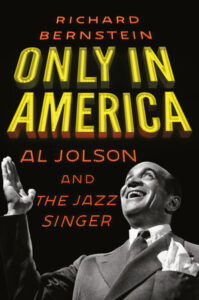

How American Jews Created a Place For Themselves in Show Business

Richard Bernstein on the Early Years of Mass Entertainment in the United States

There they were, Jewish titans of American show business, gathered at the Hillcrest Country Club in Los Angeles, itself an emblem of their success. The club was started in 1920 so Jews, who were barred from L.A.’s other clubs, would have one of their own, which is what Jews tended to do when they ran into the social antisemitism of America in the first half of the twentieth century. Within a few years, most of the Jews who made Hollywood were members—including Jack Warner, Samuel Goldwyn, Adolph Zucker, and Louis B. Mayer—even if they didn’t play golf.

George Jessel, the actor who played the lead role in the stage version of The Jazz Singer in 1926, went to the Hillcrest for the food and the company, both of which could be enjoyed at a large oak table, known as the Round Table, set in a corner of the dining room. That’s where the Jews who had made it big as singers, actors, and comedians gathered to eat, drink, smoke, and kibitz. Al Jolson was prominent among them. His friends George Burns and Groucho Marx were regulars. So were Eddie Cantor, Danny Kaye, Jack Benny, and Jessel himself, all of them huge stars of Broadway, the movies, and, later, television. Burns and Marx wrangled over who was funnier.

It seems likely that these men, in the privacy of their minds or perhaps out loud to each other, engaged in some amazed self-congratulation over how low they had started and how high they had risen. Certainly, one of the things that bound them together was an awareness of having achieved a degree of wealth and fame unimaginable to their immigrant parents, not to mention the families in the Pale of Settlement they’d left behind.

It seems likely that these men…engaged in some amazed self-congratulation over how low they had started and how high they had risen.They had all risen in similar fashion from similar origins along similar paths. Most of the Round Table regulars—Danny Kaye being the sole exception—were born in the last decade and a half of the nineteenth century, Jolson of course in eastern Europe, the rest in America, though just a few years after their parents’ immigration, so they could all speak Yiddish and were familiar with the ways of their ancestors. Except for Marx and Jessel, none of them were known by the family names they’d been born with.

George Burns, whose 272 episodes of The George Burns and Gracie Allen Show, first on radio, then on television, lasting from 1934 to 1958, made him one of the most beloved personalities in America, started out as Nathan Birnbaum, son of Eliezer Birnbaum and Hadassah Bluth, from a Polish shtetl called Kolbuszawa, then in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Eddie Cantor was born Isidore Itzkowitz in 1892; his parents were also Russian immigrants, both dead by the time Cantor, raised by a beloved grandmother, was two years old. Jack Benny, the son of Meyer Kubelsky and Emma Sachs from Poland and Lithuania, was named Benjamin Kubelsky at his birth in 1894. The youngster of the group, Danny Kaye, born in 1911, was formerly David Daniel Kaminsky, his parents from Dnipropetrovsk, then part of the Russian Empire, now in Ukraine, who emigrated to Brooklyn two years before he, their third son, arrived on the scene.

They also knew the poverty, or certainly the very modest circumstances, of Jewish immigration, and of American immigration in general, and of the people, especially African Americans, who were already here. These were the Ostjuden, the eastern Jews, poorer, coarser, less educated, more desperate than the mostly German Jews who’d arrived a generation before them, and their itineraries were rougher and more dangerous. The German Jews had no experience of the shtetl either in Europe or in the transplanted ghetto that was the Lower East Side in New York, where the Ostjuden were concentrated. The point for the German Jews was to continue climbing the ladder of American success, to eliminate the blatant antisemitism that, for example, limited their enrollment in the Ivy League (some did go there).

The Ostjuden sought to escape the grim urban quarters where most of the Jewish immigrants from eastern Europe landed. If escape wasn’t immediately possible, simple survival was the temporary goal, and there were many ways of achieving that, some of them unsavory. There were pimps and prostitutes among the Lower East Side Jews plying their trade on Allen Street, “with its dark and smelly houses and its rattling elevated train.”

