I’m not sure when the blind pencil vendor entered my consciousness as a stock character in the urban landscape. All I know is that he (he seems always to be a he) has been jabbing my blind sensibilities for a long time. I do, however, remember exactly when I first encountered a blind writer identifying with him. That was in the 1999 memoir, Slackjaw, by Jim Knipfel—who is the author of many books of fiction and nonfiction, and who I and other like-minded “blindos” (blind plus weirdo) consider the patron saint of blind punks.

On the eve of Knipfel’s blind-man training, someone at work asked him “what my trainers would do to me.”

Knipfel’s answer was: “First thing, I imagine… is they’re going to give me a tin cup full of pencils and station me on the corner of Forty-seventh and Fifth, just to see how much money I can make.”

Another friend pushed the idea further. “You know what you do? You take one of those pencils, see, and jab it into people’s eyes when they stop, and say, ‘Ha! Now you can go sell pencils, too!'”

This passage made me giggle when I read it years ago, and it made me giggle again when I reread it a few weeks ago. It was the first thing I thought of when I discovered a black and white photo of a blind pencil vendor in the New York Public Library.

As a blind person who wrote a book mobilized against ocularcentrism, I was as shocked as anyone to suddenly find one day that I had become obsessed with photography—or, rather, the obsession sighted photographers have with blind subjects. And so it was that I found myself researching the many anonymous blind faces in the vast photography collection of NYPL’s Wallach Division. This is how I discovered Walter Silver’s black and white photograph of a blind pencil vendor taken in the 1950s in New York City.

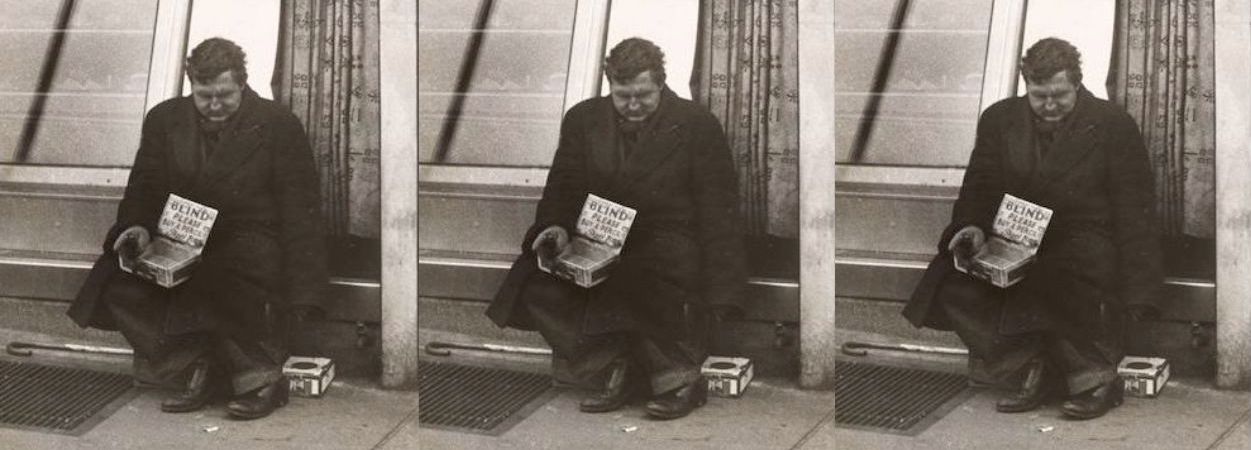

As a blind person who wrote a book mobilized against ocularcentrism, I was as shocked as anyone to suddenly find one day that I had become obsessed with photography.Silver’s blind pencil vendor features a man in a heavy coat sitting on the ledge of what appears to be a department store window. The man holds pencils in one hand and a sign written on the lid of the box that he’s holding on his lap with the words: “Blind” in big letters, and in smaller print: “Please buy a pencil. Thank you.”

After having both sighted humans and AI describe this photo to me, I decided to learn what some blind writer friends thought—I’m lucky enough to have a few very good ones! Of course, I started with Knipfel. I emailed him a description of Silver’s photo, and asked him a bunch of questions that basically boiled down to: why does the blind pencil vendor continue to resonate? Is it, like, related to low expectations? Both the low expectations most sighted people have for blind people and, more vexing still, the low expectations we newly blinded people have for ourselves?

Photo by Walter Silver, from the NYPL Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs.

Photo by Walter Silver, from the NYPL Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs.

“Yes, there’s certainly that perception that the blind are so pitiable and pathetic the only way we can make what even approaches a living is to sell pencils on street corners,” he agreed. But he noted there was something more going on. “Even though they were once a commonplace and very real phenomenon, generations after actual blind pencil salesman vanished the image remained… it became a cultural trope. The tin pencil cup was as much a signifier of blindness as a cane or dark glasses.”

One might suppose that signifier has already lost its teeth for younger generations, because, as Knipfel pointed out, “images of the blind as anything but noble and empowered are being scrubbed away.”

