going under. A tireless outpouring of bulges and hollows runs across the exhaust-blackened façade. Pressure and counter-pressure in a high-intensity wrestling match. The façade of San Carlino is both firmly anchored and a jiggly pudding. The tilted tondo at the top, which serves as a pediment, seems to lean in for a better look at the passersby. Even the statues in the corners of the portal are on the move, one foot in front of the other, as if they might step out of the gable at any moment. The honking of traffic down the hill between the church and me mingles with the building’s frenetic motion. It stirs me up, as if the surging stones represent the very essence of pursuit, reaching out of their joints towards some greater union with all that moves.

For Borromini, this was no easy project to complete. Not until thirty years after the church was built, in 1665, did he obtain the funding to continue his work. The struggle took half his life, and he seems to have given it his whole being. It devoured him, this unfinished thing, an open wound that gaped throughout his career, even after his later successes. With uncompromising dedication, he spent the last two years of his life working on the façade. But his perfectionism also returned, blocking his way forward.

In this period, he was felled by a series of severe depressions. Maybe he had some presentiment of the historic influence of his creation and that was what sank his spirits. He saw something take shape beneath his fingers that could never be equaled. His San Carlino would go down in history as the icon of Roman baroque; no one would ever match that accomplishment, not even Borromini himself. You cannot win a fight with your own shadow. The thought of what comes afterwards is simply a void.

Inside the church, the outpouring continues. Above the niche of the main altar is the beginning of a dome in a cross-section, interrupted at the bottom by a triangle with curved sides—and as I struggle over this description, the very act of seeing resolves the formal complexity. The building is pure mathematics, so correct that it feels harmonious, light and perfectly natural. The columns draw the eyes of the visitors upwards, to the light. How much higher does the church seem than it really is, because of this heavenward motion? I find myself in a weightless space. To think that stone can be so spare, so light.

You cannot win a fight with your own shadow. The thought of what comes afterwards is simply a void.

Dizzied, I wander out of the church—not into the street outside but into the street in memory. I am visiting Rome for the first time again, a few years earlier in July 2013. Not alone, as I am now, but with my first love and our best friend. In this triangular configuration, we have been taking the train across Italy for three weeks; Rome is our last stop. For years we have been inseparable. We’ve just graduated and we’re completely broke; everything here is too expensive. We haven’t booked tickets in advance, of course. The line for the Vatican winds back and forth through Bernini’s whole colonnade. We spend those final days in Rome wandering aimlessly, straight past all the things we’d planned to see. The sense of traveling ends before our travels do.

Yes, we’re still moving through the scenery of our destination, but at the same time we are no longer really here, and it’s hot—no, it’s suffocating. A heat wave lingers over Europe this summer, and Rome is the focal point of the blazing sun, with temperatures above forty degrees Celsius. As I write this now I am seized in the same full-body stranglehold as then among the throngs of milling tourists, an unholy heat that chases the three of us out of the city center. Like exiles, we stagger up the Quirinal Hill, and in our craving for shade we go blindly past San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane. We simply do not see the church; it is just too hot. Around 100 meters farther on is the Giardino di Sant’ Andrea—a “relaxing escape from heat,” Tripadvisor calls it. We stay there all afternoon.

How could we have walked straight past the commanding spectacle of San Carlo? What did I see that day? The thick trunks of the trees in the garden, yes, and a view from that high place on the hill, of the city quivering in the intense midday light. The cover of the book our friend was reading: A Philosophy of Boredom, an essay by the Norwegian philosopher Lars Svendsen. And the book my boyfriend was reading? I don’t remember, but I can guess: a novel by Gabriel García Márquez.

And now I see what else I saw: the pigeon, scruffy and half dead, under the tree that shaded us. Her tail bitten off, an injured wing drooping from one side, one eye crusted with pus; my heart breaks; the boys read, soaking up the shade of the tree, sinking into the afternoon’s lethargy like Tityrus and Meliboeus, as if Virgil himself had dreamed up the two of them, there, lost in their books in the cool shade, and as long as they remain in that other realm, the realm of reading, I am the only one left to take pity on the half-dead pigeon. How can I make her better, find ways to fix her? I pour water into the cap of my bottle, crumble salty crisps near her beak; don’t touch it, the boys say, it’s probably sick. Of course it’s sad, but there’s nothing to be done.

Yet I am doing something: I am acting by not taking action. I don’t touch her. I watch. For almost two hours, I watch the pigeon suffer: Where is her tail? How did she end up with that damaged wing? Does the pigeon understand the pain she feels? Does the pigeon know she’s dying? Could she be dead already? Is there any water left? And now? Is she dead now? Is it my job to put her out of her misery?

As the afternoon ends, we move on from the Giardino di Sant’Andrea in search of aperitivi. I leave the pigeon and her suffering behind. In silence, I drink to her certain death. No way of knowing how many more hours she had to wait for it.

That night, in the attic where we’re staying, I can’t get to sleep. The room is just below the roof and the heat of the day is still oppressive. The three of us are sharing a double bed. The rota we’ve drawn up gives us each one night on the side closest to the fan; tonight, it’s my turn to be in the middle. One pair of legs feels familiar under the sheets; the other remains at a decent distance, on its side of the shared bed. In the middle of this triangle I lie, in near-mathematical harmony, at the fulcrum of the vital balance between my boyfriend and our best friend, nestled in the six years of intimacy that led to this night.

