How an 18th-Century Cookbook Offers Glimpses of Jane Austen’s Domestic Life

Julienne Gehrer Takes a Closer Look at Martha Lloyd’s Household Book

Martha Lloyd’s Household Book is one of the few items we have from Jane Austen’s closest friend. As Martha was an integral part of Jane’s life, her recipe book is a highlight of the collection at Jane Austen’s House in Hampshire. It is fitting that the book resides at Chawton Cottage, a place both women called home. Much of what we know about Martha is through Jane’s letters and a few family reminiscences. But if we reread what has been written about Jane Austen we can catch glimpses of Martha Lloyd, who was often a figure in the background or just nearby. Included as a natural preface to Martha’s household book is an extensive biography of Martha Lloyd. Knowing more of Martha’s life leads us to a greater understanding of the deep friendship between Martha and Jane, a friendship that also included Jane’s sister Cassandra.

My first visit to Chawton Cottage in 1996 piqued my curiosity about the woman behind the manuscript cookbook. In more recent years I began connecting Martha’s recipes with the food references in Jane’s letters. With entries for toasted cheese, orange wine, pickled cucumbers, mead and many others, Martha captured much of what Jane enjoyed at the dinner table. Recipe contributions from Mrs. Austen, Captain Austen and Mrs. Lefroy affirmed Martha’s place within Jane’s inner circle. In fact, Martha lived over half her adult life within the closely knit Austen family. Many of the names in Martha’s book also appear in Jane’s letters. Some families—Fowle, Craven and Dundas—are actually more closely linked to Martha than to Jane.

*

Martha Lloyd in her own light

A full appreciation of Martha Lloyd’s Household Book begins with an introduction to its creator—the woman who befriended a young Jane Austen, shared a home with the famous author and later married into the Austen family. Like so much under the umbrella of Jane Austen studies, Martha’s existence has been defined by her proximity to the great novelist. But the life of Martha Lloyd can be better examined when pulled out from Jane Austen’s shadow and viewed in its own modest light. If Jane were writing Martha’s biography, she might begin with “Which of all her important nothings shall I tell you first?” Jane’s references to Martha involve the usual female topics of household details, apparel, balls, shopping and dining companions. There are no great headlines in Martha’s life story other than that she was Jane Austen’s closest friend. But Martha was also a loving daughter, sister, aunt—and eventually a wife and stepmother. As such, she had many claims on the affections of those around her.

We can compare Martha Lloyd with some of the secondary characters in Jane Austen’s novels. She supports the main plot and at times conveys critical information. Like Elizabeth Bennet’s close friend Charlotte Lucas, she seems content with her circumstances. Like Anne Elliot’s dear schoolmate Mrs. Smith, she is cheerful beyond expectation. Like Emma’s former governess Mrs. Weston, she gives helpful advice. Throughout her life, Martha’s actions demonstrated reason, duty, empathy, gratitude, generosity and kindness. As Jane wrote to Martha on November 29, 1812, “You are made for doing good, & have quite as great a turn for it I think as for physicking little Children.” In large and small matters, Martha was there for others.

*

Making connections to Jane Austen

Jane Austen readers could certainly be tempted to make instant connections between the famous author and Martha Lloyd’s Household Book. Is this the actual White Soup mentioned in Pride and Prejudice? Have we found the “Receipt” for “some excellent orange Wine” that Jane requested just months before her death? Of course, Jane never told us whether any of these recipes inspired her words, but since she and Martha shared several homes and similar experiences, it is natural to explore the possibilities.

There is nothing specific in Martha’s book to indicate Jane’s favorite foods. It would be astounding if a marginal note read “Jane gobbled this up!” similar to how she described herself “devouring some cold Souse.” There are no hints from the most worn or stained pages of Martha’s manuscript, but we can amuse ourselves by drawing many connections between the author’s works and these recipes. By simply paging through Martha’s household book, we can catch glimpses of Jane Austen living between the lines.

Pride and Prejudice is considered to be Jane Austen’s most famous novel, and its most memorable food reference comes from Mr. Bingley. He promises to host a ball at Netherfield, “and as soon as Nicholls has made white soup enough I shall send round my cards.” Although Jane could have sipped any version of the velvety, cream-based soup at the balls mentioned in her letters, Martha’s recipe is a likely candidate for the author’s favorite. But there was another White Soup recipe within the Austen family. The Knight Family Cookbook, compiled by Mr. Austen’s kinfolk, includes a variation of White Soup with vermicelli added. Readers will have to decide if they want to picture the spirited Lydia Bennet slurping up a few noodles in the presence of Bingley’s aloof friend Mr. Darcy.

Wise in culinary ways

Clearly Martha and Mrs. Austen were knowledgeable in ways to instruct a cook, but Jane also demonstrated her share of kitchen wisdom— perhaps learned in girlhood at her mother’s side. Despite Jane’s eventual eagerness to ease her mind from “the torments of rice puddings and apple dumplings” (January 7, 1807), her writing is seasoned with culinary references. Jane wrote to Cassandra on December 27, 1808 about some disappointing black butter that “proved not at all what it ought to be;—it was neither solid, nor entirely sweet. … It was made you know when we were absent.” Obviously Jane thought that she and her sister could have made better. But Jane could rely on Martha to oversee the making of “A Rice Pudding” using the recipe in her household book.

In another letter to Cassandra, Jane used her walk to the Alton butcher to specify her brother’s arrival time: “by the time that I had made the sumptuous provision of a neck of Mutton on the occasion, they drove into the Court—but lest you should not immediately recollect in how many hours a neck of Mutton may be certainly procured, I add that they came a little after twelve” (June 6, 1811). Jane helped with the marketing and knew how to select appropriate cuts of meat. A number of Martha’s recipes call for mutton, specifically the neck, breast meat, broth or suet.