Yet I find the trope of the blind pencil vendor (or “BPV”) persists in depictions of blind people and in how we are treated by the sighted. The blind pencil vendor may be a thing of the past, but his presentation of blindness feels indelible. I’m nothing like him, and yet I’m mistaken for him, or, at least, something like him.

*

The blind pencil vendor was already an old story in 1890, when journalist/reformer Jacob Riis went into Lower East Side tenements with a camera and the newly discovered flash powder that allowed him to take pictures in dark places, and came out with How the Other Half Lives, a book that exposed the extreme poverty of many New Yorkers. For Riis a hundred and thirty some-odd years ago and for many of us today, the line between blind beggar and blind pencil vendor appears blurry at best.

“The blind beggar alone is winked at in New York’s streets,” wrote Riis, “because the authorities do not know what else to do with him… The annual pittance of thirty or forty dollars which he receives from the city serves to keep his landlord in good humor; for the rest his misfortune and his thin disguise of selling pencils on the street corners must provide.”

The blind pencil vendor is not really selling anything. It is a pretext for begging. A shabby disguise which fools no one. Silver’s photo clues us in to that fact: his sign announces no price; there is no sense that he will be making change for anyone. There is only the ask: “Please buy a pencil.”

I emailed Georgina Kleege, author of many books including More Than Meets the Eye: What Blindness Brings to Art, to ask her thoughts on the blind pencil vendor and why, despite (or because of?) his pitiful appearance, he feels like an easy joke.

“It must have something to do with the low value of the pencils,” she replied. “Why not sell something worth more, with more profit? Also I guess there’s the joke that he won’t know how much or how little money people are putting in his box.”

I might add: or, if people are taking money out of his box. It is not the first thing my “sighted informants” (thanks to Kleege for that term!) notice, but, there is a box to the left of the man that has a hole cut out of it. He appears to be dropping his money into that more secure place. This explains why he holds his pencils, and an empty box.

Most sighted informants find the stuff surrounding the blind pencil vendor quite eye-catching—to use a favorite sighted-people expression. To be sure, it’s a dynamic photo. On the other side of the window behind him stands a woman wearing a cloche hat, and the gathered curtains are patterned with a design that reminded one informant a little bit of Paul Klee. Most striking is the stack of newspapers bundled neatly in front of the next window over.

There’s all this interesting visible stuff surrounding the poor fellow that he doesn’t know about. It speaks to the sort of thing sighted people say to me often: It’s so sad you can’t see… the sky, this dress, how pretty you are (that was when I was younger), the spectacular fall foliage, etc.

But sighties also hit me with the opposite: it’s good you can’t see: that rat, how messy my house is, this horror or that. There seems to be an innocence attached to not-seeing that gets hung around the necks of we the blind.

The innocent ignorance of the blind is no more starkly put than in Kate Chopin’s 1897 short story “The Blind Man,” which briefly follows the ramblings of a door-to-door pencil vendor whose ignorance causes him to suffer many small discomforts but saves him from the final catastrophe. When we meet him in the heat of the day, he is walking on the sunny side of the street while everyone else is on the other side with its “trees that threw a thick and pleasant shade….But the man did not know, for he was blind, and moreover he was stupid.”

Chopin’s blind man is stupid because he does not remove his vest in the heat and trails the curb with his foot, apparently unaware that a cane (or stick) would be very useful in detecting obstacles and level changes. In other words, he is not very good at being blind.

And yet, it seems his ineptitude shields him from, first, noticing he’s almost been struck by a trolley car—which the reader/viewer is made, for an alarming moment, to believe happened. And second, continues on his way without noticing the death in his wake and the subsequent Horror “when the multitude recognized in the dead and mangled figure one of the wealthiest, most useful and most influential men of the town.”

I can’t help but notice that, in our cultural imagination, the blind pencil vendor/beggar seems always to be a man. Perhaps this is a kind of ironic inversion of the ancient blind poet/prophet (Homer/Tiresias). Perhaps too, the solo itinerant nature of the biz excludes women, who have traditionally been placed behind walls, while the blind seem always to be wandering outside them.

Andrew Leland, author of The Country of the Blind, reminded me of Chopin’s story (I had repressed it) when I hit him with my blind pencil vendor email query. He also gave me a delightfully sharp reading of it and the handy abbreviation. “The BPV is here a ridiculous, tragic, pathetic figure,” Leland replied, “but Magoo-like, he bumbles past any real harm.”

Mister Magoo is the blind cartoon character of the mid-twentieth century who traveled the most harrowing paths, never seeing (or experiencing) any of the dangers. Leland continued: “It is as though in his forsaken state, god spares him the worst accidents. He sells no pencils, but he somehow survives, hungry and bedraggled, anyway. He has no subjectivity—too stupid for that. He is all surface, pure emblem of ignorance.”