There were socialist journalists and more radical revolutionaries; Abraham Cahan, the founder and editor of the Yiddish Forverts, in the former category, the firebrand Emma Goldman in the latter. The immigrant Jews were less inclined to outright criminality than some other immigrant groups, but there were plenty of petty thieves, pickpockets, fences, and bookies, and a few big-time gangsters, most notably Meyer Lansky and Bugsy Siegel, both of whom started their careers as thieves and pushcart extortionists on the Lower East Side, before they moved on to gangland murder in conjunction with Lucky Luciano and the mob.

Show business was an escape from the soul-destroying weariness of the metal workshops, shirtwaist sweatshops, cigar sheds, pushcarts, and small retail establishments where most of the first generation of immigrants eked out their daily bread. That was where the Round Table stalwarts came from, the subculture of street performance, vaudeville, and burlesque, the saloons and restaurants and beer parlors with their singing waiters and waitresses, the street corners where they busked for nickels and dimes, the flophouses or park benches where they sometimes spent the night, dreaming of making it big, which, needless to say, most of them didn’t.

Those who did make it, like the fellows of the Hillcrest Round Table, were the talented few, finding success because of the rise of what the German critic Theodor Adorno called the culture industry, the distracting popular entertainments of the urban working class, with their simple themes, sentimentality, spoof, and slapstick. This culture gave birth to music halls, nickelodeons, the vaudeville and burlesque houses, then radio, the movies, and finally television. The knights of the Hillcrest Round Table were lucky to be in a country that, having taken in millions of huddling masses from eastern and southern Europe, was ready for mass amusement and didn’t care much about who provided it, or where they came from, or even, at least to some nascent extent, what their color was.

Sophie Tucker, born Sofiya Kalish in Russia in 1886, sang for tips at the restaurant her parents owned in Hartford, Connecticut. “I would stand in the narrow space by the door and sing with all the drama I could put into it,” she said later. “At the end of the last chorus, between me and the onions, there wasn’t a dry eye in the place.” She eloped with a beer cart driver named Louis Tuck, went with him to New York, and by 1909 was singing at the famed Ziegfeld Follies, where she was discovered by William Morris, the founder of the William Morris talent agency (born Zelman Moses in 1873 of German Jewish parents who immigrated in 1882).

The knights of the Hillcrest Round Table were lucky to be in a country that…was ready for mass amusement and didn’t care much about who provided it.Sophie Tucker was “the last of the Red-Hot mamas.” She was fat, which she turned to her advantage with hit songs like “Nobody Loves a Fat Girl but Oh How a Fat Girl Can Love.” Fanny Brice, who inspired the musical and movie Funny Girl, was Fania Borach at her birth in New York in 1891; she dropped out of school to work in a burlesque review, and, like Sophie Tucker, ended up for a few years at the Ziegfeld Follies.

Dropping out of school was a common element in these biographies, as was singing for small change at ages so young as to be shocking by today’s standards. When he was just seven years old, Nathan Birnbaum worked making syrup in a Lower East Side candy store, where he used to practice harmony with fellow child workers. This led to something called the PeeWee Quartet, which performed on ferries and in neighborhood talent shows. “We’d put hats down for donations,” Birnbaum, a.k.a. George Burns, said years later when he was one of the country’s most recognizable television comedians. “Sometimes the customers threw something in the hats. Sometimes they took something out of the hats. Sometimes they took the hats.”

Julius “Groucho” Marx, whose parents were German Jewish immigrants, lived above a butcher shop on East Seventy-eighth Street in New York. At a very early age he had decided he wanted to become a doctor, but there was no money to send him to medical school. Instead, with the encouragement of his mother, he became a boy singer when he was twelve. When he was fifteen, he performed in a theater in the municipal amusement park of Grand Rapids, Michigan.

Cantor, the orphan, was perhaps the most closely acquainted with dire poverty among the later Hillcrest crowd. He was raised in a cramped, miserable basement flat on the Lower East Side by his grandmother, who had come to New York when she was already sixty, understanding not a word of English, eking out a precarious living as a shadchen, a matchmaker. “We had to laugh to keep from crying, there was such poverty, such misery and disease,” Cantor would write years later. “All the things that weren’t good, we had.”

__________________________________

From Only in America: Al Jolson and the Jazz Singer by Richard Bernstein. Copyright © 2024. Available from Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.