My God, it seems to encompass my whole life. I am barely twenty-two years old, and I haven’t the slightest sense of direction, I hardly even have any ambition to write, maybe that’s why I can’t sleep, why I can’t help thinking of the pigeon, and then of the Etruscan haruspices, who could read good fortune and ill in animal entrails. What signs of my future lay hidden in that raggedy bird? What would the Roman augurs have made of her hobbled attempts to fly? Is this the unthinkable end of our intimacy? Must it expire?

I get out of bed, out of memory, and back to the present, strolling away from San Carlo towards the Giardino di Sant’Andrea. It’s not hard even now, years later, to find that particular tree in the fenced garden, but there’s no point in sitting there now as I did then.

*

The Giardino di Sant’Andrea is the garden of Sant’Andrea al Quirinale, a church built by Bernini. It was erected at the same time as San Carlino, and the sites are less than 200 meters apart. The rivals had to suffer each other’s constant presence.

In Piazza Navona, Borromini worked on the church of Sant’Agnese, while Bernini, straight across the square, was carving the Fontana dei Quattro Fiumi out of travertine, a commission that would have gone to Borromini, had Bernini not charmed the pope’s sister-in-law with a model of his design cast in silver. When the pope laid eyes on the silver miniature fountain, he was delighted and straightaway gave the job to Bernini, who with Borromini so close by could not resist rubbing his victory in his competitor’s face and worked an insult into his design for the fountain. Over the basin, four river gods each look out in a different direction; the one facing the façade of Sant’Agnese covers his face with his hand, as if shielding his eyes from the sight of Borromini’s church.

Borromini made an ironic gesture of his own by giving Sant’Agnese two monumental towers, the same height as its dome. This recalled the most embarrassing blunder of Bernini’s career: the pair of bell towers he had built on either side of St. Peter’s, which soon showed cracks and were hurriedly demolished.

A perfectionist deserves a good enemy, preferably one a little more talented than he is, so that he can savor his victories.

Whose is bigger? In the middle of his fountain, Bernini placed a 16-meter-tall Egyptian obelisk, a match for Borromini’s towers. Boyish pranks. But they were serious.

*

A perfectionist deserves a good enemy, preferably one a little more talented than he is, so that he can savor his victories. The rivalry between the two architects must at first have driven them to new heights, but in the end it made Borromini a bitter man. In the light of his artistic beliefs, the public’s embrace of Bernini was incomprehensible and came to feel like a rejection of Borromini’s own work.

In the summer of 1667, Borromini’s nervous disorder came to a head. His high expectations of himself as he finished San Carlino, the death of his friend Martinelli, his envy of Bernini, his never-ending drive for perfection… In retrospect, these were all signs that he had been drifting towards a cliff edge for years. Yet it was not until July 27, when he smashed up his workshop in a fit of anger and tore up all his drawings, that the people in his life intervened. If he had been capable of destroying the place where his whole life converged, then he was surely capable of worse. His cabinet of curiosities, his extensive art collections and the tools of his profession—all these had been sacred to him. Instead of asserting his status the way most architects did, with a pompous residence, he had surrounded himself with eccentric objects, from art to junk, and used them to build his own universe, a place where his imagination could roam freely.

The deliberate destruction of his studio was a spiritual suicide. A few days later, he escaped his minder’s attention and from his arsenal—which included four swords, a halberd and a small handheld firearm—he selected a medium-sized saber on which to impale himself, so that his body could follow his spirit into oblivion.

The self-inflicted saber wounds did not kill him right away. He was patched up to the point where he could receive the final sacrament and make his will. Then Borromini died in solitude; he had never married. He left his property to a nephew, on the condition that he marry the niece of his mentor Carlo Maderno. After Borromini’s death, his body was laid to rest in his mentor Maderno’s tomb. At his own request, there was no inscription. A miserable last wish: the architect who begs for his name not to be immortalized in stone. With this act, Borromini distanced himself from his chosen material and thus made his obliteration complete.

Bernini outlived his rival by several years, spending his old age in complacent idleness. His son Domenico tells of Bernini’s daily visits to the Giardino di Sant’Andrea in his final years; there, under the foliage, with a view of Borromini’s San Carlino on one side and his own Sant’Andrea on the other, the elderly master felt a deep peace settle over him.”

_____________________________________

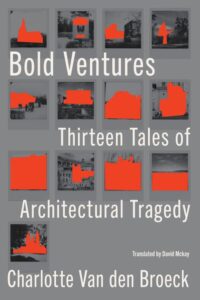

Excerpted and adapted from Bold Ventures: Thirteen Tales of Architectural Tragedy by Charlotte Van den Broeck, translated by David McKay. Copyright © 2022. Forthcoming from Other Press.

Charlotte Van den Broeck

Charlotte Van den Broeck is a Belgian author. Her first collection of poetry, Chameleon, was awarded the Herman de Coninck Debut Prize. For her second, Nachtroer, she received the triannual Paul Snoek Prize for the best collection of poetry in Dutch. Her poetry has been translated into German, French, Spanish, Afrikaans, Serbian, and English. Bold Ventures was a Dutch bestseller, won the Confituur Boekhandels Prize and the Dr. Wijnaendts Francken Prize, and was short-listed for the Boekenbon Literature Prize and the Jan Hanlo Essay Prize.