Jane Austen’s novels are likewise sprinkled with culinary references. In Northanger Abbey, General Tilney eats heartily at his son’s table, being “little disconcerted by the melted butter’s being oiled.” Martha would have recognized the reference to the butter sauce and understood Hannah Glasse’s advice “to keep shaking your pan one way, for fear it should oil.” Martha’s recipe “To make Cabbage Pudding” finishes with “melted butter” sauce.

By simply paging through Martha’s household book, we can catch glimpses of Jane Austen living between the lines.

Nowhere is Jane’s culinary knowledge more apparent than in the detailed pork conversation in Emma. The heroine and Mr. Woodhouse discuss Emma’s gift of pork to the Bates household. In the span of three paragraphs, Jane includes fourteen examples of food seasonality, cooking terms and butcher’s cuts of meat. Most of these examples can be found in Martha’s recipe collection. Although Jane’s letters do not mention any butchering performed at Chawton Cottage, visitors can still see the livestock hoisting winch hanging from the bakehouse rafters. About the time Jane was completing Emma at the cottage, she wrote to niece Caroline: “Grandmama & Miss Lloyd will be by themselves, I do not exactly know what they will have for dinner, very likely some pork” (March 2, 1815). Martha collected six recipes of curing, pickling or preparing pork.

Peeking inside Chawton Cottage

Using Jane’s letters and Martha’s book, we can piece together typical days at the cottage. A beautiful spring afternoon could find Jane strolling through the orchard: “You cannot imagine—it is not in Human Nature to imagine what a nice walk we have round the Orchard … I hear today that an Apricot has been detected on one of the Trees” (May 31, 1811). Only two days earlier, she wrote of expecting “a great crop of Orleans plumbs—but not many greengages—on the standard scarcely any—three or four dozen perhaps against the wall.” All the ripened fruits from the cottage grounds would work well for Martha’s recipe “To preserve fruit of any kind.” Jane also described a good yield of gooseberries that would come in handy for Martha’s jam-like “Gooseberry Cheese” or “Green Gooseberry Wine.” But Jane noticed having “fewer Currants than I thought at first.—We must buy currants for our Wine” (June 6, 1811). Martha’s instructions “To Make Currant Wine” do not indicate the quantity of currants, but to yield each gallon of juice she would have to begin with several pounds of fruit.

Through Jane’s correspondence, we can watch the seasons unfold, from spring peas to summer vegetables, and eventually to autumn when bushels of apples could be transformed into a number of Martha’s dishes, including “A Baked Apple Pudding” and sweet “Apple Snow” with fruit and meringue whipped “for a full hour until it all looks like snow.” Jane did not hesitate to voice her opinion of their cook: “Her Cookery is at least tolerable;—her pastry is the only deficiency” (May 31, 1811). This was concerning because Jane felt that ‘Good apple pies are a considerable part of our domestic happiness” (October 17, 1815). Perhaps Martha helped the cook by sharing Mrs. Austen’s recipe for “Brised Crust” or Pâte Brisée (what we might call shortcrust or piecrust).

Jane Austen’s favorites

All the blooming fruit trees, shrubs and garden flowers around the cottage attracted bees from Cassandra’s hive. Whenever Jane was away, she was glad to get Cassandra’s reports of bee productivity: “I am happy to hear of the Honey.—I was thinking of it the other day” (September 23, 1813). Honey is the principal ingredient in mead, Jane’s favorite drink. Martha’s recipe “To Make Mead” calls for 4 pounds of honey for every gallon of water. Letters between the Austen sisters frequently mention the honey output and various stages of mead making: “Cook does not think the Mead in a State to be stopped down” (February 9, 1813). Ironically, Martha’s book does not include a recipe for her own favorite drink, spruce beer—but Jane mentioned it in Emma. The character Harriet Smith kept among her “Most precious treasures” a tiny pencil that Mr. Elton brought out “to make a memorandum in his pocket-book; it was about spruce beer.” Perhaps Jane had included the reference as a small homage to her dear friend.

Martha also saved a recipe for Jane’s beloved “Toasted Cheese.” The simple dish must have been known within the family as Jane’s favorite, because brother-in-law and likely suitor Edward Bridges arranged for it: “It is impossible to do justice to the hospitality of his attentions towards me; he made a point of ordering toasted cheese for supper entirely on my account” (August 27, 1805). We can imagine Martha thoughtfully planning the dish eight years later at Chawton Cottage, as Jane wrote Mansfield Park. Jane’s exhausted heroine Fanny Price took the first invitation to go to bed: “leaving all below in confusion and noise again, the boys begging for toasted cheese.”

__________________________________

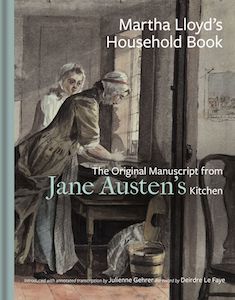

Excerpted from Martha Lloyd’s Household Book: The Original Manuscript from Jane Austen’s Kitchen, introduced with annotated transcription by Julienne Gehrer. Used with the permission of Bodleian Library Publishing. Copyright © 2021 by Julienne Gehrer.

Julienne Gehrer

Julienne Gehrer is an author, journalist, and food historian. She has served as board member of the Jane Austen Society of North America and she speaks frequently on Jane Austen and the long 18th century. She is the author of Dining with Jane Austen, working closely with historic manuscripts from Jane Austen’s House and Chawton House in Hampshire.