Unlike Silver’s BPV, Chopin’s does not carry a sign. He is the sign, a metaphor, a symbol less for the blind than for the presumably sighted consumer.Unlike Silver’s BPV, Chopin’s does not carry a sign. He is the sign, a metaphor, a symbol less for the blind than for the presumably sighted consumer. The Blind Man’s inconsequence is reinforced by the worthlessness of the thing he sells. Chopin underlines this worthlessness when she reveals that someone “who had finally grown tired of having him hanging around had equipped him with this box of pencils.” And, as far as we know, he never sells a single one: “the man or maid who answered the bell needed no pencil, nor could they be induced to disturb the mistress of the house about so small a thing.”

What’s most pitiful is how hard he’s working to sell something nobody wants or needs. It seems like, across the decades, “a pencil is the most trifling of goods for sale,” as Leland put it in his email.

When I mention this to one of my sighted informants, he said, “Pencils are great! I love pencils. We should go to that pencil store I told you about, get a photo of you in there!”

That particular informant is my sighted partner, Alabaster Rhumb. Pencil enthusiast. He is not alone. At Graphite Confidential, a website that chronicles “American history, one pencil at a time,” I read a brief article about how a blind organization reclaimed the BPV with images of blind children urging “mayors, socialites and everyday New Yorkers” to buy pencils stamped with “To Aid N.Y. Guild For The Jewish Blind.”

*

Stephen Kuusisto (author of Planet of the Blind and many other books of poetry and prose) finds the sign of the BPV to be a kind of stand-in for autobiography—or perhaps a barrier to it. “His appearance on the ordinary street is founded on the principle of auto-graphein,” writes Kuusisto in a lyric essay that accompanies his poem, ‘To the Pencil Seller.” “Surely he cannot write his life?” thinks the sighted passersby. “We shall buy his pencils.’

There’s something particularly degrading about the blind pencil vendor. He is selling cheap items, but more specifically, these are cheap inaccessible items. A sighted person fallen on hard times might take that hair’s-breath step up from panhandling to selling pencils, but he could—should he fail to sell them all—use one to make a note. A list perhaps of other, more lucrative, career paths. But the blind man can make no use of the pencil–except as a weapon à la Shakespeare’s archvillain in King Lear: “Out vile jelly!”

Kuusisto is provoked, ‘after long deliberation,” to write a poem in which the BPV talks back, with mystery and eloquence:

The blind man is amaranth, a man-word of sorts,

A word that will be mistaken on earth.

Still I

Saluted the closed world

Without its consent,

Cross the water of streets

And raised a sign

Unreadable as the moon.

Yes. We are human-made-word in the eyes of so many sighted. We are inscribed with meaning: blind poet/prophet, blind saint, blind beggar….And this amaranth, life-giving sacred grain, symbol of immortality. Hence death. With its red-petaled flowers that never fade. We are inscribed BPV and I, with letters we are presumably not able to read, letters that stretch from ancient times to now.

*

The endurance of the trope was made apparent to me one day on the New York City subway. I was sitting on the N Train with my guide dog, heading to NYU from Astoria. A man came up to me and was confused when he found that the lid of my Dunkin Donuts coffee was in place. Nowhere to shove his dollar. “Oh,” he said. “I thought….Here’s a dollar.”

“Um, what?” I was baffled. Then I wasn’t. All I could do to deflect the insult was laugh in his face.

The confusion many sighted people show upon learning that I use the very same iPhones and computers they do reveals, time and time again, how alien we seem to them.In The Metanarrative of Blindness, Disability Studies professor David Bolt describes an eerily similar experience. While waiting for his friend outside of a bar, a stranger tried to hand Bolt something. Thinking it was an inaccessible flyer of some kind, he did not put his hand up to accept—his “standard little expression of protest.” The man “seemed perplexed,” and paused “before asking if I was not collecting for the blind. At that point, though not in a can or a hat, a proverbial penny dropped for us both.”

When we are mistaken for blind beggars, it’s hard not to feel like our presence in the sighted world is being “implicitly explained by a cultural construct,” concludes Bolt.

To be sure, things have changed rapidly since the BPV haunted our streets. The digital era has a lot to do with this. We have access to books and information and tools of communication previous blind generations could not have imagined.

Yet attitudes towards blindness have not changed much since the days of Riis and Chopin. The confusion many sighted people show upon learning that I use the very same iPhones and computers they do—just tricked out with text-to-speech and a Braille display—reveals, time and time again, how alien we seem to them. Many sighted people ‘assume that blind people were just dropped out of the sky without any prior knowledge of the environment,” as Kleege put it. Such people are startled to find us in their midst.

After a Brooklyn barbecue last summer, I heard from the host that when my blind friend, I, and our sighted partners left, someone who didn’t know us said with surprise, “How do you know not just one but two blind people?”

This otherwise educated and hip human still fancies us as the other half, sitting on the margins of civilization with a tin cup, a sign, and some old-school (if sometimes fetishized) and inaccessible writing implements.

Enter the stock character riddling the blind landscape. They are the ignorant sighted person who remains blissfully, stubbornly unaware of the fact that such remarks make us want to poke them in the eye. But the accessible computer is mightier than the sharpened pencil. I content myself, with this brief sketch, in the hopes that they will recognize themselves, reach deep into their pockets, and produce change.